Alex Aung Khant presents different approaches to public infrastructure projects.

In the coming years of Myanmar’s development, Yangon is poised to maintain both its position as the largest city and economic hub, and grow exponentially in size. Urban mobility and mass transportation in Yangon is already an unresolved problem, and is frequently reported as one of the top concerns of Yangon residents, as was also covered in the 2018 City Life Survey by the Asia Foundation.

In order to tackle this challenge, the Yangon City Development Committee (YCDC) and its development partner the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA), has outlined the development of an urban rail system as a key priority to improving urban public transportation as part of its “2040 Strategic Urban Development Plan of the Greater Yangon”. The Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is one of the larger, international development assistance partners working on Yangon on the topic of public transportation. Recent comments from officials of both JICA and YCDC point at 90% of the city’s occupants using public transportation, and agree that an urban rail system in Yangon will be costly but “critical to urban transport”.

In order to fulfill this key priority, the Yangon Regional Government (YRG) started in 2015 the Yangon Urban Mass Rapid Transit (YUMRT) project for the construction of an elevated sky-train. While this may very well be welcome news for Yangon residents, this 18 km long mega-project is estimated to cost billions of USD. This extremely costly endeavor is fully financed by Official Development Assistance (ODA) loans from JICA. With a project of this scale and the limited capacity of management and financing by the Yangon Regional Government, it brings about further questions on whether the project should be delegated to the central Union Government in Naypyidaw instead.

Looking to examples of the relations between the central government and urban authorities, and as exemplified by other ASEAN countries as presented below, this paper proposes the following indicators to assess the project:

These indicators were also used to analyze past examples of projects implemented at the regional level, such as the Yangon Bus System and Yangon School Bus Program, which are both noteworthy for their financial control and mismanagement. The indicators will also be used to examine whether centralizing management of a local transportation project from the national level poses a conflict of hierarchy and control from Naypyidaw over the Yangon Regional Government. The same indicators can also be applied to international examples to find similarities and differences in their experience of handling such projects.

37 combined interviews were also conducted during research in Yangon and via telephone in Naypyidaw between June and September of 2019. The interviews were targeted to civil servants from several ministries and departments, YCDC, Yangon regional ministers, Yangon region Members of Parliament, representatives from JICA, and public sector organizations such as the Yangon Heritage Trust and the Association of Myanmar Architects.

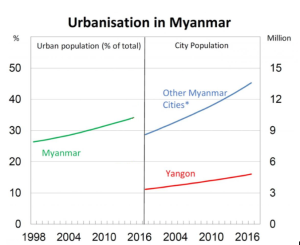

In recent years, Myanmar’s development has been marked by the growth of its cities, and increasing numbers of rural-to-urban migration in search of better opportunities. According to the 2014 census data, the 50 million people of Myanmar are split between 70% in rural areas, and 30% in urban areas. As the country moves towards development, urbanization and migration of the 35 million rural populace to urban areas can only be expected to increase in the coming years. World Bank data projects the Yangon population to double within the 20-year timeframe from 2000 to 2020, while other Myanmar cities are projected to see even greater urbanization due to internal migration.

With further urbanization, congestion and providing public transportation and mobility for the masses will become an even bigger challenge. Yangon region alone accounts for about 15% of the entire population of the country with 7.3 million people in the metropolitan area (city-proper populace is approximately 5.1 million). By 2030, this number is forecasted to grow to 10 million. No other city in the country currently has a scheduled public transportation system. Yangon alone is currently the only city to have a bus system, the Yangon Bus Service (YBS), and a colonial-era commuter rail network, the Yangon Circular Railway that was built under colonial rule in 1877. Another colonial-era tramway along Strand road was also briefly operational from 1906 to 1921, and efforts to revive it as recently as 2016 have all failed.

Rail-based transportation (tramways, elevated sky-trains, and underground metro trains), is considered one of the most efficient, effective, sustainable and timeproof types of mass public transportation for urban areas. The International Energy Agency of the OECD states that rail transportation is one of the most energy efficient modes of transport for freight and passengers, accounting for about 8% of the world’s passengers and 7% of global freight transport, while only consuming about 2% of global net transport energy demand. In 2016, over 75% of global passenger rail transport activity used electrical energy sources, making rail transport environmentally sustainable as well.

However, rail construction whether underground or tramway or elevated, is a very costly endeavor. In this City Lab article appropriately titled “Why $1 Billion Doesn’t Buy Much Transit Infrastructure Anymore”, the average cost of underground rail construction in continental Europe and Japan, considered global leaders in this aspect, is between $100 million per mile at the lowest end and $1 billion at the highest, while the ASEAN regional best Singapore’s latest Circle Line had a cost of over $200 million per mile.

Although indeed the project itself is at the city level, the scale of construction and costs of urban rail puts it on par with national level projects.

Most of Myanmar’s megadevelopment projects have taken place outside of urban metropolises and in more rural areas. The construction of large hydropower dams along several rivers such as the Yeywa dam 52 km from Mandalay, and trading ports in dedicated Special Economic Zones (SEZs) such as Thilawa SEZ 45 km from Yangon are all far removed from large cities. Being outside of urban areas makes these projects easier to manage by the relevant central Union government ministries at the National Level, and their nationwide impact (such as on trade and electricity) are far beyond the reach and impact of regional governments. Urban rail transportation, however, is only relevant at the city level, while still requiring significantly high costs.

4 Minutes To Read

October 4, 2017

Several other developing countries, including those in the South-East Asia region, have also faced similar challenges on their path towards development in their major cities, on balancing financial and political management capacity between overseeing it at the national level, and decentralizing to the sub-national level. The development of the Greater Kuala Lumpur MRT system since 2010, led by then-Prime Minister of Malaysia Najib Razak, is still troubled by financial and management problems to this day, and has also caused a dispute between the Finance Minister and the Works Minister.

Very recently, the first subway in Indonesia, the Jakarta Mass Rapid Transit, officially opened on the 24th March 2019. Despite Jakarta being one of the world’s largest urban metropolitan areas at close to 30 million inhabitants as well as Indonesia’s center of economics, culture and politics, it still took over 12 years for the project to yield results after having signed an ODA loan agreement with JICA for ¥747 Billion Yen, equivalent to USD 6.8 billion.

In 2007, JICA also signed an agreement with Vietnamese authorities for the construction of the first metro line in Ho Chi Minh City and in 2016, an ODA loan of USD 1.5 billion was extended to the project. Last November, the project took a different turn as the Japanese Ambassador to Vietnam threatened to stop construction works due to the city government’s late repayments. The project has since been thoroughly reviewed by the National Assembly of Vietnam and subsequently absorbed by the national government.

There are several sources of reliable and relevant references that can be drawn from across the South East Asia region on the same questions. Academic study on the topic, not limited to the case of Myanmar, has mainly been focused on the actual implementation process (usually going at length to examine public-private partnership (PPP) scenarios and factors of success and failure behind each model). This is very much the secondary part of developing projects, and the very first step of simply clarifying roles and responsibilities of which government agency, national or local, is to be responsible for such billion-dollar projects is not well studied.

Sharma (2012) examined the factors determining PPP in infrastructure for the period 1990-2008 for 22 developing countries primarily in South Asia, South East Asia and South America. The study observed that large size and relatively high-income markets enhance more PPP projects, as there is a robust private sector and a general will to participate in government development projects. However, the study did not examine at length the role of political factors and budget constraint as important factors.

Emirullah & Azam (2014) looked at the investment climates for PPPs, macroeconomic stability, political stability, the legal and regulatory environment, governance effectiveness, levels of corruption and market conditions for PPP. Their paper also concluded that government debt levels, GDP per capita, market capitalization of listed companies, governance effectiveness, regulatory quality, and control of corruption tend to have a positive impact on PPP arrangement in those countries.

The critical issue here, specifically in Myanmar, is that while there is certainly a robust private sector – with many large billion-dollar development conglomerates in the country (such as Asia World, Shwe Taung, Eden Group, Dagon Group, Max Myanmar, Htoo Group many of which were even involved in the construction of Naypyidaw) – political institutions in Myanmar are noticeably weak, and political power-sharing is even weaker with the country’s political decentralization still in its infancy. The OECD Framework for Infrastructure Governance fittingly states that “poor governance is a major reason why infrastructure projects often fail.”

This brings us no closer to clarifying which government level – national or regional – should direct and manage billion-dollar projects. If the national government at the ministerial level were to assume centralized direct control, that would overarch the regional government and diminish government decentralization. At the same time, if the Yangon Regional Government were to assume control, on the basis that the YUMRT project is limited within Yangon city limits and should therefore be under their control regardless of project size and budget, it would also overrule the national government and render governmental hierarchy obsolete. Any one person at the regional level, if in charge of a billion-dollar project, is quite likely to be in control of more money than anyone at the national level and could bring up a direct contradiction of power.

A brief overview of Myanmar’s previous development models shows us that large infrastructure projects were either taken on directly by the government via state-owned enterprises (SOEs) during the military regime, or via private business corporations that were tied either directly or indirectly to high-ranking individuals of the military commonly called “crony-businesses”.

There were also military enterprises which were under the Ministry of Defense that originally supplied goods and services for military operations, but later grew to manage a vast and diverse portfolio including gems, teak, food and beverage production, garments, construction, industrial materials and service sector businesses such as hotels and real estate. Known examples of existing military enterprises are the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd. (UMEH) and the Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC). In 2013, the UMEH was considered the biggest conglomerate in Myanmar with a registered capital of USD 1.4 billion.

In either of these three cases, the “developer” of the infrastructure project was either directly overseen by state-owned enterprises and military-enterprises or indirectly as a stakeholder through crony businesses, or as the national government itself. This meant that both financial control and management were taken at the highest level, and the sub-national governments simply had no say and acted only as the implementor of the national government’s decisions.

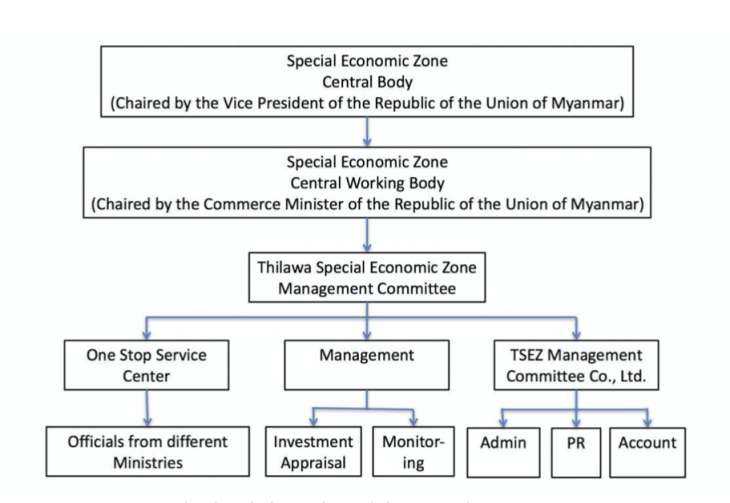

The constitutional change of 2008 also brought about the creation of the regional governments which are led by Chief Ministers, alongside regional parliaments and regional MPs. On paper, this should allow for greater decentralization for both political decision-making as well as fiscal control. Regional governments are delegated the responsibility of all development projects within their demarcations, except for SEZs which are coordinated by its own specific SEZ-Committee and governed by a special Myanmar Special Economic Zone Law.

A fitting example would be the Thilawa SEZ, lauded by the State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi herself, which was set up with government-to-government help from Japan, and governed by the Thilawa Committee. It is chaired by Deputy Union Minister of Planning and Finance U Set Aung, with Yangon Region Minister of Construction, Industry, Electricity and Transportation Daw Nilar Kyaw acting as Vice-Chair in a setup which has both Union and Regional representatives.

Larger development projects on the national level, such as the construction of large hydropower dams and inter-city railway projects, are also led by their own specific committees that bear a similar, top-down approach and involvement of the highest level of officials in the governing structure.

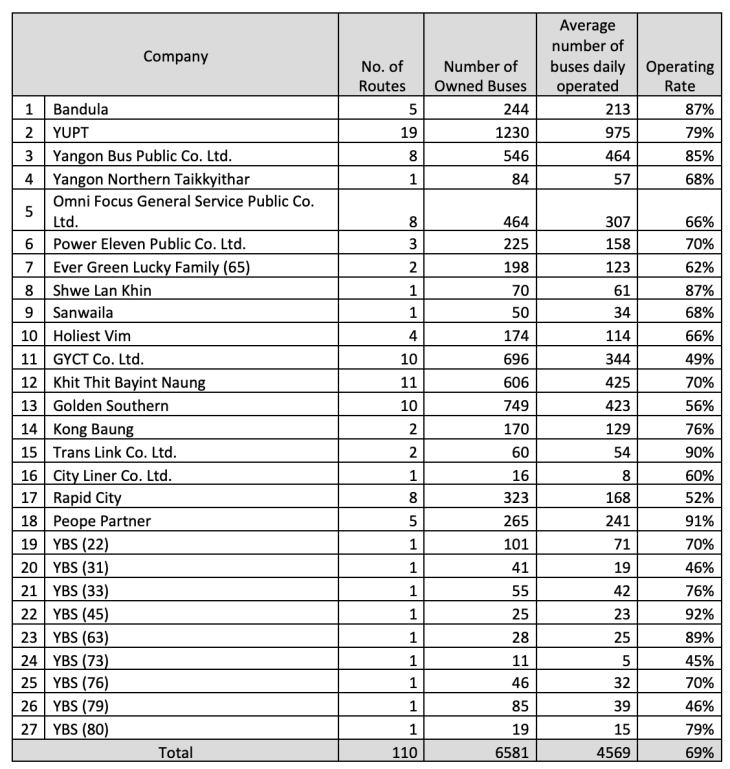

Regional development projects also typically follow a downsized version of this model, placing the Chief Minister of that region as the highest official at the top, and a mix of other regional ministers. The aforementioned public transport system of Yangon, the YBS, falls under the authority of Yangon Region Minister of Transportation Daw Nilar Kyaw (who also serves as Vice-Chair for the previous example of the Thilawa SEZ). While this greater level of political and fiscal decentralization should point towards a more efficient decision-making and leadership, in reality YBS is observed to suffer from a lack of sufficient authority and financial capacity.

Of the 27 individual bus operators inside the YBS conglomeration, problems have emerged especially from the presence of Omni Focus – a company led by the two grandsons of former dictator General Ne Win. Omni Focus took out a loan of 56 billion kyats (US$36.8 million) from AYA Bank in 2017 to buy 500 new buses. According to regional lawmaker U Kyaw Zeya, a member of the Yangon Regional Parliament’s Finance, Planning and Economy Committee, the loans were provided “because the regional government told the bank to do so.” To add more obscurity to this, there is no structured organizational chart of the YBS consortium (or at least it is not publicly available) because of internal struggles by Omni Focus to wholly take over the day-to-day operational control of YBS. Currently, loans have not been repaid to AYA bank and a legal case is being considered to resolve the scandal.

Without going too much further into detail, this YBS scandal proves that simply downsizing the model of development used at the national level cannot be applied effectively at the regional level.

The many nuances shared by other equally densely populated, developing countries in the region make South East Asian neighboring countries an appropriate reference in this study. However, it is also important to note that not all South East Asian references are relevant to the case of Yangon and Myanmar. Despite the many shared commonalities as per status of developing countries (former European colonies, proportionally similar urban populations, and even some shared government structures) the key difference is the economic power of other ASEAN countries.

As per the latest available statistics by the World Bank, Myanmar’s GDP in 2017 stood at 69.3 USD billion with a population of 53.3 million, while Malaysia had a GDP of 314.5 billion while only having a population of 31.6 million, with a difference of USD$1298 GDP per capita in Myanmar versus USD$9944 GDP per capita in Malaysia. The difference is thus just under five times more GDP in favor of Malaysia for about two-thirds of Myanmar’s population. (Just the state of Selangor in Malaysia alone has a GDP of about US$55.5 billion in 2015 with only 6.4 million population). If compared in terms of purchasing power parity between the two countries, the differences would be even larger.

As stated earlier, rail transportation projects are costly by default, but this stark economic disparity means that regional governments in Myanmar are not afforded the option to take on billion-dollar projects without considering the national impact. This therefore means that while regional governments in Myanmar are theoretically meant to have greater autonomy through political and financial decentralization, in practice the state of Myanmar’s economy puts a clear limit on their actual spending power. Regional governments in Myanmar do not have access to funds in the same way or capacity as their counterparts even in neighboring developing South East Asian countries.

Conversely, if we were to imagine a situation in which a regional government in Myanmar did indeed have the capacity to take on a multi-billion-dollar project, it also means that whichever official or authority that has assumed responsibility would automatically become responsible for quite possibly the largest project lump sum to date. Assuming that Yangon Region Minister Daw Nilar Kyaw was to be wholly put in charge of the USD 2-billion YUMRT project, it could also mean that she would be overseeing a single project worth about 3% of the entire national GDP, making her disproportionally powerful. In other words, if the regional authority is responsible for a project that involves more financing than the national authority, it could create an imbalance of power disparity, and inverse the political hierarchy.

Such scenarios point to a need for power-sharing and cooperation between regional and national government officials, much like the way in which SEZs are governed. Looking at examples of city-level megaprojects from across the region in South East Asia as described earlier in this report, there are cases where the national government intervenes and creates a hybrid system of cooperation between the national government and urban authorities, not unlike the SEZ administration system in Myanmar. Both the aforementioned Kuala Lumpur MRT and Jakarta MRT followed this model, and relied heavily on this national-urban cooperation.

In the course of the research, three main schools of thought regarding the management and financing of megaprojects in cities can be summarized. The first, more traditional argument is that the national government is the correct authority to handle such projects. This is for many reasons, primarily that accountability is often better handled at the national level and that due to the sheer size of the budget it has an impact on all taxpayers in the country. A practical shortcoming of this first method is that efficiency amongst government officials tend to decrease as the ranks increase. Union-level officials in Naypyidaw are famously overloaded with many different matters, and it has been reported that “the government lacks the ability to carry out reforms.”[1]

The second school of thought, which started becoming more popular since the early 1990s, is that sub-national governments and especially city governments perform much more efficiently and that they should maintain a level of autonomy in handling urban projects within city limits. This is supported by research in decentralization and deregulation of political control from the national government to the sub-national level. While in theory it may have its benefits, the main weakness of this second method is that sub-national governments often do not wield sufficient cohesive political power nor financial capacity in reality. These weaknesses are all the more profound in developing countries with weak institutions. Without accompanying gradual changes for good governance and best practices, this second method can overload sub-national governments beyond their capacities.

The third view can be considered as a hybrid of the first two and calls instead for the establishment of an independent project management body, joining both the national and city level authorities and forcing cooperation. This third method is however not as straightforward, as the composition of such bodies usually need to be based on additional, separate laws (not unlike the separate SEZ laws in Myanmar). It would mean the creation of a separate specialized entity, such as an urban transport service provider that is especially mandated to oversee the project from start to end. These entities usually take the form of a public-private partnership, under a consortium of both government control as well as either one or multiple private operators. Many examples exist in the region, such as the Bangkok Mass Transit System Public Company Limited in Thailand, the Prasarana Malaysia Berhad and the Konsortium Transnasional in Malaysia, and the TransJakarta and PT MRT Jakarta of Indonesia. Most of these consortiums are listed as public companies with shareholders and may also count the government itself as one of its majority shares. While these hybrid bodies also seem to be viable solutions, a shortcoming to this third view is that the creation of these bodies take the longest time in setting up their specific, hybridized legal structure.

Through our review of the SEZs and regional projects such as the YBS, Myanmar has some political autonomy in local government agencies. Chief Ministers are also well-placed to oversee regional development projects in the urban areas.

No Chief Minister has yet been put in charge of billion-dollar projects, and this lack of experience puts forward a new challenge in ensuring that there continues to be political autonomy to local government agencies when the size of the project increases. It should be noted however, that greater political autonomy to regional governments is not the requirement here. The YRG’s difficulty in dealing with the 27 YBS operators also shows us that greater autonomy does not necessarily warrant the success of a project.

In fact, giving further autonomy to hybrid bodies could be a better solution, involving some key national-level stakeholders to lend greater power. The involvement of officials from the Union government would also complement further political autonomy.

Though this has not been attempted in Myanmar, the inclusion of non-governmental academics and industry experts could also reinforce trust in this hybrid entity, as well as ensure the success of the project owing to the added working knowledge. Union officials can rely on these experts to verify the best practices of the project, and give more autonomy within the hybrid entity.

For this indicator, the aforementioned section on “Examples in South-East Asia” has already described the position in which Myanmar as a country is not easily afforded the option to take on billion-dollar projects without considering the national impact. The government has a clear limit on actual spending power and must carefully prioritize the many infrastructural needs in Myanmar. This means that the YRG has very limited financial capacity to begin with due to the country’s situation.

Despite being the authority in charge of urban areas, the YRG is only allocated MMK 77 billion (US$49.7 million) for fiscal 2019-2020. This pales in comparison to the gargantuan price tag of the 2 billion-dollar YUMRT project, and the financial management strains faced in the YBS project can only be expected to be exponentially higher. This adds a second reason to consider an alternative management entity to oversee large development projects that is not the YRG.

A combined assessment of these two indicators shows us that the Yangon Region authorities have a strong need for general capacity building, as well as intensive training and development of specialized technical skills (this includes all aspects of financing and managing mega-projects, ranging from administrative bookkeeping skills to highly specialized engineering skills).

This shortcoming does not however mean the end, on the contrary, it in fact opens up greater possibility (and need) to include external experts in the managing body. These experts would directly address all technical and specialized matters of mega-projects, providing reliability for the managing body. The capacity of authorities and general staff can also still be uplifted overtime through knowledge trickling down from the experts. This solution would be vastly faster than normal capacity building programs, or even intensive training, which would still take considerable time and investment. Including non-governmental experts in the managing body de facto would be a hybrid system.

In assessing this indicator, it was difficult to precisely weigh the overall perception of stakeholders, particularly of the government, by the media. The jailing of journalists under the current civilian created resentment against the ruling leadership. The wider media community therefore is largely, and at times overly, critical of every aspect of the ruling party. Having said that, the most notable example of the YRG’s financial mismanagement of the YBS are also yet another direct reflection of the lack of capacity as the majority stakeholder.

This indicator therefore shows us that, for various reasons as examined in this paper, both the national government and the regional governments in Myanmar are strongly not perceived to have the necessary capacity to handle future megaprojects. The evidence in reality also shows us that this perception is very true, at least for the time being. In lieu of this reason, it would leave out only a hybrid system which includes external experts as the only possibility.

Among the different viewpoints and nuances presented in this paper, there are nevertheless two main commonalities that are shared across all aforementioned examples, namely: 1) that the size of the project is in the billion-dollar plus tier, and 2) that the projects take place in urban areas traditionally governed by city-level or regional-level authorities (and to a much lesser degree by the national government).

While taking these two commonalities into account, it is also clear that in catching up with the world Myanmar needs to tackle and deliver on its infrastructural needs. Myanmar’s current situation – both economically as a developing country with financial limitations, and politically as a young and struggling democracy with weak institutions and vague structures – makes it difficult to identify the correct approach to financing and managing mega-development projects.

Almost all interviewees responded that there is no certainty in deciding whether the national or regional government is to take on megaprojects, meaning that neither of these two methods are realistic solutions. As per the discussions in this paper, the final conclusion is such that while a decentralized approach to financing and managing mega-development projects with regional governments in Myanmar are a step in the right direction, it is not enough to ensure success. Hybrid systems that combine Union and Regional stakeholders are found to be more successful through case studies in SEZs and are certainly found to be more preferred, and these entities are also reflected in models of success across the region in Southeast Asia. Apart from SEZs however, this approach has not been fully attempted in other projects in Myanmar and urban megaprojects will tell whether this will indeed happen or not.

However, even though this approach is not yet fully attempted in Myanmar, we already see in the various case studies presented that this hybrid model is still limited in its success, and has yet another shortcoming. The final missing ingredient is the inclusion of external experts in industry related matters, who can lend both technical skills and measures of good governance to ensure the success of projects.

Though Myanmar has no experience yet in dealing with urban megaprojects, this will be a necessary hurdle to pass through in order to deliver on the many infrastructural needs of all sizes that are much needed in the country. Getting the right approach with integrated best practices would be key to set an example of good governance, that can be replicated across the country and boost further development.

Alex Aung Khant is Executive Director at Urbanize, a local policy institute for urban and regional planning. This post is part of a series of articles produced in the context of a fellowship program developed by the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) in partnership with Urbanize: Policy Institute for Urban and Regional Planning.

Like This Article