Pia Joliffe reviews a historical fiction book on early modern Southeast Asia.

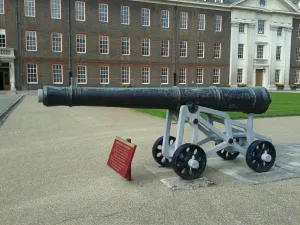

During a walk through the Royal Chelsea Hospital, I recently encountered, in the courtyard next to the flagpole, a display of a cannon made in 1623 in the Sultanate of Singora (today: Songkhla). The cannon bears the seal of Sultan Sulayman Shah. From the plaque attached to the artefact I learned that the cannon was used during the siege of Ayuthia where it was captured by Burmese forces in 1767. During the Third Anglo-Burmese War (1885-1887), the cannon was taken by the British to the United Kingdom.

The history of this artefact in Chelsea, a district of London, epitomizes the interrelatedness between the histories of today´s modern nation-states Thailand, Myanmar, and the United Kingdom.

The historical fiction The Cannon Soldiers of Burma also uses the stories around historical artifacts – cannons- as a starting point to retell the history of early Portuguese settlers in Burma. The book is based on events spanning from the arrival of the first Portuguese ships in 1510 to 1613 when thousands of Portuguese became prisons of war in Ava, and 1630 when the Portuguese prisoners were released and given territory to settle between the valley between the two rivers Chindwin and Mu. The author, James Myint Swe, is a descendant of Portuguese settlers who arrived in 1510 in Pegu (today: Bago). Today he lives and works in Canada. In February 2015 Burma Campaign UK hosted the book launch of The Cannon Soldiers of Burma in London and this is how I met the author and obtained a copy of the book.

The Cannon Soldiers of Burma reconnects the relationship between the different peoples of Burma (Arakan, Mons, and Bama/Burmans) and the Portuguese who arrived as merchants and mercenaries and became at times close friends and allies to territorial lords, and at other times their adversaries. The novel has four interconnected plots. Part one (pp. 3-95) consists of twelve chapters that introduce the history for the Portuguese merchants and mercenaries in Burma. The first chapter is set at the Portuguese naval base in Goa, India, in 1511 and describes the preparations for the Portuguese fleet’s departure towards the East and offers a dense description of the close encounters between the Portuguese mercenaries, the Rahkine people in Arakan and the Mon people in Pegu. In this multilingual and multi-ethnic setting, the role of interpreters was crucial. Part two (pp. 99-175) has nine chapters. The sequence starts out in Pegu in 1540 and then moves on to Martaban and the battles of Arakan and Siam in 1542. At that time, the Burmese army was multi-ethnic and consisted of almost one hundred Shans, Mons, Karens, and more than seven hundred Portuguese cannon soldiers and gunners plus an additional three thousand Japanese, Armenian, Turk, and Javanese foot soldiers. Thousands of elephants and horses were to be transported with the soldiers. Chapter eighteen introduces Felipe de Brito de Nicote and his Goa-born wife Dona Luisa de Saldanha. In 1602 de Brito was appointed the governor of Syriam and involved in the events that led to the Taungoo king Natshinnang´s conversion to Christianity in 1612.

One of the most shocking scenes of the book is the capture of Syriam by the Ava king Anaukpetlun and the execution of both Felipe de Brito and king Nathsinnang. While the latter was dealt with quickly and without public attention, Felipe de Brito was publicly tortured and his body was put on display on a bamboo pole. It was thus that Louisa saw her husband before she was captured and brought together with hundreds of Portuguese prisoners during a seventy-five-day journey from Syriam to Ava. Part three (pp. 179-245) continues from there and describes in seven chapters the seventy-five days’ journey of thousands of Portuguese prisoners to Ava. During these years of humiliations and hardships, physical and spiritual healing was offered by Christian priests and Buddhist monks. The priests were prisoners themselves and thus prayed with the other prisoners, and celebrated mass and funerals. Buddhist monks, in turn, were able to influence Nga Toke, the commander who was put in charge of the Portuguese prisoners to treat the captives kindly. The Portuguese stayed in a prisoner camp in Ava for five-teen years until king Thalun eventually set them free. Once released, the Portuguese established themselves within a few years along the Mu river in the so-called Two Rivers Valley. Part four (pp. 249-270) is the shortest part of the book, consisting of two chapters. It is a sequel to the preceding chapters and describes the lives of the Portuguese in the two river valley. As time passed, the Portuguese learned the local languages and customs and increasingly settled down and married local women.

The author´s approach is a writing style of telling the story as an all-knowing narrator. Nevertheless, the narrative focuses rather on particular incidents without providing more general information about the larger context of the global history of colonialism and Christian missionaries. Thus the author can make moral judgments whilst avoiding political ones. For example, the ethical and political implications related to the deaths of Felipe de Brito (p. 158-159) and his son Simon de Brito (p. 171) remain unexplored: were father and son de Brito martyrs executed for their faith? What were the international reactions to these killings and how did these incidents impact future diplomatic activities between Europe, precolonial, colonial and postcolonial Burma? Whilst these political questions remain unresolved, a moral judgment concerning the cruel treatment of Portuguese prisoners is clearly made through the speech of the chief monk, Sayadawgyi (p. 199-200) who helps the Burmese commander understand that the harsh treatment of the prisoners is against the teachings of the Buddha.

An appendix with a timeline of the major events of the book would have been helpful. Also, a more comprehensive map with all the places mentioned in the novel would have been useful, as well as more detailed information about the artwork which has been chosen as cover and front matter.

Dr Pia Jolliffe is a Research Scholar at the Las Casas Institute, Blackfriars Hall, University of Oxford. She holds a DPhil in International Development (Univ of Oxford) and a MPhil in Japanese Studies (Univ of Vienna) Her book Learning, Migration and Intergenerational Relations. The Karen and the Gift of Education (Palgrave Macmillan) analyses the role of education in the lives of the Karen people in Myanmar, Thailand and the UK.

Like This Article

September 16, 2024

March 06, 2024

December 27, 2023

September 05, 2022

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023