A new special issue in Geopolitics (edited by Jasnea Sarma, Hilary Faxon and K.B. Roberts) highlights pre- and post-coup extractive economies and political geographies in Myanmar and beyond.

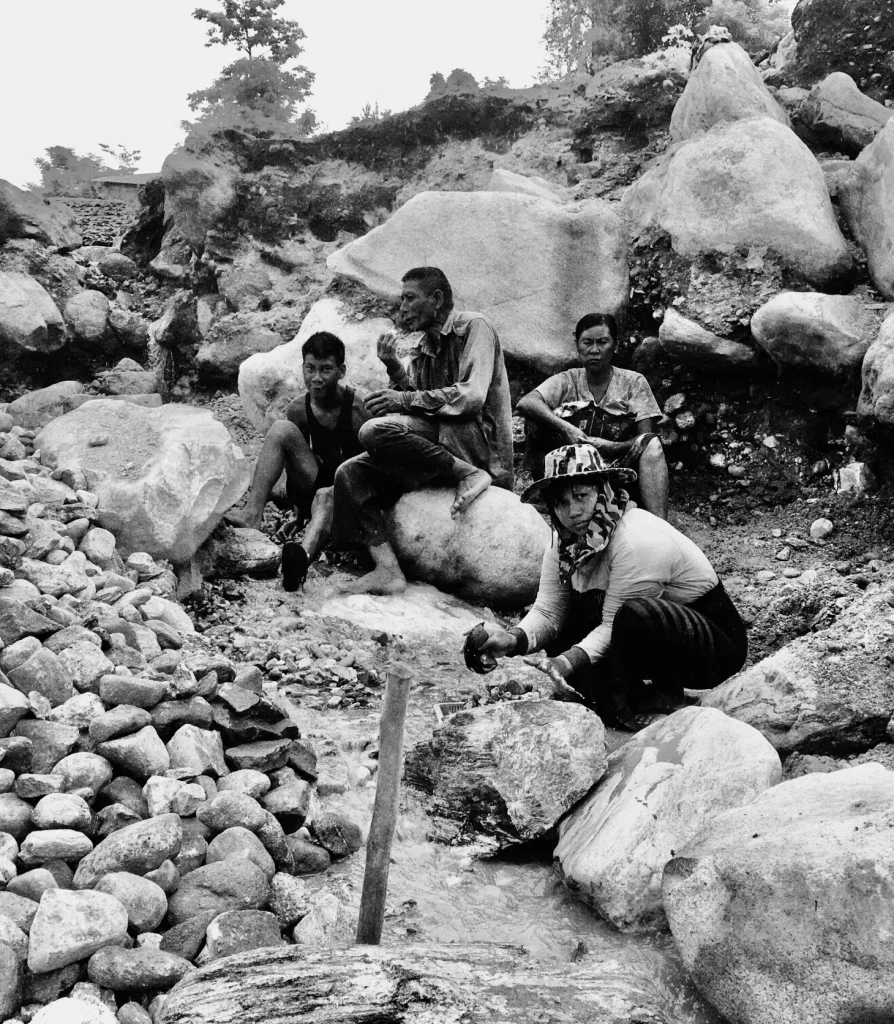

Natural resources have long been central to both the military’s power and everyday livelihoods in Myanmar. A year after the coup, as international oil companies prepare to leave the southwest coast and gold mining spikes in Kachin state, the extraction of environmental commodities remains a key source of military funding, an essential pathway for making a living, and a lever for international pressure. Questions of how resources will be extracted and who will benefit have never been more urgent.

Critical scholars use the concept of “resource frontiers” to highlight the ways in which the commodification of nature produces new socio-spatial patterns, often characterized by opportunity and violence. When lucrative resources are identified for extraction, the resulting rush ignites imaginations and provides new livelihood opportunities while setting off broader processes of accumulation, conflict, and landscape transformation. We find the concept particularly useful in Myanmar, where interlinked processes of extraction and accumulation have long shored up the power of imperial and authoritarian actors while intimately reshaping living landscapes, whether in the oil palm plantations of Tanintharyi, the ruby mines of Mogok, the hydropower projects and jade mines in Kachin state, or new cross-borders projects on the borders of India, China and Thailand.

Our introduction to a new special section provides a historical and ethnographic account of how resource frontiers in Myanmar are remade and lived with, both spatially and in everyday life. As a historical formation, resource frontiers are intertwined with ethnicised/racialized state violence, capitalist extraction and territorialisation. As an unfolding phenomenon, it deeply affects everyday lives, leaving common people displaced, dispossessed and precarious. For critical and interdisciplinary scholars studying Myanmar and its neighbouring environs, these analytics demand careful attention to the long roots and everyday practices that shape extraction, dispossession, enrichment, and violence in the particular places where resources and territory are (re)made and lived with.

In the wake of the coup, as workers strike, People’s Defence Forces (PDFs) seek weapons, and foreign countries impose sanctions, the material basis of military domination has come to the fore. Democracy is not a disembodied idea, but rather a goal that is fought for and carved out on living, inhabited landscapes. In Myanmar, democracy has only so far proved to be an experiment, not a fully functioning polity. Centering the politics of resources is critical not only to understanding levers of change in the Myanmar Spring Revolution, but also for envisioning a functional future federal democracy.

We are proud of the contributions to this collection, which represent a small part of the growing original research on this topic by a new generation of Burma Studies scholars. Our introduction highlights the articles in this collection, which include Elizabeth Rhoads on ethnic and religious minorities and urban dispossession in Yangon, Laur Kiik on nationalist conspiracies surrounding the Myitsone Dam, Frances O’Morchoe on teak and lead among the Lahu and the Wa, Hilary Faxon on agrarian frontier histories and contemporary ethno-territorial projects in Northwest Myanmar and Jelle Wouters on differently articulated projects of ethnic ‘closure’ across the border in Northeast India. From colonial timber extraction to socialist rice production and from borderland territories to urban properties, these papers provide a sense of long and variegated trajectories of resource frontiers and the creative ways that people inhabit and negotiate them.

In celebrating the publication of this collection during these very difficult times, we honour the Myanmar activists, researchers, development workers, farmers, and democracy supporters who have taught us so much. We write today from privileged places, while many of our colleagues and friends remain on the ground. We call for foreign scholars to leverage their positions to continue to support the work and well-being of Myanmar scholars and activists. We also call for researchers to communicate their findings broadly to maintain international pressure on Myanmar’s military, the primary beneficiary of the country’s immense environmental wealth. This short reflection and the collection itself provide a partial, academic perspective on resource frontiers, one aligned with collective action toward more equitable forms of resource distribution and territorial governance in Myanmar. Lastly, we are aware of the deeply problematic political economy of academic articles put behind payrolls and made inaccessibly by powerful publishing houses. We, therefore, ask anyone seeking to read this collection to get in touch with us for full access.

Hilary Faxon is writing a book on land politics and agrarian change in Myanmar. She is currently a Ciriacy-Wantrup Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley.

K.B. Roberts is a political ecologist working on rural livelihood change, deforestation and forest degradation, and feminist research methods. She is currently a PhD Candidate at York University.

Jasnea Sarma is a political geographer studying resources in the India-Myanmar-China borderlands. She is currently a Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Zurich. She can be reached at jasnea.sarma@geo.uzh.ch

Like This Article

March 06, 2024

February 23, 2024

February 22, 2024

November 27, 2023

A new special issue in Geopolitics (edited by Jasnea Sarma, Hilary Faxon and K.B. Roberts) highlights pre- and post-coup extractive economies and political geographies in Myanmar and beyond.

Natural resources have long been central to both the military’s power and everyday livelihoods in Myanmar. A year after the coup, as international oil companies prepare to leave the southwest coast and gold mining spikes in Kachin state, the extraction of environmental commodities remains a key source of military funding, an essential pathway for making a living, and a lever for international pressure. Questions of how resources will be extracted and who will benefit have never been more urgent.

Critical scholars use the concept of “resource frontiers” to highlight the ways in which the commodification of nature produces new socio-spatial patterns, often characterized by opportunity and violence. When lucrative resources are identified for extraction, the resulting rush ignites imaginations and provides new livelihood opportunities while setting off broader processes of accumulation, conflict, and landscape transformation. We find the concept particularly useful in Myanmar, where interlinked processes of extraction and accumulation have long shored up the power of imperial and authoritarian actors while intimately reshaping living landscapes, whether in the oil palm plantations of Tanintharyi, the ruby mines of Mogok, the hydropower projects and jade mines in Kachin state, or new cross-borders projects on the borders of India, China and Thailand.

Our introduction to a new special section provides a historical and ethnographic account of how resource frontiers in Myanmar are remade and lived with, both spatially and in everyday life. As a historical formation, resource frontiers are intertwined with ethnicised/racialized state violence, capitalist extraction and territorialisation. As an unfolding phenomenon, it deeply affects everyday lives, leaving common people displaced, dispossessed and precarious. For critical and interdisciplinary scholars studying Myanmar and its neighbouring environs, these analytics demand careful attention to the long roots and everyday practices that shape extraction, dispossession, enrichment, and violence in the particular places where resources and territory are (re)made and lived with.

In the wake of the coup, as workers strike, People’s Defence Forces (PDFs) seek weapons, and foreign countries impose sanctions, the material basis of military domination has come to the fore. Democracy is not a disembodied idea, but rather a goal that is fought for and carved out on living, inhabited landscapes. In Myanmar, democracy has only so far proved to be an experiment, not a fully functioning polity. Centering the politics of resources is critical not only to understanding levers of change in the Myanmar Spring Revolution, but also for envisioning a functional future federal democracy.

We are proud of the contributions to this collection, which represent a small part of the growing original research on this topic by a new generation of Burma Studies scholars. Our introduction highlights the articles in this collection, which include Elizabeth Rhoads on ethnic and religious minorities and urban dispossession in Yangon, Laur Kiik on nationalist conspiracies surrounding the Myitsone Dam, Frances O’Morchoe on teak and lead among the Lahu and the Wa, Hilary Faxon on agrarian frontier histories and contemporary ethno-territorial projects in Northwest Myanmar and Jelle Wouters on differently articulated projects of ethnic ‘closure’ across the border in Northeast India. From colonial timber extraction to socialist rice production and from borderland territories to urban properties, these papers provide a sense of long and variegated trajectories of resource frontiers and the creative ways that people inhabit and negotiate them.

In celebrating the publication of this collection during these very difficult times, we honour the Myanmar activists, researchers, development workers, farmers, and democracy supporters who have taught us so much. We write today from privileged places, while many of our colleagues and friends remain on the ground. We call for foreign scholars to leverage their positions to continue to support the work and well-being of Myanmar scholars and activists. We also call for researchers to communicate their findings broadly to maintain international pressure on Myanmar’s military, the primary beneficiary of the country’s immense environmental wealth. This short reflection and the collection itself provide a partial, academic perspective on resource frontiers, one aligned with collective action toward more equitable forms of resource distribution and territorial governance in Myanmar. Lastly, we are aware of the deeply problematic political economy of academic articles put behind payrolls and made inaccessibly by powerful publishing houses. We, therefore, ask anyone seeking to read this collection to get in touch with us for full access.

Hilary Faxon is writing a book on land politics and agrarian change in Myanmar. She is currently a Ciriacy-Wantrup Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley.

K.B. Roberts is a political ecologist working on rural livelihood change, deforestation and forest degradation, and feminist research methods. She is currently a PhD Candidate at York University.

Jasnea Sarma is a political geographer studying resources in the India-Myanmar-China borderlands. She is currently a Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Zurich. She can be reached at jasnea.sarma@geo.uzh.ch

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023