Bobby Anderson explores fundamental—and often, incompatible—differences in perception between Myanmar’s military, civilian, and insurgent authorities.

This post is part of Tea Circle’s “2018 Year in Review” series, which looks back at developments in different fields over the last year.

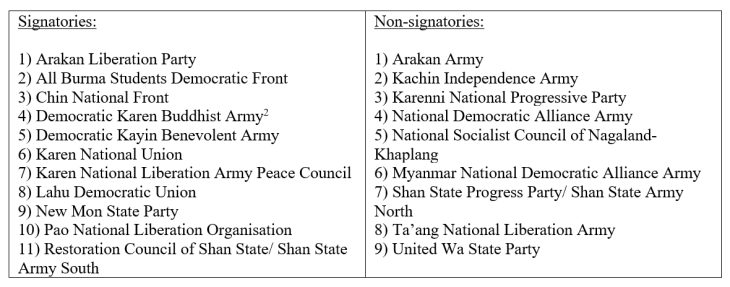

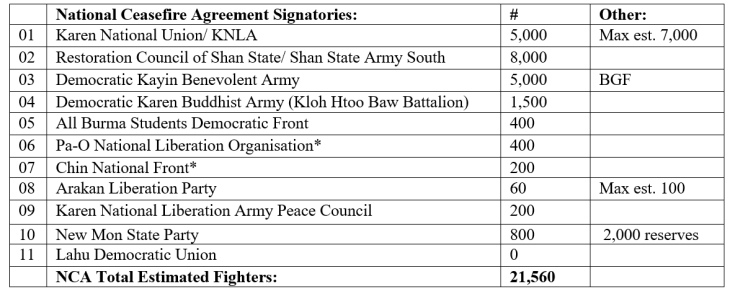

Let’s begin with the insurgent groups and their fighters. Measuring NCA participation by the number of groups rather than the number of fighters within groups produces unexpectedly rosy results, with eleven signatories and nine non-signatories:

Not many of the signatory groups actually possess recent combat experience. The non-signatories have it in spades.

The Karen National Union and the Restoration Council of Shan State—the main actors that legitimize the NCA—have it. The New Mon State Party, the Democratic Kayin Benevolent Army, and the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army also merit mention. The other NCA groups are no longer significant, and a few are historical relics; they have been described by Bertil Lintner as NGOs rather than EAOs.

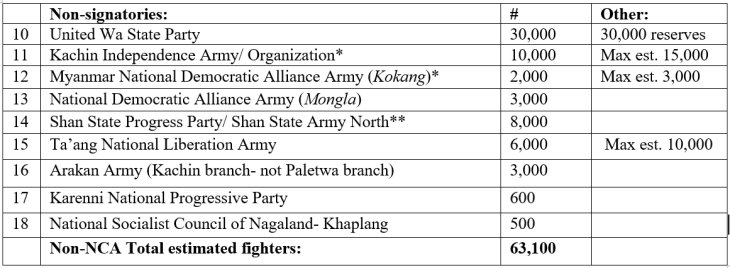

Of the non-signatories, the military refuses to acknowledge the legitimacy of many of the groups it is most actively fighting: namely, three of the four entities which constitute the Northern Alliance, which launched an offensive against the Tatmadaw in late 2016 in northern Shan State. The NA is comprised of the Arakan Army or AA, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army or MNDAA, the TNLA, and two brigades from the Kachin Independence Army or KIA. Even if the former three wished to sign the NCA, the Tatmadaw wouldn’t let them. The three contain a minimum of 11,000 experienced fighters: adding the KIA to the total brings it to a minimum of 21,000.

The Northern Alliance, for its part, now falls under the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultation Committee, or FPNCC, a negotiating block created and led by the United Wa State Party or UWSP- the largest, best armed, and most cohesive EAO in the country. The Shan State Progress Party and the National Democratic Alliance Army- a separate group from the MNDAA- are also members. Unlike many an EAO alliance, the FPNCC is proving more durable, and at present it contains, including reserves, 92,000 fighters: the absolute majority of EAO fighters countrywide.

The NCA lacks substance if it lacks these groups and lacks the means by which to include them. Unable to recognize the elephant in the room, both the military and the civilian government refuse to negotiate with the FPNCC as a bloc. This is an inelegant attempt at “divide and rule”: the continued use of a playbook that has failed the state across the last half century.

The FPNCC, for its part, has suggested a new peace process beyond the confines of the NCA, which frustrated EAOs might embrace. They might force a different settlement.

EAOs want a political dialogue about the parameters of a federal state followed by security sector and constitutional reform, after which disarmament, demobilization and reintegration of EAOs (DDR) might occur. The Tatmadaw, fantastically, want EAO’s disarmament prior to political negotiations. This could also be described as “surrender”. The Tatmadaw make the same demand for the non-signatories it wages war against in the north. The civilian government supports their position. This is a complete non-starter, and reflective of a lack of sincerity, as well as a page from the above mentioned playbook. In 1981, talks between the KIA and the Tatmadaw fell apart when limited autonomy was rejected. 37 years on, the word federalism is used as a lure, but it is, so far, without substance. That a discussion around it has not even occurred since 2015 reflects an incompatibility of positions.

Besides federalism, the Tatmadaw demands that signatories acknowledge the 2008 Constitution, which formalized Tatmadaw embeddedness in the civilian government through control of the Ministries of Defense, Border Affairs, and interior/ home affairs; an allotted 25% of parliamentary seats that ensures veto power; and a defined right to seize control of, and disband, an elected civilian government. This obviously discourages EAO disarmament. The few powerful signatories engaged with the NCA with the implicit belief that the process might lead to the reform of that same Constitution. Few believe that this is now likely, especially after the murder of Ko Ni.

Whether the KNU will remain in the current NCA peace process is also an open question. Their acceptance of the agreement was also an acceptance that they would maintain their territories in the southeast, with no government or Tatmadaw encroachment without permission. But the Tatmadaw is extending roads into KNU territory in Papun, Kayin state, and fighting between the two is ongoing. The Tatmadaw’s claim that the roads they are extending will be for civilian, and not military, purposes, is disingenuous. Roads transport troops. The Tatmadaw is violating the NCA through these acts, for all EAOs to see, while paradoxically encouraging others to sign the same agreement they don’t abide by. If the KNU leaves the process, the process may well be over.

The FPNCC—the most powerful and significant non-state actor in the country—is implicitly backed by the most powerful state actor beyond Myanmar’s borders: China, which has emerged as the biggest non- Myanmar player in the peace process. Western groups, for their part, struggle to maintain relevance.

Times have changed since human waves of Chinese Red Guards overran Tatmadaw positions in Northern Shan State in 1968 and established the area as Communist Party of Burma or CPB stronghold. The CPB leadership’s declared support for China’s “Gang of Four” clique in the power struggle which occurred after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 backfired when Deng Xiaoping emerged victorious from that struggle: Chinese support to the CPB and other foreign revolutionaries waned as Deng implemented a benign foreign policy focused on trade. Across decades of sanctions, China provided an economic lifeline to the Tatmadaw that, through then-Military Intelligence chief Khin Nyunt, closely aligned itself with China’s civilian and military authorities. Factionalization within the Tatmadaw emerged from such alignment, and Khin Nyunt was arrested and jailed in 2004. His faction—and China’s intimate influence—was purged.

The Tatmadaw’s allowance of a shift to quasi-civilian government reflected in part the need to diversify foreign relationships, especially in the west. But from a low point of the halting, by then-President Thein Sein, of the US$3.6 billion Myitsone dam project in 2011, China has deepened connections and investments across the country, including the establishment of special economic zones, a port at Kyaukphyu, Rakhine state, and future pipelines from the Rakhine coast to Yunnan, reducing dependency on the straits of Malacca for oil and natural gas shipments. That pipeline is one reason of many that China needs calm on Yunnan’s western border, where the fighting between non-signatory EAOs and the Tatmadaw is heaviest.

Enter the FPNCC, which was created with China’s implicit support. It reflects, in part, recognition in China that the NCA is stalled and either needs a boost or a burial. The seriousness with which China takes its involvement is reflected in the appointment of the Special Envoy Sun Guoxiang: while the NLD finds itself in the position of untrusted mediator between the Tatmadaw and EAOs, Guoxiang successfully mediates between all three, and it was his diplomacy that led to FPNCC representatives attending the June 2017 Panglong conference, including guaranteeing the safety of the delegation. A consolidation of influence also occurred through the election, in January 2018, of a new KIA leader, N Ban La, who lacked the Christian-influenced sentimentality that past leaders had for the west, followed by that group’s membership in the bloc.

Bobby Anderson (gletkin@gmail.com) is a Myanmar-based Research Associate at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Like This Article

September 16, 2024

March 06, 2024

September 07, 2021

November 03, 2020

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023