Htay Htay Win tracks down memories of her jockey grandfather, Thein Pe of the Rangoon Turf Club.

Passing through Moe Kaung Street and going further south towards Tamwe in Rangoon, one may notice an immense compound by the side of the road, the only residents a patch of unattended trees and bushes. Apart from some scanty signage reading “sports and physical department” here and there on one of its old brick walls, along an alley, one may wonder why it has been in a state of near abandonment for decades, despite the prime real estate location.

Many know of this compound simply as “Kyaikkassan” grounds (probably a Mon name) but the name of the road in front of it, East Horse Race Course road, has tell-tale signs of another story. In Rangoon’s glorious heydays of the past as a British colony, this place was known as the “Horse Race Course” or the “Turf Club.”

It was a place where the elites of Rangoon would meet every weekend to socialize, and enjoy the sports that had been imported by the colonial British since the early 20th century. Horse racing is undoubtedly one of the characteristic trademarks of the wealthy and bourgeois echelons of society everywhere, and it is fascinating to imagine what Rangoon looked like in those days. Before WWll spread to Burma, wealthy people of Rangoon, as part of their rich men’s luxuries, would also own horses and hire professional jockeys to ride at the races.

My connection to the Turf Club and this now forgotten patch of land extends through my maternal grandfather Thein Pe. His story began in 1900 in Dar Pein, a quiet little town near Rangoon beside the railroad to Mawlamyine (Moulmein). As a boy who grew up in the countryside, equestrian skills were not new to him. After his father died, when Thein Pe was in his early teens, his mother’s second marriage forced him to leave his native home with hopes of seeking future prospects in the big city.

Arriving in Rangoon, the young Thein Pe crossed paths with the son of Lim Chin Tsong, a Burmese-Chinese business tycoon, and was fortunate to become his best friend. If it were not for this very timely encounter, the life of Thein Pe would have been much different. Lim Chin Tsong’s father, an English-educated man from the prestigious St. Paul’s school in Rangoon, was kind enough to treat his son’s friend at an equal length. The otherwise homeless Thein Pe was invited to move into their lavish residence on Kokkine, at the edge of Golden Valley, just next to Kabaraye Pagoda road. This place is a landmark relic of the city known as the Chin Tsong Palace, elaborately built upon a massive rock mound that is only accessible by crossing a stone bridge that traverses a steep ditch and a small flowing stream that extends from the arms of Golden Valley. The Palace hosted several distinguished guests, including even the French Statesman Georges Clemenceau during his visit to Burma in 1920.

Coincidentally for the young Thein Pe, Lim Chin Tsong had come to own the Rangoon Turf Club soon after the end of WWI. As a talented rider, the young man from Dar Pein thus had the chance to practice his equestrian skills professionally as a gentleman jockey, and went on to earn some social recognition among the elite class of Rangoon.

While living in the palace, Thein Pe knew of all the little nooks and corners, but one day, to his surprise, he discovered that the tycoon was running a counterfeit money production that was taking place right under his floor. He quickly packed his small belongings and left the palace at once.

His decision again came at very coincidental time, for fate soon turned for the worse when the Chin Tsong family fell into jeopardy some years after the completion of the construction of the Chin Tsong Palace, and the tycoon lost his business to the ruling British empire. Within a few years, the entire family fell from riches to rags, and endured heavy debts. The tycoon himself was found dead in his sleep not long afterwards, and the circumstances surrounding his death were told to be mysterious, with rumors of the family running away from their financial demise.

My grandfather’s decision to flee stemmed from him being a very pious man, and he lived his life strictly according to the moral ethics of Buddhist doctrines until his last breath. Despite his success at the racetracks, he considered himself purely a sportsman and repeatedly spoke of his loathing of what he considered dirty gambling money, even though most of it was probably due to bets being placed on him from the spectators.

The runaway young man from the Chin Tsong palace was most welcomed by another rich man of Rangoon, not Chinese this time, but an Indian man by the name of Mappara. Thein Pe’s introduction to the elite social circle during his time with the Chin Tsong family had led him to this man, who also happened to be another tycoon and lived in a beautiful hill-top mansion with a bell-shaped hall, decorated with colorful mosaics, where the Embassy of Singapore stands today in Shwegondaing.

Soon after at Mappara’s, Thein Pe started earning enough to stand on his own as a young professional jockey, and would meet the woman of his life and settle down. He was exceptional in his league and would win almost every race, but according to his high moral ethics he would never bet or gamble on his favorite sport. Instead, he saved up his generous salary and invested in more horses, in addition to his other passion, which was to buy the newest model car each year. Thein Pe even went through a time when he was recognized by the British government as one of the elite super taxpayers. In his days, Thein Pe was the equivalent of a modern-day football player or other star athlete.

Up until the start of WWII, his collection of what he recounted were 80 horses throughout his career included his favorite thoroughbreds from England, and select breeds from Meiktila and Pakkoku in central Burma. His stable sat atop a hill near Shwegondaing, on the present-day Excel Tower and Golden Hill site, and reddish, tamarind-seed colored breeds were for him, the crème de la crème. It must have been a very costly hobby in the late 1920s and early 1930s when a race-horse was priced at about 3000 kyats, while a gram of gold went for 13 kyats. He was avidly passionate about his horses, and would treat them like family members, patiently brushing and wiping the sweat off his horses and talking to them before riding.

He often spoke of a mutual relationship, a bond, between him and the horse. He used to tell us proudly how he won the races: “Although I have a whip in my hands as part of my jockey attire, I would never hit the horse I’m riding to win the race. Instead, I would just whisper into the ears some nice and encouraging words like ‘go my big son… go’”. His wife and my grandmother, would place his racing whip at the small Buddhist altar at home. In the year 1923, he was invited as the guest of honor to a gala dinner at the Governor’s Palace for winning the Prince of Wales’ Cup in addition to six other cups in the same year, all in a row. This career highlight set him apart as a famous jockey amongst others. To distinguish him from another homonym of the same name in jockey world, he was also called Thein Pe-2.

When the Second World War’s fire engulfed Burma, Thein Pe and his family had to abandon Rangoon for a remote village, fleeing from the aerial bombs that fell over the city. He would never see his beloved horses again.

I remember as a child how my grandfather’s days would be divided in a very disciplined rhythm. Up from bed by 5:00 a.m. for morning prayers, followed by a routine of breakfast and a brisk walk for an hour (rain or shine), he would then tend to his car— his favorite belonging in equal emotional value to the horses he used to own— before sending us to school at the same precise moment every day. He was a man who meticulously organized time, and he constantly made sure that the hour showing on his mechanical wrist watch, the chiming of the clock on the wall (literally a grandfather’s clock for me), and the Burma Standard Time announced by the local radio station were identical. He constantly called for a horologist to painstakingly adjust and wind his watch and clock.

The gray, classic British car from the Standard Motor Company that took us to school would always reach the yard just before the first morning bell. He was so punctual and precise in his timing that the teachers at my school gave him a bell to ring the time, while he waited for us to finish school. Every day before taking his shower, he would do some kind of physical exercise for about 15 minutes. His well-seasoned habit of keeping up his health and fitness as a sportsman and a jockey never withered.

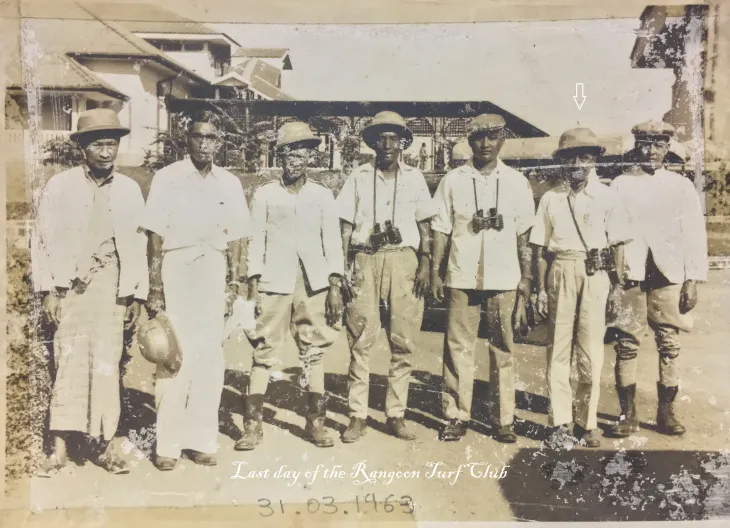

My grandfather’s family came back to Rangoon after the war but the Turf Club activities remained quiet. Only a few years after Burma gained independence, some old jockeys and socialites of Rangoon revived the Turf Club grounds for horse-racing and Thein Pe was appointed as one of the jury members. General Ne Win, a well- known gambler, apart from his other attributes as a dictator and a womanizer, used to regularly spend his weekends at the Turf Club. Rumors had it that Ne Win’s second-wife Khin May Than (Kitty Ba Than), a socialite and already married to a doctor, met him at the race-course and instantly clung onto his car. On March 2nd 1962, Ne Win staged a coup d’état and in the following years privately-owned enterprises were shut down or dissolved under the ownership of the state as part of the “The Burmese Way to Socialism”. The turf club, which entertained the elites and the bourgeois of Rangoon, was closed down, but ironically people saw the tyrant ruler Ne Win travelling every year to Britain at the expense of the State, only to gamble at the British horse races.

Though Thein Pe’s lifetime passion in the world of Burmese equestrian sports was brought to an end, he found more time to devote to his family, especially us grandchildren, and to his religious practices. He would teach me how to read Pali words at home, or take walks with my grandmother to a monastery every evening for a one-hour meditation session. He observed Sabbath days with only the privilege of having his favorite Chinese fried-rice for lunch at his favorite restaurant.

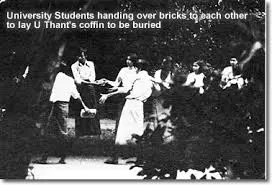

The turf club grounds were used by Ne Win’s government for some events, such as to commemorate Union Day or Peasants Day, until a historical event took place in December 1974 when U Thant, the former Secretary General of the United Nations passed away the month before in New York. According to the last wish of the deceased, the family brought the body back to Burma for burial. U Thant had been a close friend of U Nu, the Prime Minister of the democratic Burma from whom Ne Win took power. When U Thant’s body was laid out for public viewing over several days in the Turf Club-turned-Kyaikkasan grounds, people from all walks of life came to pay their last respects.

In an attempt to undermine U Thant’s legacy, Ne Win’s orders were to dictate the body’s final resting place be in a public cemetery in the West of Rangoon, just like a commoner. The Burmese people, who had endured under the military dictator’s oppressive iron grip for more than a decade, felt insulted for this intentional dishonor toward an internationally known and well-respected figure. Pent-up feelings boiled over, and on the day of the burial, on 5th December, the funeral cortege left the Kyaikkasan grounds according to the dictator’s orders, but upon reaching University Avenue, the many thousands of mourners following the procession and students who were the coffin bearers turned the route into the Rangoon Arts and Science University Campus. They began shouting slogans against the military dictatorship, demanding a fitting and proper final resting place for U Thant. The historic event was known as the “U Thant A-Yay A-Khin” (U Thant Crisis) which ended in a brutal crackdown by the military soldiers, with shoot-outs taking the lives of innocent students. Severe detentions were handed out for the many young students involved, including my future husband and the father of my children.

The vast, walled-off Kyaikkasan grounds have since then been used by the military junta as a temporary detention camp and interrogation center for political suspects, up until the Saffron Revolution in 2007. Some cronies from the military junta era have also tried to use the ample space for their leisurely equestrian training and as a riding club, not to promote proper horse riding skills but rather to purely provide capable horse riders for their junta propaganda and ostentatious military parades. Had he still lived, my grandfather, who adored the equine sports, would be heartbroken to see how the once glorious place of his past has become tarnished with painful memories of the country.

Htay Htay Win is a native of Rangoon and granddaughter to Thein Pe. She enjoyed a long career as liaison and protocol officer at the French Embassy to Burma in Rangoon, before her retirement in 2012. As a 3 year-old girl, she thus grew up very closely under the care of her grandparents, for her mother, the second-daughter of Thein Pe, and her father were both detained as political prisoners without any charges for four years by the Ne Win government.

Like This Article

September 16, 2024

March 06, 2024

December 27, 2023

September 05, 2022

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023