Nicolas Salem-Gervais, on the prospects of teaching ethnic histories when decentralizing education.

This is Part Three of a three-part series – which forms a much shorter and more opinion-based version of an upcoming academic work (Salem-Gervais 2019) – aimed at offering a new perspective, and stimulating constructive debates, on several aspects of the representation of ethnic identities in Myanmar’s national education system, especially questions of languages.

Successive governments in Myanmar, like in many countries around the world, have used schooling, textbooks and history curricula for nation-building purposes, promoting a concept of national identity relying increasingly on heroes, golden eras and national enemies, tightly linked to a Burman historical perspective (Salem-Gervais & Metro 2012).

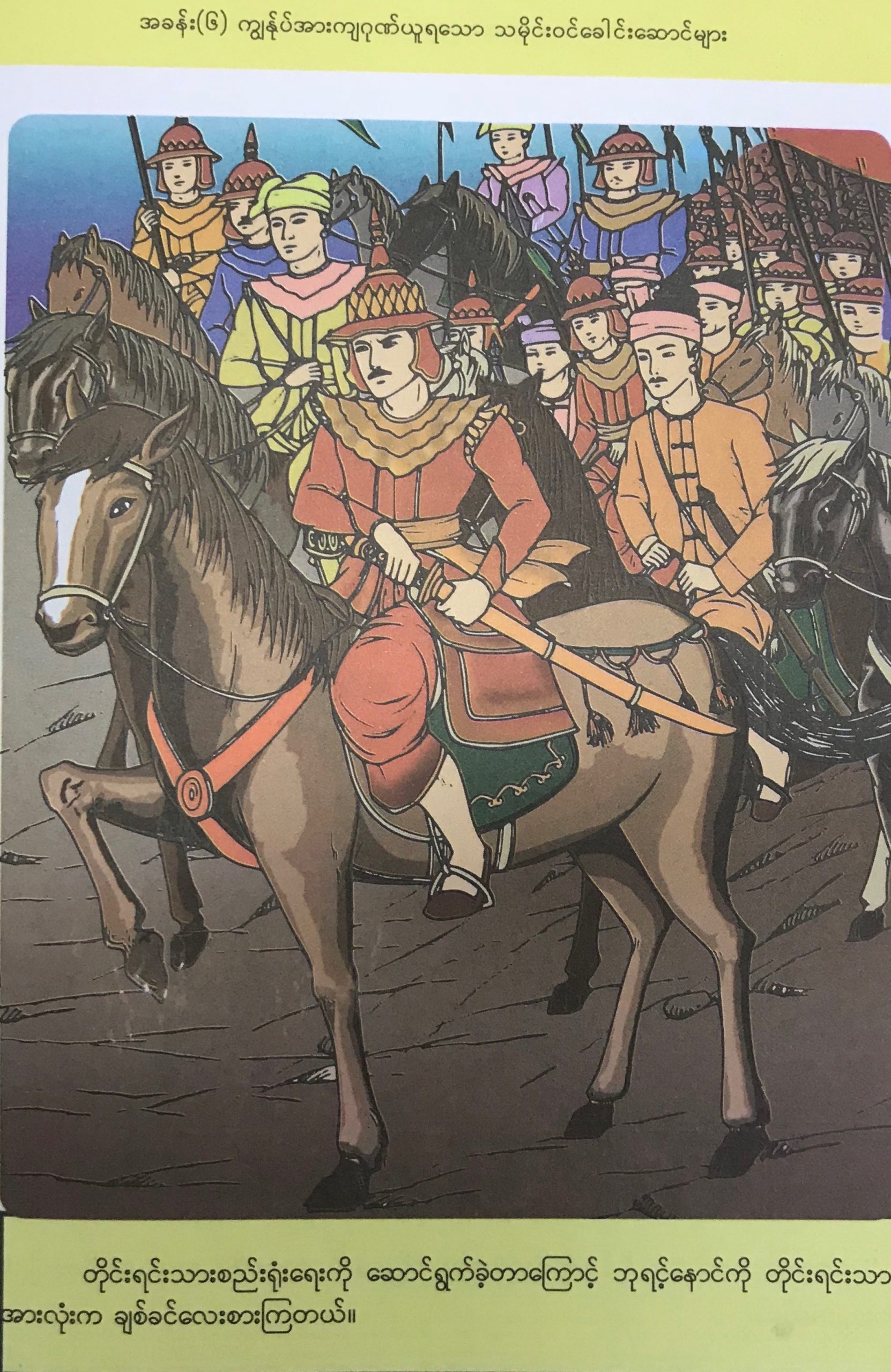

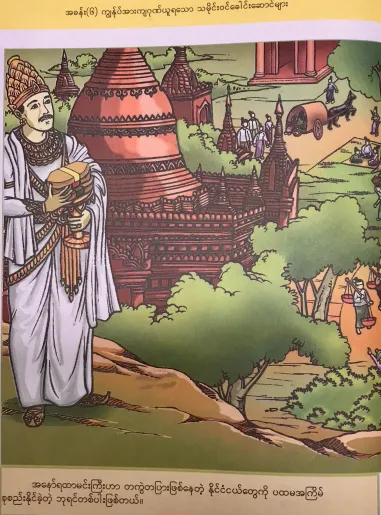

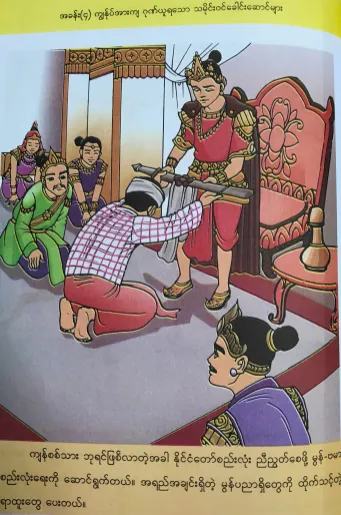

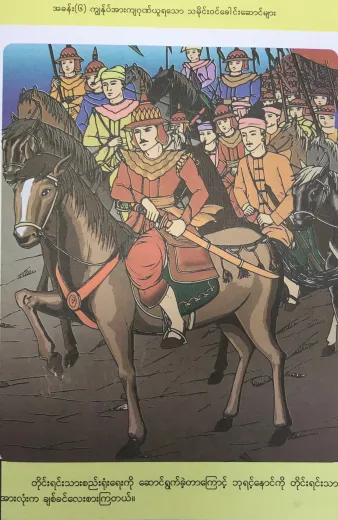

Famously, under previous military regimes, the successive historiography of three great kings (usually Anawrahta, Bayinnaung and Alaungphaya) presented them as the “unifiers” of what would become Burma/Myanmar, and have featured prominently in the textbooks (and elsewhere), with their successive empires presented as early forms of today’s Union. A number of EBEPs, often linked to ethnic armed groups, have done exactly the same thing in their respective education systems, indoctrinating their children with their own heroes, enemies and golden eras. Unsurprisingly, these visions of the past are totally antagonistic to one another; one camp’s heroes are often precisely the other camp’s villains (Salem-Gervais & Metro 2012).

The central role of education in nation-building (Walton 2018), and the necessity to promote a conflict-sensitive curriculum, has often been pointed-out. However, so far, as the new national primary curricula is being released year by year and grade by grade, things haven’t really changed when it comes to history (new textbooks are only available up to Grade 2 at the time of writing). While, overall, the new national curriculum seems to be an improvement, both in terms of visual attractiveness and the means by which it might stimulate children’s curiosity and autonomy, the changes in its history section are rather cosmetic.

The great kings and heroes, whom the children used to be introduced to only in Grade 4, are now introduced in the (new) Grade 1, in a much more attractive, children’s storybook style (see illustrations). However, the core narrative conveyed by these textbooks remains very similar: great soldier-kings using their swords, brains and goodwill to unify the ethnic nationalities/national races (tain’yintha) within their empires. One of the very few noticeable changes in that regard is the suppression of the honorific taw and kyi, after the names of the First, Second and Third “Myanmar Empires.”[1]

Parallel to this, as mentioned in Part 1, current drafts of the National Framework for Local Curricula, which are still in the early stages of development, make provisions for ethnic histories and cultures to be taught in government schools, alongside ethnic languages. One selected option seems to be to draft a textbook for each state/regions, which could be taught as part of the local curriculum, and featuring consensus-based general knowledge about the states and regions’ geography, history, culture and various characteristics.

Hopefully, practical meetings and discussions between the stakeholders, including various levels of the local MoE administration, the Regional Minister of Social Affairs, Ethnic Affairs Ministers, local scholars, UNICEF, and LCC members, will generate innovative and workable consensus, in what could be a contentious process.

Indeed, early versions of the local curriculum guidelines call for the choice of local “role-model personalities” (deithaatwin:shi sanbjapou’goumja:). This approach, just like in the above-mentioned history section of the new national curriculum, does not seem to be a departure from the old-school “national heroes”, which in Myanmar can be traced back to colonial and subsequent National Schools textbooks of the 1920’s and 1930’s, with their Myanmar Heroes (U Po Kya 1927, U Thein Maung 1933, Salem-Gervais 2013).

Used all around the world during the late 19th and the 20th century—France, my country, certainly being no exception—to inspire pride and national consciousness in the youth, this old-school “heroes approach” in the national narrative may not be best adapted to the reality of 2018, when social media in Myanmar is such a volatile and contentious space of public discussion. In a country where naming a bridge has been a source of controversy, and where the figure of General Aung San—who used to be as close as it gets to a common denominator, when it comes to national historical symbols—is now the object of staunch opposition, this approach seems not only sterile, but potentially dangerous.

Myanmar has been through many conflicts, within which identity and ethnicity has been and remains a critical component. Going down the road of finding–as if it was a zero-sum game–on the one hand, national unifier-heroes, and on the other hand, local heroes for every ethnic group, may not be the best long-term approach to promote peace through education. With such a complex political history, perceptions of the past are bound to be antagonistic; as mentioned previously, one group’s hero is the other’s villain, and new heroes will be resuscitated, or invented, just to fill the gaps, potentially fueling more controversies.

Current discussions around the development of the local curriculum suggest that some states have already abandoned the heroes approach, perhaps after failing to reach consensus, and several education experts involved in the process seem to be very well aware of the dangers of this arguably outdated nation-building strategy.

New approaches must then be found so that laudable efforts to maintain ethnic cultures and histories do not end up constituting a burden to the future of the country. Encouraging students to take a step back from multiple nationalist projects, precisely by deconstructing the fabrication of heroes throughout the country’s history, could contribute to a way past the deadlock. As initiated by Metro, using primary sources (rather than the classic readers/pha sa), and teaching (at higher level of schooling) that history is not necessarily about who arrived first, whose ancestors were the bravest during wars, and who teaches “true” or “false” history, could be helpful. Rather, explaining how different perceptions of a particular event or character can be developed, and helping students to understand critically and explain those different perspectives, could be a way to further diminish ethnic tensions and mistrust.

The aim of this three-part series is certainly not to scare away from, or to “impossibilize” (Lo Bianco 2013), the teaching of ethnic cultures, histories, languages and MTBE altogether. Creating or strengthening bridges between the already-existing, de facto MTBE systems of some of the EBEPs and the national education system is certainly liable to have important political and educational benefits. The (re)introduction of ethnic languages, as subjects, in government schools, which has been underway during the last few years, is also a very welcome development. Current efforts to improve the status of ethnic language teachers should be supported as part of the decentralizing of this activity to states and regions, and developing local curriculums. The prospects of support to the LCC by the Ministry of Ethnic Affairs and the states and regions could also be very good news. Finally, MTBE is already used, and should be encouraged, in pre-schools. At that level, where education is largely disconnected from any written form, ethnic languages are de facto more “classroom languages” (as stated in the Education law, see Part 2), than mediums of instruction. As such, their usage remains informal, they are less tightly linked to particular senses of identity, and are thus much less likely to be objects of contention in local politics.

According to an overwhelming majority of the interviews conducted for this research, a central issue in the education of ethnic minorities at the primary level, is the lack of local teachers. UNICEF estimates that 70% of teachers in ethnic areas cannot speak local languages (Jolliffe & Speers Mears 2016). This situation is due to the lower performance of minority students due to the language barrier, but also to specific perceptions of the State and the pull of economic opportunities, which often draw minority graduates away from civil servant positions and their unattractive salaries. The MoE’s teacher assignment policy seems to be slightly shifting in order to address this issue, and a very inspiring initiative has been recently set up in the region administrated by the Pa-O National Organization, in collaboration with the MoE, in order to train more local teachers (Lall 2016). However, the shortage remains, and finding sensible ways to encourage minority graduates to become in-service government teachers (an explicit goal in the NLD manifesto), is liable to have enormous benefits. Not only would it greatly facilitate the teaching of ethnic languages as subjects, with in-service teachers receiving “bonuses” on top of their salaries to teach them, but it would also contribute to reducing language barriers. Indeed, only those local teachers are able to use local languages as “classroom languages”, to explain the national curriculum, in order to improve the general quality of education provided in ethnic minority areas. On the long term, it is also an absolute prerequisite for any perspective of a functional MTB-MLE system.

However, overly-ambitious projects to decentralize language-in-education policy, as well as an emphasis on both Burman-centric history and the histories of ethnic minorities, could face challenges that may prove impossible to overcome, and become bones of contention rather than solutions to the country’s educational and political problems. As described throughout this series, the more ambitious the policy, the higher the stakes, and the more complex and uneven socio-linguistic situations will continue to be forced into discrete ethno-linguistic “boxes” that are, more often than not, very contentious.

Despite the wide consensus on the educational benefits of MTBE, several authors describe the multiples challenges which it may confront in the real world (see a synthesis in Metro 2018). While limitations of financial, human and pedagogical resources constitute a central concern, MTBE doesn’t always correspond to parental demand, and its educational outcomes are sometimes questioned (Tsung & Cruikshank, 2009). Some authors also point towards “classroom language” (code-switching) solutions when MTBE is not (yet) feasible (Gotosa, Rwodzi, Mhlanga 2013). Others, like Gupta (1997) go as far as to state that, in some cases, MTBE “may not be desirable”, in particular in multilingual settings, where identifying a single mother-tongue can be difficult, and in situations where it is likely to carry “social and ethnic divisiveness”.

The fact that in some regions, MTBE may actually be possible to set up in government schools, can be perceived in different ways. Certainly, in some specific places, MTBE could be beneficial, relatively consensual, and the challenges in setting it up could be possible to overcome. However, when designing a national or state/region level language-in-education policy, those locally non-problematic examples may prompt other actors to push for MTBE elsewhere—putting educational arguments at the forefront—where ethno-linguistic complexity and political sensitivities are much more important. Does aiming for a “hybrid” system amount to opening a Pandora’s box? It is a complex question, which is certainly open for discussion.

In any case, Myanmar presents arguably all the characteristics which make this type of language-in-education policy particularly challenging: great ethno-linguistic complexity, an extremely politicized conception of ethnicity entrenched throughout decades of conflict, and very limited resources available to every sector, including education. As much as a MTB-MLE national framework is an inspiring long-term goal, rushing it could also be hazardous. For the foreseeable future, focusing on implementing the teaching of ethnic languages as subjects in government schools throughout the country as part of the local curriculum, and making sure local teachers able to use local languages as “classroom languages” are available is already a challenging prospect; waiting for feedback on this process will help to better understand the practical challenges and their magnitude.

Needless to say, it is for the people of Myanmar to answer these complicated questions. I am and will remain an outsider, and my perspective is, admittedly, influenced by a western, French for that matter, political culture.

This research is also influenced by yearly fieldwork (over the period 2008-2018) conducted primarily (but not only) in Shan State, a region in which linguistic, historical and political issues are particularly complex and sensitive. Mon State, for instance, may present a somewhat less intricate socio-linguistic patchwork, but it seems to be the exception rather than the rule.

In any case, this series aims to encourage and participate in constructive debates on language-in-education policies in Myanmar, focusing on practical issues and their consequences, in order to contribute to the framing of a language-in-education policy that helps to preserve linguistic and cultural diversity, while bringing educational and political benefits for the future of the country.

Nicolas Salem-Gervais is a Maitre de conférence at the Burmese language section, South East Asia Department of Institut National des Langue et Civilisations Orientales (INALCO) in Paris, and is affiliated to Centre Asie du Sud-Est (CASE). Since 2007, his research has been dealing with various aspects of education and nation-building in Myanmar.

Notes

References

Like This Article

September 16, 2024

June 18, 2024

December 27, 2023

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023