Xu Peng analyses Kokang’s tumultuous past and its ongoing impact on Myanmar’s politics.

The ‘Operation 1027′ offensive in Northern Shan State, Myanmar, stands as a crucial juncture in the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army’s (MNDAA) enduring quest for autonomy in the Kokang region. This coordinated offensive against the Myanmar military by the brotherhood alliance, comprised of three insurgent groups – the MNDAA, the Ta’ang National Liberation Organization, and the Arakan Army – has catapulted Kokang back into the center of Myanmar’s multifaceted conflicts, and resonates with the 2009 Kokang incident. In that year, the Myanmar Military’s raid on a factory in Kokang triggered hostilities with the MNDAA, epitomising the tenuous nature of the ceasefire with the state. This resulted in the MNDAA’s defeat after which Kokang predominantly fell under the aegis elements of the MNDAA which had ‘gone over’ to the Union, and which were reconstituted as the Kokang Border Guard Force (BGF). Subsequent years saw recurrent skirmishes, with a 2015 clash being notably significant, resulting in an exodus of 100,000 refugees to China.

This commentary delves into the historical continuity of the Kokang mutiny, tracing its roots and impact through time. It aims to unravel the persistent nature of conflict in Kokang, highlighting how the region’s history, from its earliest rebellions, has been inexorably shaped by global geopolitical dynamics. This exploration seeks to offer a comprehensive understanding of Kokang’s tumultuous past, contextualising its current situation within a broader historical framework based on multiple archival resources.

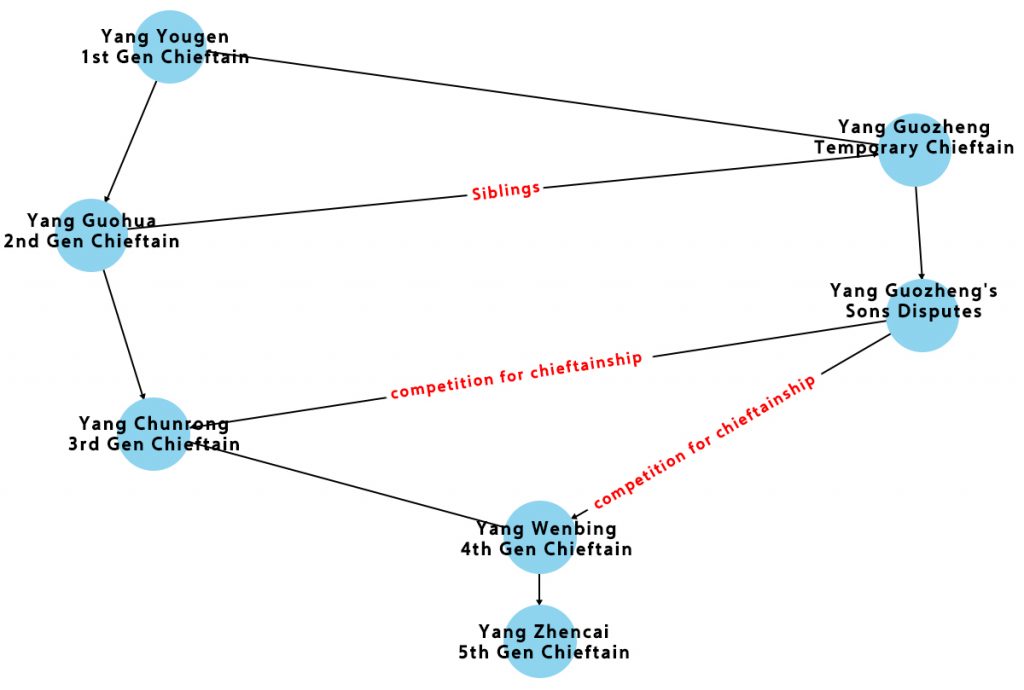

Formerly under Imperial China, Kokang was ceded to British India, of which Burma was a part, in 1897. Despite this, the Yang family, local chieftains known as Myosa to the British, maintained substantive control. The relationship between the Yangs and the British was largely harmonious. However, the succession of chieftains within the Yang family was marked by disputes. The first-generation chieftain, Yang Yougen, had two sons: the elder, Yang Guohua, and the younger, Yang Guozheng. Upon Yougen’s death, Guohua became chieftain. However, Guohua’s son, Yang Chunrong, was too young to assume the role of chieftain when Guohua passed away. Consequently, Guozheng temporarily took over as chieftain.

When Chunrong matured, Guozheng handed over the leadership to him, sparking the first major dispute. Guozheng’s sons also claimed rights to the chieftainship, leading to divisions within Kokang. This conflict escalated and, in 1929, necessitated British colonial intervention. Yang Wenbing, Chunrong’s son, was ultimately recognised as the fourth chieftain. In 1941, his son, Yang Zhencai (Sao Edward Yang Kyein Tsai), became the fifth chieftain. The succession disputes within the Yang family, while complex, resulted in only limited British involvement. It was the Yangs who sought British arbitration, highlighting the strategic interaction between local dynamics and colonial influence during this period.

Japan invaded Burma in the spring of 1942; after they occupied southern Burma, they moved north, aiming to destroy the Burma Road, which linked Southwest China and Northern Burma. Kokang, situated north of the confluence of the Namting and Salween rivers, lay between the British and the Japanese front lines. Since the loss of Burma in April 1942, no British troops had been stationed in Kokang, which found itself in an increasingly precarious situation; thus, Kokang chieftains sought help from then – Kuomintang (KMT) – controlled China, and showed their willingness to be territorially restored to China in exchange for military help from the Chinese Expeditionary Army (CEA)[1]. The KMT not only agreed to help Kokang establish the Kokang (Anti-Japanese) Defence Force (KDF) in collaboration with the CEA in 1942, but they also admitted Yang Wenbing’s nephew to the KMT military academy in Chengdu, China, for military training.[2]

However, in September 1943, a mutiny within the KDF occurred. Yang Wenbing, under attack by a KDF faction led by his own cousin Yang Wentai[3]; managed to escape with a fractured leg[4], but his son was killed. While appearing as an internal family strife, this mutiny also involved the CEA, which suspected Yang Wenbing of collaborating with the Japanese, in part because of his coerced attendance at a Japanese-held conference in Kunglong in 1942. After fleeing to China, the chieftain was detained on charges of ‘cooperating’ with the Japanese. Following months of investigation, he was released without charge. The mutiny was an attempt by Yang Wentai to replace the chieftain by falsely accusing him of complicity with the enemy.

This internal mutiny drew the attention of both the British and Chinese authorities, and served to raise two critical issues. Firstly, it caused distrust between Kokang, China, and the British, with investigations scrutinising the chieftain’s alleged complicity with the enemy. Secondly, China’s involvement in Kokang was multi-dimensional: it was both a response to the Kokang chieftain’s appeal for assistance and a strategic move to prevent any potential collaboration between Kokang and Japan, given the region’s significance in the broader warzone. However, this proactive stance by China raised concerns for the British. The crux of these concerns centred on the extent of China’s jurisdictional rights, particularly in detaining and potentially prosecuting the Kokang chieftain. The British apprehension was not only about international legal boundaries but also about the implications such actions might have on regional stability and their own strategic interests[5]

Between 1947 and 1989, Kokang experienced profound shifts in leadership dynamics, paralleling significant political transformations in Burma. After gaining independence in 1947, Kokang witnessed the abolition of its hereditary chieftain system by 1959 under Ne Win’s caretaker government. This change paved the way for regional ethnic autonomy, with a local council led by the Yang family assuming administrative and judicial control. This scenario altered drastically post-1962 following Ne Win’s coup[6], which resulted in the dissolution of parliament and the loss of Kokang’s parliamentary representation. This event signalled the end of the earlier ‘deal’ that had allowed Kokang to merge into the federal structure while retaining a degree of autonomy. Consequently, Kokang’s focus shifted towards defence against the Myanmar government, necessitating a move from hereditary leadership – Yang Wenbing was ultimately the last chieftain – to a model prioritising capability and effectiveness in governance.

During the Cold War, Kokang emerged as a significant conflict zone, strategically positioned between the retreating KMT forces of the Republic of China in the 1950s and 1960s and the rising Communist Party of Burma (CPB) from the 1960s onwards in the China-Myanmar borderlands. The retreat of the KMT to the border facilitated a co-option with Yang Jinxiu, also known as Yang Kyin Hsui or Olive Yang, the daughter of Yang Wenbing. This collaboration led to the establishment of the Xincheng Refresher military training school in Kokang[7], which shaped future Kokang leaders like Peng Jiasheng (Pheung Kya-shin) and Luo Xinghan (Lo Hsing Han), who would later command their own armed factions.[8]

By the mid-1960s, the formation of a defence force in Kokang aimed at opposing the Myanmar government became evident. Some members of the Yang family and Lo opted to align with the Myanmar government. In contrast, Peng led a guerrilla movement and, by the late 1960s, decided to join forces with the CPB to bolster Kokang’s military capabilities. This period widely illustrated Peng’s close ties with China, as he leveraged the CPB’s support in his struggle against the Myanmar government.

The abolition of Kokang’s chiefdom system marked a shift in leadership criteria, moving from hereditary rights to the aforementioned focus on leadership capacity. This transition led to continuous internal mutinies, underlining the tension between claims of legitimate rule and actual governance ability. Historically operating under an ‘Imperial shadow’, Kokang leaders strategically shifted allegiances, often aligning with more dominant powers. This resulted in numerous domestic factions in the mid-1960s, personified in the Yangs and Lo on one side and Peng on the other. These Kokang struggles thus transcended local concerns and played out in line with external ideological and political alliances, as observed by Cai Shan (author of Kokang).[9]

In the 1990s, Kokang experienced what appeared to be a continuing historical cycle of mutinies and shifts in power. In March 1989, Peng led the first mutiny within the CPB, forming the MNDAA. This move prompted Wa and other factions within the CPB to break away, a step understood as part of a deal with the then- Myanmar government which allowed a degree of autonomy for these ethnic groups in exchange for them not supporting the nascent democratic movements in Bamar-majority areas. However, Kokang’s period of relative peace was short-lived. Further mutinies followed which received scant media attention. A significant conflict arose between Peng Jiasheng and his vice-deputy, Yang Maoliang, with Yang harbouring longstanding grievances against Peng which pre-dated the CPB mutiny. In November 1992, Yang, with 2,000 of his own soldiers and the additional support of over 1,000 soldiers provided by the United Wa State Army (UWSA), launched an attack on Peng; despite the latter’s numerical superiority (Peng had 4,000 soldiers)[10], he lost, and went into exile in early 1993. This event preceded Peng’s more widely witnessed exile following the 2009 Kokang incident. After Peng’s 1993 departure, Yang assumed the chairmanship, appointing Bai Suocheng (Bai Xuoqian) and Wei Chaoren to key military positions, thus laying the groundwork for future factional divisions in 2009.[11]

Yang’s consolidation of power was short-lived. By the autumn of 1995, Kokang faced renewed internal conflicts. With UWSA assistance, Peng regained control of Kokang in November 1995, marking the region’s second major mutiny since it gained autonomy in 1989. These conflicts in the 1990s, distinct from the Cold War-era mutinies, more closely mirrored disputes from the chieftain period, characterised mainly by internal strife and limited external intervention. Unlike previous eras, the involvement of the incumbent Myanmar state was not a major factor in the factional divisions within Kokang; neither faction sought to leverage government support against the other. Instead, the significant role of other Ethnic Armed Organizations or EAOs, particularly the UWSA, marked this period. Wa involvement on both sides of the mutinies stemmed from their strategic ambitions. They aimed to support Yang in 1993 to counterbalance the rise of Khun Sa, a prominent figure in regional power dynamics; they supported Peng in 1995 to restrict the expansion of Yang’s drug trade.

In the 21st century, Kokang’s narrative took a global turn. After Peng and the MNDAA returned to Kokang in the winter of 1995, they shifted focus towards economic development, notably the gambling industry. Kokang’s economy, thriving largely due to its casinos (see Figure 2), was even likened to ‘the next Macau’. However, in August 2009, Kokang witnessed renewed clashes, this time involving the MNDAA and the Myanmar government, triggered by an incident where Burmese policemen died during a factory inspection. Although it appeared to be a conflict between the MNDAA and the state, it was, in essence, a mutiny against Peng led by the Bai family with the Myanmar government’s support.[12] Post-coup, Bai assumed the chairman role in Kokang, and transformed his soldiers into a BGF.

This 2009 conflict and Peng’s failed attempt to ‘return home’ in 2015 marked a shift in the nature of Kokang’s mutinies. No longer regarded as local affairs, these clashes rippled through Myanmar’s domestic politics and garnered increasing attention from both China and Western nations. On the one hand, the 2009 clashes signified the Myanmar government’s formal assertion of control in Kokang, with the BGF positioned not just along the China-Myanmar border but also adjacent to other EAOs, serving as a warning to these groups against potential anti-government strategies. On the other hand, with Myanmar’s democratic transition starting in 2010, Kokang’s place in Sino-US relations gained prominence. The manner in which China handles the situation in Kokang, especially concerning border security, places it in a challenging position with respect to its policy of non-intervention.

Examining the history of Kokang’s mutinies from its origins to the present day is instrumental in understanding the transformation of internal clashes into multifaceted factional conflicts influenced increasingly by external political forces. The 1027 operation (see figure 3) in 2023, initially perceived as another attempt by Peng’s MNDAA to ‘return home’, transcends this interpretation. The fight has evolved into a more significant movement, garnering support from various EAOs. The objective has shifted beyond defeating the Kokang BGFs to challenging the State Administration Council (SAC). This development signifies that the Kokang conflicts are no longer confined to regional issues but have become emblematic of a broader resistance against the Myanmar junta, highlighting a rising power dynamic in the region.

Author’s note: This article is an excerpt from a longer article about Kokang’s history (forthcoming)

Xu Peng is a PhD candidate in the Department of Politics and International Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, UK. Her research focuses on the history of ethnic armed groups in the China-Myanmar borderlands. (Follow her on X: @XuPeng72881167)

Notes

Like This Article

September 11, 2024

April 09, 2024

February 23, 2024

February 22, 2024

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023