Nicolas Salem-Gervais, on the challenges to ambitious language-in-education policies in Myanmar.

This is Part two of a three-part series – which forms a much shorter and more opinion-based version of an upcoming academic work (Salem-Gervais 2019) – aimed at offering a new perspective, and stimulating constructive debates, on several aspects of the representation of ethnic identities in Myanmar’s national education system, especially questions of languages.

In parallel with developments regarding the teaching of ethnic languages as subjects (see Part 1), several organizations campaigning in the fields of education and ethnic rights, most prominently the National Network for Education Reform (NNER) and the Ethnic Nationalities Affairs Center (ENAC), as well as scholars (Lall & South 2016), have called for a much deeper shift in Myanmar’s language-in-education policy: namely, implementing mother-tongue based multilingual education (MTB-MLE) throughout the country. In contrast to the simple teaching of ethnic languages as subjects, the basic principle of an MTB-MLE system is to offer a transition in the medium of instruction, usually throughout primary cycle, from the local language (L1), to the national language (L2), with often the introduction of an international language (L3). Only a limited number of actors today contest the idea that Burmese would be the L2 (and English the L3).

As of today, as stated in the 2015 amendment to the 2014 Education Law as well as in the 2016 National Education Strategic Plan (NESP), aside from their teaching as subjects, ethnic languages can be used as “classroom languages.” While this concept doesn’t seem to be very well defined internationally, its meaning in Myanmar now seems fairly clear, and does help underline a critical issue in the education process of ethnic minorities in government schools, namely the lack of local teachers (see Part 3). Using ethnic languages as “classroom languages” means using local languages, when necessary, to explain the national curriculum, which remains in Burmese. “Classroom language” thus seems to refer to a form of “code switching” and should not be confused with “medium of instruction.” The first is informal and oral while the second involves the whole curriculum.

While the concept of MTB-MLE, as such, is more recent, demands to use mother tongues as mediums of instruction are not new in Myanmar. Interestingly, in the 1920s and 1930s, Burmese nationalists invoked the idea that being educated in a language other than a child’s mother tongue could hamper their linguistic and intellectual development. This claim paved the way for the “national schools,” an education system in which Burmese language, history, and other components of Burman identity were prioritized (Than Htut 2005). After independence, the Shan State government, largely composed of sawbwas (local rulers) and ethnic elites striving to mobilize a Shan nation, invoked similar arguments to support the idea that Shan should be the medium of instruction for the whole of Shan State (Sai Kham Mong 2004).

And from a strictly educational perspective, starting education in one’s mother tongue certainly makes sense. The benefits of this approach are very well documented; if well implemented, such a system is likely to improve children’s command not only of their first language (L1), but also of the national language (L2) and possibly any other language they learn, while improving overall educational achievements. This type of system is also likely to be more effective than the mere teaching of ethnic languages as subjects, when it comes to maintaining ethnic languages and cultures.

Maybe even more importantly in the case of Myanmar, from a political perspective, this transition from the local to the national language certainly gives a sense of a “federalist” education, which is thought could play a potentially important role in “national reconciliation.” More specifically, such a system could simplify bridging the gap between Ethnic Basic Education Providers (EBEP, the New Mon State Party education model being the most aligned with international MTBE models) and government schools in ethnic minority areas.

Demands for MTB-MLE are also often framed in terms of “language rights” following articles 13 and 14 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which Myanmar signed in 2007, and which states:

“(…) States shall, in conjunction with indigenous peoples, take effective measures, in order for indigenous individuals, particularly children, including those living outside their communities, to have access, when possible, to an education in their own culture and provided in their own language”

In this context, a number of challenges need to be clearly identified, in order to set up a realistic language-in-education policy that could benefit the country, both from an educational and a political perspective, and not risk becoming a bone of contention in local and national level politics. The aim of the following sections is certainly not to discourage the use of ethnic languages in education in Myanmar, but rather, to stimulate constructive debates on these complex issues, some of which are rarely thoroughly discussed.

Unsurprisingly, the 110+ languages spoken throughout the country, which have influenced each other in multiple ways throughout history (on the case of Shan see Jenny 2016 in McCormick 2016), represent a variety of socio-linguistic situations:

While this type of complexity is not uncommon in Asia and throughout the world, ethnicity, subsequent to the equation between language and the concept of race in the colonial context in Burma (McCormick 2016), has been politicized to a great extent in Myanmar (Taylor 2005). Given this context of complexity and politicization, there is, for almost every group, on different scales, in different fashions and to different extents, the following tension. On the one hand, there is a desire to have a common language, a common script, and a standardized orthography, in order to strengthen what is perceived as a group and to give more political weight to the associated language. Projects involving the creation or the strengthening of a common language/script are numerous, and certainly not new in Myanmar ethnic politics. However, on the other hand, when it comes to agreeing on the terms of a particular linguistic unity, local forces linked to subgroups tend to mobilize to defend their particularism: one particular language, one particular dialect, one particular script. Each of these demands is arguably as legitimate as the next, which usually makes finding a linguistic compromise extremely challenging.

Numerous local examples—each one very specific—could illustrate this point: some Kachins may see Jingphaw as the common language of the Kachins groups, that should be promoted for all in education, whiles other may have different views; the Shans and their numerous scripts often have a hard time agreeing on a standardization of the script linked to Tai Long, which serves as a kind of Shan lingua franca, and producing common language textbooks; the Pa-O seem to have abandoned altogether the idea of having a common script for Northern Pa-O of Shan State and Southern Pa-O, primarily used in Mon State (see illustrations below).

Following language-in-education developments since 2012, the Palaungs, who have had language unification projects for decades, are also in the process of creating a common language, out of the six main, mutually hardly intelligible, Palaung languages. But multiple (Tai Khuen/Burmese-based) script issues remain, consensus is hard to reach, and giving actual life to what could be called a “test-tube language” may prove challenging (on these questions see Kojima 2016, Badenoch 2016, Weymuth 2016). Constituting a comprehensive list of these language and identity complexities across the Union of Myanmar is of course very challenging, and certainly beyond the scope of these posts.[1]

In a country in which ethnicity continues to be politicized (and performed) to a great extent (Egreteau 2018), those issues are of course not merely linguistic. All those particular languages, dialects and scripts, are always linked to different conceptions of identity, historical narratives, religious affiliations and political projects, which are, often, constructed in opposition to one another. They are also linked to specific actors: ethnic political parties, armed groups, specific local scholars and leaders, and local language and literacy committees, amongst others. The Akhas of eastern Shan State, for instance, currently use two different “common” scripts, the United Akha Orthography (created in 2004) and the Common Akha Orthography (created in 2008), each corresponding to different political projects, with religious and transnational implications.

In fact, not only is consensus hard to reach, but language and identity complexity is arguably increasing, or at least becoming more prominent in local politics, in the post-dictatorship context, and with the renewed perspective of using ethnic languages in education. New Literature and Culture Committees (LCC) have been appearing over the last decade and scripts are created yearly, with the stated aim to help maintain local languages and cultures and facilitate the education process. But, inevitably, these linguistic endeavors are also linked to specific groups or subgroups, specific actors and their specific political projects of mobilization of a particular identity. They are always defined in contrast to other, neighboring or encompassing political projects, sometimes even aiming to “purify” their languages by creating words to replace loanwords borrowed from other languages which are, or have been, influencing their own (Müller 2016).

Dissent over language issues can sometimes appear where it is the least expected: famously, the different branches of the Danu LCC (and their Facebook supporters) have been divided between the “pro-” and the “anti-” Danu script, created in 2014 (see illustrations), despite their language being relatively similar to standard Burmese.

Some of these issues will be settled, new ones might appear, and some may simply have no solution. These questions are in some instances extremely divisive and will be used for mobilization in local politics. In this context, the more ambitious the language-in-education policy, the higher the stakes, the greater the risks and the greater potential magnitude of disputes. Nearly all the Myanmar education specialists I have interviewed over the years, including LCC representatives (primarily in Shan State), seem to have a clear understanding of this challenge.

Which language should be taught in which school? And who decides? With decentralization, states and regions are starting to play roles in education, and may increasingly be in charge of these questions. There have been suggestions that recognizing as official the “main” languages of the relevant states in public administration, justice and schooling could be an option (Lall & South 2016, ENAC 2018). However—and regardless of how democratic these choices could be—determining which languages get to be “main” or not is likely to be extremely contentious in some cases, and adopting official languages for each state to be used in primary education often appears inappropriate, both from a political and an educational standpoint. Moreover, in many instances, these choices will not be any easier at the lower levels of administration, such as districts or townships. Only the school level thus appears able to make contextually relevant decisions about the appropriateness of a given language of instruction based on the local student body.

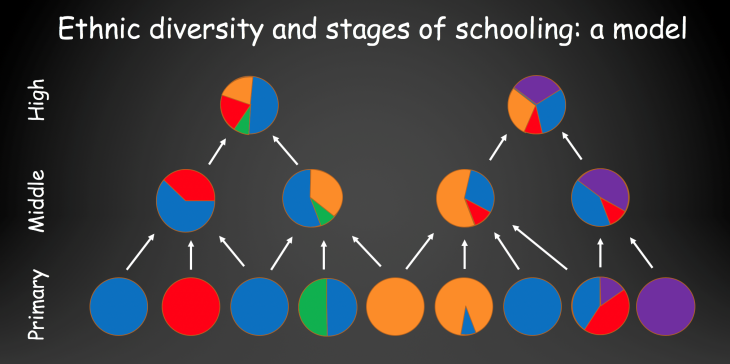

Unlike primary schools in ethnic rural regions, which tend to be in villages and are more ethnically homogenous, middle and high schools attract children from larger areas and are often more diverse (see illustration). When it comes to teaching ethnic languages in the latter, even as subjects—as suggested in the current drafts of the local curriculum guidelines—the challenges will be twofold: 1) some languages are far from being ready to be taught at that level, and 2) greater ethnic heterogeneity may be an obstacle to making the languages of all the ethnic groups attending a particular school, available as taught classes in that school.

At the primary level, despite a lack of language mapping data, which would allow us to assess the level of complexity that needs addressing, anecdotal evidence (collected through interviews, mostly in Shan state) suggests that, overall, 70% to 80% of schools are somewhat ethnically homogenous. This, generally speaking, could be good news for the teaching of ethnic languages, aligning with MTBE models, and making logistics more manageable.

However, there will still be some very difficult decisions to make in the remaining schools, where there are children with different mother tongues (in specific regions, like Naga-populated areas for example, these situations seem to be the norm rather the exception). Should children be separated in order to form linguistically homogenous schools? Should the schools be split in two or more groups for instruction? In contrast to informal daily multilingualism, which has been the norm in the country and region (Badenoch 2016), these options, arguably leading to a transformation of primary education into another channel of “discretization” according to ethnic identity throughout the whole country, are likely to have political consequences, since it could amount to de facto segregation. These options also have financial implications, since they involve an increase in the number of classes, and teacher’s salaries represent the lion’s share of the education budget.

In these complicated cases, should Burmese, or a language well understood by all (if there is any) be used as the medium of instruction? Given the sensitivity of ethnicity-related issues and the tendency towards divisiveness in Burmese politics, the actual decision-making or even the creation of guidelines to help settle specific cases, within a MTB-MLE national/state and region framework, is likely to be very contentious in some instances. Decentralization and democracy, while essential to the country’s political and educational future, may well prove not to be panaceas, especially in a context of very limited resources and local capacities (Minoletti 2016).

In Southern Shan State, small-scale controversies have reportedly already occurred, during meetings, between representatives of ethnic groups that have a history of fighting and distrust, over the question of which language should or should not be available in a specific school (as an optional subject and out of school hours). Here again, the more ambitious the language-in-education policy, the higher the stakes behind those complex and sensitive issues. In some places, rushing a MTB-MLE framework could thus prove counterproductive to the intended peace-building aims of education.

Some other challenges are relatively well known and documented, including a lack of financial, human and pedagogical resources, as well as limited capacities at different levels of administration, especially with the states and regions emerging as local education decision-makers. But those issues, as such, could certainly be addressed if there is a long-term political will to do so.

Another question, not to be overlooked in the introduction of minority languages in formal education, is the interest of ethnic minority parents and children themselves, who often see languages such as Burmese, English, or those of neighboring countries (especially Chinese and Thai) as keys to modernity and economic opportunity. Attitudes vary widely from place to place, even family to family, if not from one child to the next. The largest gap is between rural and urban populations, the latter much less likely to need or want an education in a local language. However, those voices, which are less likely to mobilize on any political scene, are rarely heard, and this can produce a somewhat distorted picture of a complex and heterogeneous reality. Understanding this heterogeneity in enthusiasm, which often contrasts with political discourses, is thus critical to developing a local-context sensitive language-in-education policy.

The fact that—when properly implemented—MTBE effectively leads to a better command of the national language at the end of a full schooling cycle, should also be weighed against very high drop-out rates in ethnic minority and rural areas. Would this situation imply that a significant number of ethnic minority children might, in practice, receive little education in the national language (depending on the particular MTBE model used)? A well-functioning MTBE system would contribute significantly to reducing drop-outs (and again, ultimately, lead to a better command of Burmese), but assessing the overall extent of that benefit seems difficult, since it would depend also on many other local economic and social variables.

In situations where those benefits of MTBE do not materialize, a lack of Burmese language skills at the end of schooling may have consequences, both on a political level, in the sense of belonging to the Union, and on an individual level, namely the impossibility of interacting with Burmese speakers, including civil servants, and difficulties in accessing the vast quantity of information produced in that language. Many speakers of languages such as Akha, Lahu, Pa-O, and to a lesser extent, Shan, also report that discussing certain topics in their mother tongue can be challenging, either because of their own limited skills, or because of the often narrower scope of these languages compared to more developed and standardized national languages, such as Burmese, Thai or Chinese. In that regard, several interviewees belonging to the Literature and Culture Committees (LCC) of these ethnic groups, clearly expressed that they want to find solutions allowing them to preserve—and even further develop—their respective languages, but without “sacrificing” (sic.) the future prospects of their youth. Certainly, a well-functioning MTB-MLE system could allow them to conciliate these objectives, but local realities and perceptions could constitute important challenges in practice.

Finally, an issue regarding MTBE in the specific political context of Myanmar, is that many actors (including what was known as the Ma Ba Tha and an education advisor to President Thein Sein), when hearing “mother-tongue,” see the prospect of having “non-indigenous” languages (such as Chinese, Nepali or Rohingya) taught in government schools in certain parts of the country. While the NNER has made clear that whatever language is relevant should be taught, other actors have used this argument to scare policymakers away from MTBE altogether, or at least make sure that only the languages of officially-recognized indigenous ethnicities (tàin’yìnthà in Burmese) are taught. Many ethnic educators would actually agree with limiting the use of MTBE (or even the use of “classroom languages”) to official ethnicities, despite basing their arguments for its use on its importance for educational outcomes.

Despite facing a number of challenges that are beyond the scope of this paper, the “Mon model”, which is often presented, or discussed, as a potential inspiration for the rest of Myanmar when it comes to MTBE prospects (Rinehart 2016, Lall & South 2016, ENAC 2018), is certainly remarkable. The Mon National Education Committee (MNEC) is the executive body of the education department of an ethnic armed group, the New Mon State Party (NMSP). After signing a cease-fire agreement in 1995, they made the choice of an education model of “federalist” inspiration (Lall & South 2012). This model indeed provides a transition from a Mon language curriculum to the national curriculum, throughout primary, middle and high schools levels, in a fashion that is very much aligned with international MTB-MLE models.

Using this model as an inspiration for other EBEPs may be challenging, in a context of conflict, generalized distrust, linguistic challenges, diversity of language-in-education models, and because of the underlying conceptions different groups have regarding their particular identity and the positioning of that identity vis a vis the Union of Myanmar. Nevertheless, it is certainly an inspiring model to aim for in the perspective of integrating EBEPs in a national education framework.

However, the idea that the Mon National Schools (rather than the “mixed schools” of the MNEC, in which Mon language, culture and history are only taught as subjects, in a fashion which seems to align with the local curriculum prospects, see Part 1) could constitute an inspiration for a MTB-MLE policy in government schools throughout the whole country may be problematic. This vision may overlook the fact that the MNEC schools and the Mons in general represent a unique socio-linguistic situation, many aspects of which cannot be replicated through language policy. These characteristics include: a relative linguistic homogeneity, a somewhat “compact” population setting, a very ancient written tradition, an overall very positive attitude towards their own language, a strong mobilization for mother-tongue education over the last few decades, and the presence of a significant number of Mon teachers in government schools.

The Mon example thus appears to be, by far, the least complicated case across the Union when it comes to setting up an MTB education system. While other groups, which present a great variety of socio-linguistic situations, will certainly find valuable inspiration in that example, all the LCC and various education actors that I have interviewed in Shan state are aware of the comparative advantages of the Mon situation, and of the impossibility to replicate some of its characteristics (see conclusion in Part 3).

Nicolas Salem-Gervais is a Maitre de conférence at the Burmese language section, South East Asia Department of Institut National des Langue et Civilisations Orientales (INALCO) in Paris, and is affiliated to Centre Asie du Sud-Est (CASE). Since 2007, his research has been dealing with various aspects of education and nation-building in Myanmar.

Like This Article

September 16, 2024

June 18, 2024

March 06, 2024

February 22, 2024