Kikuchi Taihei argues that Myanmar’s federalism and national identity roots trace back to Hkun Kyi’s advocacy.

Myanmar chose a unitary state as its governing ideal when it gained independence in 1948. This is significant not only for today’s politics but for national identity. In this context, the Panglong Conference is repeatedly recalled as the place where representatives of lowland Burma[1] and ethnic minorities promised to establish a federal state. Among ethnic minorities, the Panglong Conference in 1947 is remembered as the event where Aung San, the hero of Burma’s independence, promised to build a nation based on a federal system. Yet, the junta and the government have legitimized their own rule by extolling the Panglong Conference as source of national unity while positioning the military, created by Aung San, as the guardian of the nation (Walton 2008).

Despite the Panglong Conference’s contemporary relevance, historical investigations into this pivotal event, particularly regarding the Chiefs of the Federated Shan States who hosted the conference, have been notably scarce. The conference, held in March 1946 and February of the following year, was orchestrated by the Chiefs who governed Shan States. Their original intent was to deliberate on the future of their war-torn states and their relations with lowland Burma. The two conferences saw the participation of representatives from the Kachin, Chin, and Burmese groups, as well as the commoners whose political agitation against feudalism had been growing in the Shan region since the late 1930s. Despite the Chiefs’ efforts, their role in the historic Panglong Agreement, which was reached on February 12th, 1947, remains underestimated.

One idea of federation provided the foundation for the Chiefs’ attitudes at the Panglong Conference. It was Sao Hkun Kyi (1901-1947) who advocated for the construction of a “United States of Burma” in the 1930s. His idea stimulated not only other Chiefs but also young activists in the Shan area. What were the conditions of federalism for Hkun Kyi, who was the first to advocate for it in Myanmar?

Several states existed in the Shan region since pre-modern times and were ruled by Chiefs of varying levels. At the top, the Saophas had the most authority. Next in line were Myosas and Gwegunhmus, who ruled over towns and villages (Sanda Simms 2017, p. 27). After the Anglo-Burmese wars, the colonial administration directly governed the lowlands where the Burmese were the majority, and indirectly controlled the outlying areas where ethnic minorities lived, including the Shan States. After the annexation of Burma and the Shan States into the colonial administration, the British gave the Chiefs deeds called Sanad between 1886 and 1897, which provided a legal basis for their limited sovereignty (Great Britain 1947, pp. 12-13).

Sao Hkun Kyi was one of the Chiefs in the Shan States. He was born to Sao Hkun Hseng (1879-1901) of the Hsahtung Myosa, and his mother, Daw Ma Ma Gyi in 1901. He was a man of both Shan and Pa’O lineages. Hsahtung State was a small town of about 500 square miles populated with about 15,000 (Tun Myint 2016, pp. 219-220). Hkun Kyi was educated at the Shan Chiefs’ School in Taunggyi and St. Paul’s Christian School in Rangoon and then studied at the Insein School of Industrial Sciences (Sanda Simms 2017, p. 326).

During his adolescence, the outbreak of World War I in 1914 had a significant impact on British India. The diarchal form of the Government of Burma was introduced because the anti-colonial nationalist struggle was gaining momentum in both India and Burma. Before this administrative reform, Shan States were integrated as the Federated Shan States in 1922. At the same time, the Federal Council of Shan Chiefs was established as an advisory body, and Saophas and colleagues were appointed members (Great Britain 1947, pp. 13-14).

In 1930, Hkun Kyi inherited the Myosa of the Hsahtung State, marrying Daw Aye Thant, the daughter of an Inle trader, and making a living in business (Sanda Simms 2017, p. 326). At the time, the British were about to extend autonomy to the lowlands of Burma. As the struggle against colonialism in British India escalated, the colonial government had to adjust the autonomy of the locals. This was not only for India but for Burma. In Burmese politics, the processes had significant meaning: the separation from British India and the improvement of its status in the colonies. After the India Round Table of 1930-31 and the Burma Round Table of 1931-32, the British established the Government of Burma Act in 1935 and granted it separation from British India in 1937, making Burma a direct colony.

Upon the separation, the Federated Shan States confronted a fundamental question: whether they would remain a part of British India or become a part of Burma. Chiefs represented the Federated Shan States at the India Round Table of 1930-31 and the Burma Round Table of 1931-32. There, the representatives explained that if the Federated Shan States needed to be linked to Burma, the Federated Shan States should not be annexed as a unitary state but organized as a federation (Shwe Ohn 2014, pp. 103-108).

But the decision as to whether the Federated Shan States would be united with Burma or not, was deferred because of the Government of Burma Act. The Act separated Burma from India while excluding the outlying areas from the lowland polity. The lowland, known as “Ministerial Burma” was placed under a different government system as Scheduled Areas. This is the so-called divide and rule policy.

The next opportunity to consider the relationship between the Shans and Burma came after World War II. Sao Hkun Pan Sin (1894-1975, The Saopha of Tawngpeng State), Sao Sam Htun (1907-1947, The Saopha of Mong Pawn State), and Hkun Kyi called for a meeting to discuss the annexation of minor states within the Federated Shan States (the Mong Kung Discussion). In March 1946, the Chiefs of Laikha, Mong Kung, and Mong Naung called for another conference to discuss issues in the Federated Shan States, which is now called the first Panglong Conference (UHRC 1999, vol. 1, pp. 107-213). Hkun Kyi unfortunately could not participate in the second Panglong Conference held in February 1947 himself due to deteriorating health, yet his significance was undeniable, as we can see U Pyu’s signature on behalf of Hkun Kyi in the Panglong Agreement.[2] It can be said that Hkun Kyi contributed significantly to convening the Panglong Conference.

Shan activists[3] tended to regard Hkun Kyi as the first person who awakened the Shan ruling class and engaged in political activities. Even though he is still not well known in modern Myanmar history, he has been highly praised by the Shan activists who supported amalgamation with lowland Burma at independence. Tun Myint (Taunggyi), for example, recounted in his memoirs that the support of Hkun Kyi led him to become involved in political campaigns. Hkun Kyi was regarded as a man who fought for the Federated Shan States to become democratic and make a federal country with Ministerial Burma (Tun Myint 2016, pp. 219-220). Shwe Ohn also stated, “Among the ruling class of Shan States, the first to awaken and become active in politics was Hkun Kyi.” He listened well to the commoners of the Federated Shan States and demanded the federal system between Shan and Burma (Shwe Ohn 2014, pp. 103-108).

When the Federated Shan States confronted the problem of the relationship with the lowland Burma, Hkun Kyi wrote the pamphlet, “The Errors of the Shan States.” This was published in 1940. It consists of a cover, introduction (1p.), main part (17 p. / written in 1935), commentary (4p. / no date), and appendix (7p. / written in 1940 / correspondence with Sam Htun, the Saopha of the Mong Pawn State).

Hkun Kyi demanded that the Federated Shan States be incorporated into Burma. In the pamphlet, he discussed the historical and political relationship between the Shan and Burmese ethnic groups. In criticizing the report of the Simon Commission, which was organized in 1928 and aimed at reforms in the constitutional structure of British India, he highlighted the intertwined history of the two groups, including periods of struggle for supremacy and the impact of various ruling dynasties. He argued that despite occasional conflicts, there had been close cultural, economic, and intellectual exchanges between the Shan and Burmese communities.

The Federated Shan States covered an area of 56,000 square miles with a population of 1.5 million. Revenues totaled approximately Rs. 8,500,000, of which Rs. 5,800,000 went to the Federal Budget, and the rest was spent within each state. The Federal Budget included revenue from the Government of Burma’s control of forests and minerals in the Federated Shan States. Still, it faced financial challenges, especially after the expected cessation of Burma’s subsidy in 1932. This would lead to a minimum yearly deficit. The individual states suffered under a system in which Chiefs’ allowances were based on a percentage of state receipts, driving them to increase revenues.

Therefore, complete separation from Burma and the status of an autonomous section of the British Empire is a utopian conception, pleasing to toy with, but impossible of realisation as a matter of practical politics. No country situated as ours is in the midst of a group of states could possibly survive an isolated existence. We are a small sparsely populated country wedged in-between Burma, Siam, China and French Indo-China, and if the ideal of isolated self-government raises our enthusiasm, we must first consider of stern military necessity. Independence connotes more than anything the ability to stand on our own feet not only from the point of view of numbers but more so from an economic point of view (Hkun Kyi 1940, p. 10).

The idea of complete separation from the Ministerial Burma and autonomy of the Federated Shan States within the British Empire was deemed impractical.

As shown above, Hkun Kyi pointed out that the Federated Shan States rely on Burma for resources and capital. They could not expect to borrow from elsewhere. If they remained politically isolated from Burma, they risked facing a future tariff war with the self-governing Burma. Since the Federated Shan States depend on Burma for both exporting their products and importing goods, any imposition of tariffs by Burma on goods from the Federated Shan States would severely impact their existence. Hkun Kyi even stressed the heavy dependency with statistics: with exports to Burma totaling 80,000 tons and imports from Burma only 25,000 tons (Hkun Kyi 1940, p. 11). This is how Hkun Kyi stated that the relationship between Shan and Burma is inseparable and necessary.

In addition, Hkun Kyi noted that the new Government of India Act would allow for the participation of Indian Rulers and Chiefs in the future government as a dominion of the British Empire. Burma would also become such a dominion. If the great rulers of India were willing to cooperate for the advancement of freedom, Hkun Kyi noted, the Shan Chiefs also had to do that. Efforts should be made to strengthen the link between Burma and the Federated Shan States. Given this understanding, representing the Federated Shan States as a geographical subdivision of Burma at the Round Table Conferences was crucial. Through the cooperation with Burma, the demands and aspirations of the Federated Shan States could be voiced effectively (Hkun Kyi 1940, p. 11).

Despite the necessities of the cooperation between Shan and Burma, he criticized, Saophas who had the responsibilities for governing were never united. He wrote,

This is the point where Hkun Kyi’s argument for the “a Shan Commoners’ Council” came in. He urged for the nation to unite, stating that the commoners should first unite and set an example for the Chiefs who lacked union for the Federated Shan States.

For the state to come together, the commoners must first be united, and the “Shan Commoners’ Council” was set forth as a means of achieving this.

In this situation, Hkun Kyi concluded that Ministerial Burma and the Federated Shan States should be on equal footing and create the “United States of Burma.” In this “United States of Burma,” he envisioned the addition of a Shan representative to the Union Council on the Ministerial Burma and the organization of a bicameral Council on the Federated Shan States side, at least 90% of whose representatives would be from the Federated Shan States, and no more than 10% of whose representatives would be from Ministerial Burma. Besides, the department staff of forestry, mineral, economy, industry, agriculture, finance, education, and transportation in the Federated Shan States would be Chiefs or natives elected by the state (Hkun Kyi 1940, pp. 13-15).

Hkun Kyi did not deny the possibility of separation of the Federated Shan States from Burma. He noted that Shan was located in central Burma and enjoyed independent status until the early modern period, even though the natural resources were underdeveloped. So complete independence could continue if the people wished to. However, he added that becoming independent and separate from Burma would not be easy and that it was essential for everyone to be united, whichever of the above two would be chosen (Hkun Kyi 1940, pp. 14-16). It was stressed that a nation could be created only when all the country’s compatriots are united.

To summarize, Hkun Kyi emphasized the unity of the Federated Shan States. It was urged that the governance of the Federated Shan States should be carried out by the respective Chiefs and the commoners who lived there. At the same time, he believed it would be impractical to do so apart from lowland Burma. This is because he concluded that the Federated Shan States must work with the government of Burma if it were to form an autonomous government independent of British India.

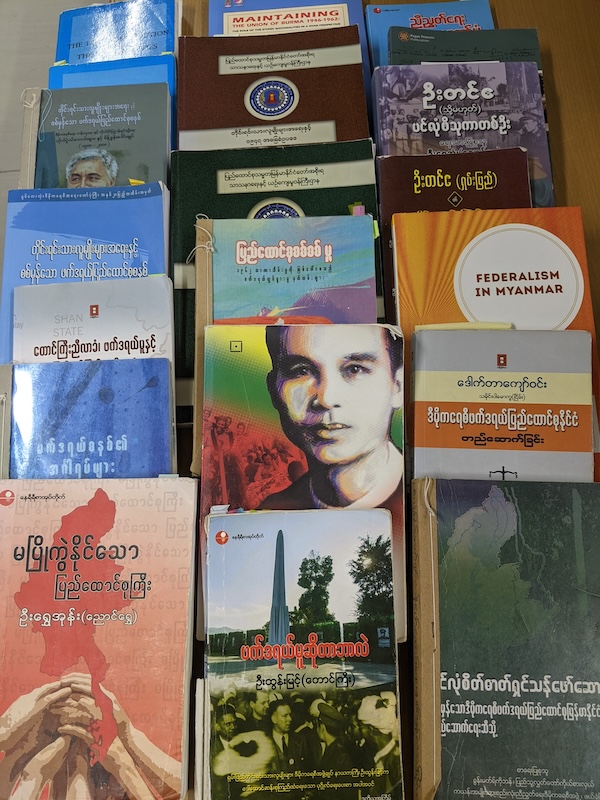

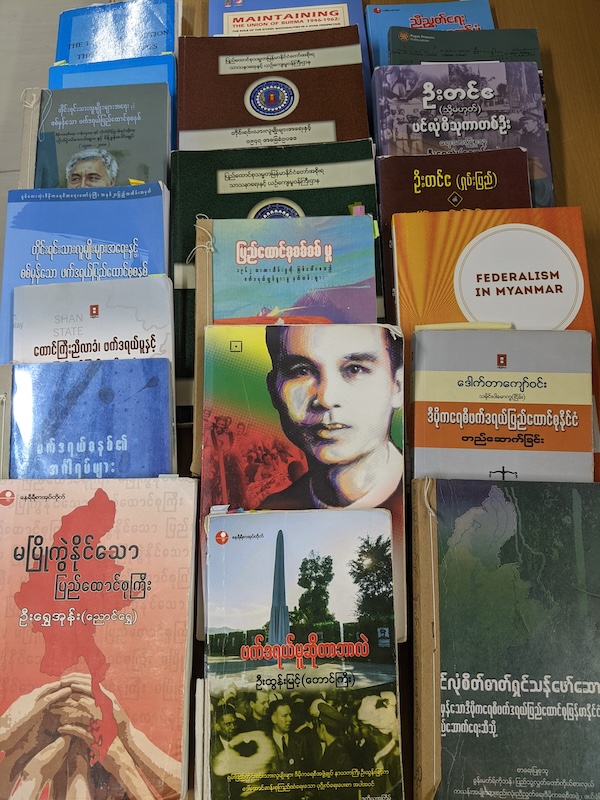

Those claims preceded all other conceptions of federalism in Myanmar. After a decade of independence, ethnic minorities including Shan activists started to demand the amendment of the 1947 Constitution. Requirements for “true” federalism led by Tun Myint (Taunggyi) resulted in calls for the Taunggyi Conference in 1961 and the Federal Seminar in the following year. A series of political activities are now known as the Federal Movement. Even though it failed because of the Coup d’état of 1962, the demands reappeared in the 1988 uprising. Moreover, contemporary ethnic minority parties are calling for the introduction of federalism regarding the Panglong as the dawn of federalism (cf. SNLD 2020). It can be said that Hkun Kyi’s federalism continues to live on, changing across historical contexts.

Project description: This piece is an outcome of the workshop, “Plural Pasts for Collective Futures in Burma/Myanmar: Histories of Belonging and Identities (Re)Imagined,” hosted by York University in 2023. Funded by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Connection grant, the 2-day workshop invited 12 Burma Studies scholars who are based in Japan or Canada to engage in fruitful, interactive discussions and strengthen the scholarly network more internationally to think about Myanmar’s future.

Taihei Kikuchi is a research fellow at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University. He is interested in the process of nation-state formation in Myanmar and the narratives of national unity.

Notes

Like This Article

June 18, 2024

March 06, 2024

February 23, 2024

February 22, 2024

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023