Yee Mon Hsu describes some of the findings in NEI’s new report on the decentralization of the MSME sector in Mon and Kayin states.

National Enlightenment Institute (NEI) is a non-profit political organization based in Mon State, with an accomplished history as a training centre and now also serving as a progressive public policy think tank. NEI has extensive programming experience, and expertise advising government departments, civil society and non-governmental organizations (CSO/NGO’s) at the regional and national level. NEI delivers high quality capacity building workshops, civic engagement trainings and related seminars for civil society organizations contributing to improved democratic practices, enhanced harmony and mutual tolerance.

Read the full report on the Konrad-Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) site here.

Political systems and economic systems influence each other. Political stability is essential for a nation’s economic development and in its absence, democratic development will be unstable and undoubtedly uneven. These axioms underpin why state building processes are central to both economic development and political stability.

For nearly five decades, Myanmar has endured a period of military rule. The military junta officially dissolved in 2011, followed by the installation of a nominally civilian government. In 2015, a general election was held and the National League for Democracy (NLD) won a supermajority of seats in the combined national parliament.

Despite the NLD’s electoral landslide, the 2008 military-drafted Constitution reserves significant levels of power within the government for the military, 25% with allotted seats in the legislature, a seat of vice presidency, and a few ministries under direct army control. This is why the Economist Intelligence unit, an authoritative voice on global business matters, refers to the country as having a “hybrid regime”. A political economy analysis of the country commissioned by the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) more bluntly refer to these constitutional limits of democracy autonomy, as a situation of ‘state capture’.

In Public Perceptions of a Divided Myanmar: Findings from the 2015 Myanmar Asian Barometer Survey, when the public where asked, ‘what is most important to pursue – democracy or the economy’ – most survey respondents opted for the economy. Taking this signal from the citizenry of Myanmar, this article focuses on the challenges inherent to state level decentralization as it related to government policies designed to help small and medium sized enterprises contribute to Myanmar’s economic development.

Decades of explicit military rule, followed by a continued, hybrid period of governance, has left Myanmar with a highly centralized political system. Civil servants of the Union government, State and Regional governments, and the Union Territories as well as State Owned Economic Enterprises are centrally controlled. Today, most decisions involving these institutional stakeholders are made in Nay Pyi Taw, the country’s official capital city.

The2018 political economy analysis of Myanmar commissioned by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs noted that shifting to a democratically-elected government, while allowing for a more inclusive policy-making environment, still struggles with an organizational culture of hierarchical decision-making embedded in Myanmar’s governance institutions. Additional challenges include tensions between some civil servants, due to military backgrounds and past loyalties, poor wage levels and outdated technology and systems.

Transitioning from the past and current challenges noted above is crucial for Myanmar’s future. Change must be inclusive, democratic and ultimately there must be a decentralization of decision-making in order to spur and maintain political stability.

The former ruling government of President U Thein Sein took steps to devolve some decision-making powers to the State and Regional governments and Township Authorities.

In 2015, at a workshop on Administrative Reforms, U Thein Sein called for “greater capacity building of the public service, decentralization, transparency and accountability.” At that time, Dr Zaw Oo, adviser to the president, said “the workshop discussions were designed to sharpen the potential of government staff.”

President U Thein Sen also instructed government institutions to coordinate with respective stakeholders in order to make flexible policies and regulations, because some laws take a great deal of time to amend.

The areas requiring far reaching reforms is extensive. The list includes modernizing infrastructure, addressing land rights issues, defining regulations for foreign investment, upgrading the country’s energy and telecommunications sectors, expanding both the scale and quality of education and healthcare services and so on. This immense set of needs, and the political reality of Myanmar governance system raises the question, where does one start?

The National Enlightenment Institute (NEI) with the support of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS) is making a contribution to this question by focusing its programming on strengthening the capacities of state institutions and civil society stakeholders, in order to promote MSME development.

Since 2012, NEI has worked closely with the government departments and the parliaments of Mon and Kayin States. NEI designed and delivered more than 175 public policy programs and workshops for nearly 14,000 citizens over the period of two government terms. NEI has made a name for itself as a “think tank and competency center” by providing advice and capacity building training to government departments, and civil society organizations operating in regional and national arenas. NEI’s programming strategically targets economic policy initiatives in order to improve Myanmar’s economic development.

Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME’s, often also referred to as SME’s) are particularly important in any economy, and crucial for growth and stability, particularly in developing economies. These are responsible for a significant share of job creation, poverty reduction, enabling cash flow at the community level, and they contribute to the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth of most modern economies.

The Asia Development Bank argues that SME’s are the backbone of the Asian economy, citing that SME’s make up 96% of all Asian businesses that provide two out of three private sector jobs in the continent.

According to Charltons Legal Consulting, (CLC) a corporate finance law firm with offices in Yangon, approximately 99.4% of all businesses in Myanmar can be classified as SMEs. CLC state that “on average, SME’s in Myanmar account for 50-90% of employment and contribute 30-53% of GDP in ASEAN member states”.

The Ministry of Industry is responsible for the development of the MSME sector in Myanmar, and established the Central Department of Small and Medium Enterprises Development. The department has 3 key functions: 1) Policy and international affairs. 2) Technology and market promotion, and 3) Investment and cooperation.

In 2016, NEI conducted a regional economic development needs assessment survey in southern Myanmar. This research revealed a strong desire for capacity building training to promote local MSME’s as an important economic development tool for the country. A series of five inter-related workshops were organized in cooperation with the Mon State MSME department and other related government departments, between 2017 and 2018.

The workshops were titled as follows.

1. Awareness-raising of social market economy system

2. Social enterprise and cluster development of integrated approaches in regional economic development

3. Fundraising opportunities for SME development with banks, microfinance and venture investors:

4. A dialogue to raise awareness of revenue models and fair taxation systems

5. Salt industry: Cooperative markets strategy workshop

Decentralization process and delegation of decision-making and implementation of economic development policies to regional levels have been underway for some time in the country. For example, the central government delegated governance of bank loan procedures to regional governments. However, it has not gone well.

The Milken Institute, and reports from the German Development Agency (GIZ) amongst other financial sector analysts, point to three reasons why such challenges occur. (1) The public has a significant degree of distrust in banks, (2) there is a lack of credit assessment capabilities due to the shortage of bank personnel, and (3) companies seeking loans are reluctant to supply information needed for credit assessments. It is no surprise that in the case of SME’s, the vast majority of these business owners are often unfamiliar with such procedures and will not likely have a strong credit history or collateral for traditional banking institutions.

What may seem to be a simple measure, i.e. devolving the governance of banks loans processes, can have complex implications. A Roland Berger study of the country’s banking system revealed that in 2016, Myanmar’s banks’ assets-to-GDP ratio (49%) were the lowest amongst its ASEAN peers. This stood as a clear indicator of Myanmar’s under-developed banking sector. Despite starting from a low point, the Berger study also showed that Myanmar did experience the fastest rate of asset growth rate (18%) between 2012-2015.

While these comparative figures might be seen as optimistic, prudence is warranted.

The recent and controversial resignation of the Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Myanmar (CBM), U Soe Thein, stands as a case in point. In an exchange reported in Myanmar Times on the issue of non paid loans (NPLs) from businesses, U Soe Thein noted there was a large amount of unpaid business loans (which may have accounted for the high rate of asset growth) and that banks needed to be stricter when issuing new loans and they had to be more diligent in their efforts to collect debt from errant borrowers.

The Central Bank of Myanmar disagreed with their own Deputy Governor’s characterization of the situation and his proposed remedies regarding NPLs. At the time of this writing, the CBM has not accepted U Soe Thein’s resignation.

Clearly, as can be seen in this case, devolution has not been a straightforward path.

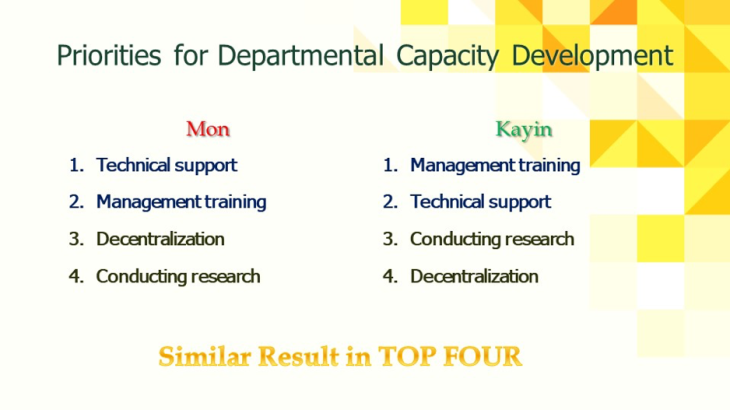

NEI has experience in assisting Mon and Kayin States in developing their respective MSME action plans. In 2018, NEI agreed to evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of government departments tasked with managing the MSME file. A study was designed to look at how decentralization of the MSME sector has unfolded in Mon and Karen States.

The study considers a number of interrelated processes impacting decentralization. This includes, democratization, institutional frameworks and reforms, economic liberalization, and national integration processes.

MSME’s are dependent on the private sector for access to capital and must comply with the state and national level regulatory environments established by the executive and legislative branches of the Union government as defined in the 2008 Constitution. Our survey targeted respondents from these groups in Mon and Kayin States.

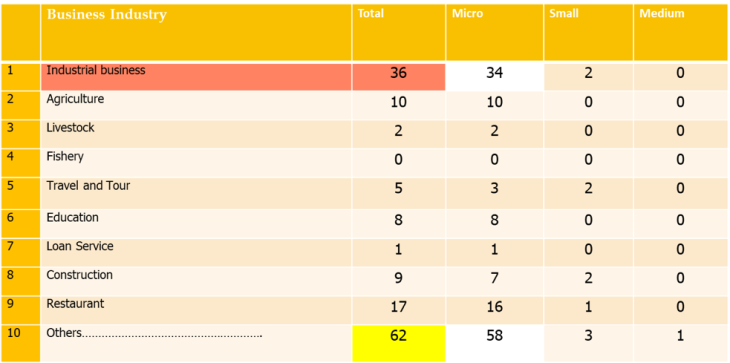

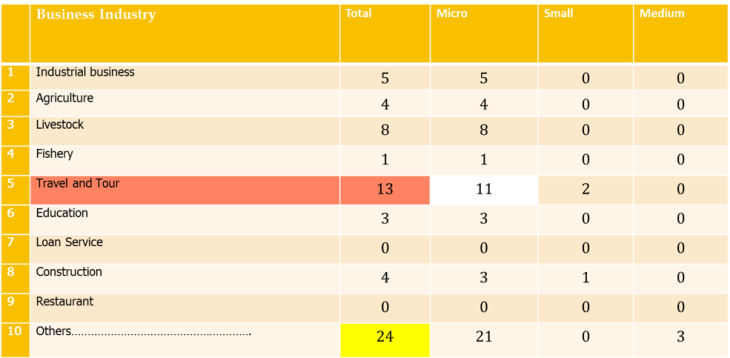

At the time of the survey, there were 1010 registered SME members in Mon and 182 registered in Kayin. We surveyed a total of 199 respondents who had registered their SME operations with either the Mon or Kayin government departments — 150 were from Mon’s 10 townships and 49 were from two townships in Kayin. Respondents had businesses in the sectors that included; industrial, agriculture, livestock, fisheries, travel and tourism, education, financial loans, construction, and restaurants. (Refer to Picture 1 and 2)

We also conducted in-depth interviews with high-level respondents (Assistant Director to Deputy Director personnel) from the Union and State levels of government (Mon and Karen) who have economic sector planning responsibilities.

These key informants were asked;

1. What are the obstacles to operate a business at the regional level within a centralized administrative system?

2. What were their opinions on decentralization and what do they believe are the priorities?

3. What was their assessment of the governments capacities, the challenges, opportunities and how and when to make improvements?

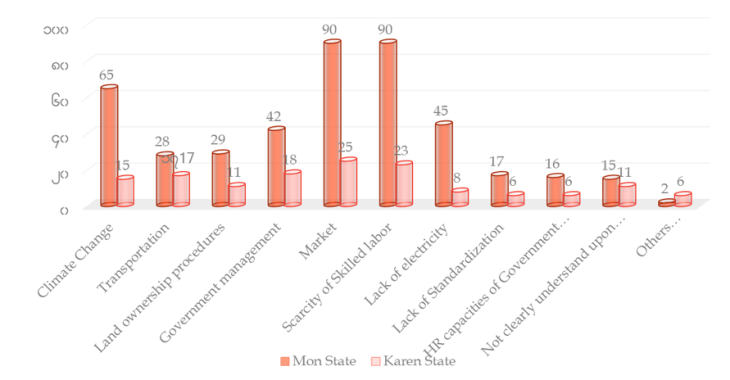

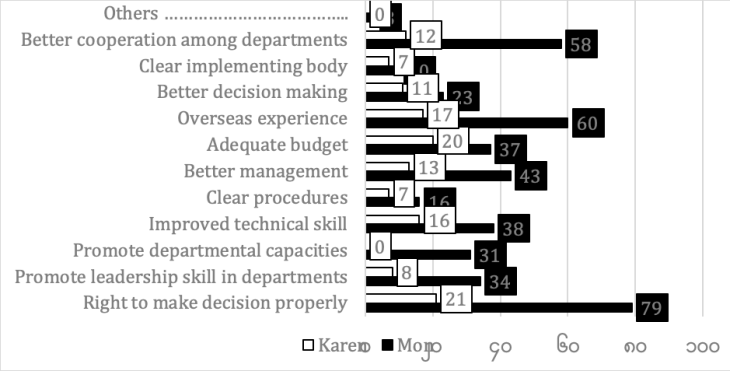

Respondents from Mon and Kayin states prioritized that improving their market access was the top challenges facing the SME sector. Scarcity of skilled labour also ranked highly amongst respondents from both States. The challenge of government management ranked higher in Kayin while the lack of electricity and climate change impacts were seen as top tier priorities for respondents from Mon. (Image 3)

Although both States were badly affected by flooding in recent years, the business losses have been greater in Mon State. We also noted there are more mechanized factories and businesses that rely on consistent access to electrical power. This helps to understand why Mon State respondents prioritized the need for more reliable electricity access and government measures to mitigate losses linked to extreme weather events like flooding.

Kayin respondents prioritizing government management of their SME sector is better understood given the region’s reliance on tourism and cross-border trade concerns. The reality of on-going ethnic armed conflicts in Kayin also negatively affect tourism and macro-level cross-border customs, tariffs and trade issues with Thailand impact SMEs linked to the movement of goods and services across the border.

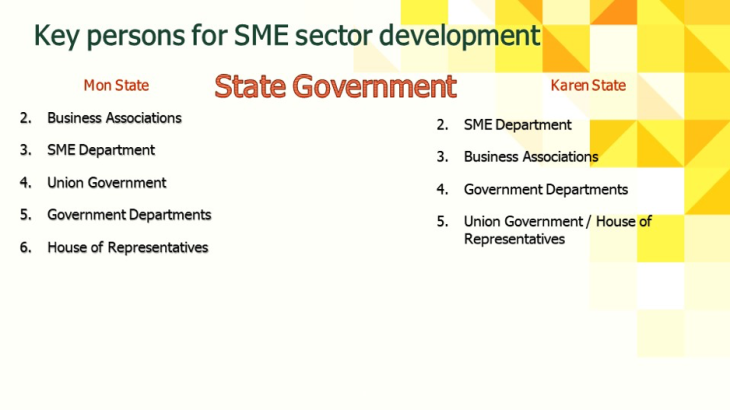

Our survey research found the economic strengths of each State influence how respondents view decentralization. Mon State’s economic strength lies in providing supply chains and mechanization-based industries. SMEs linked to this form of economic activity require reliable access to electricity and good transportation infrastructure. Meanwhile, Kayin State benefits from cross-border trade, tourism and SMEs that are tied to the services sector. We can hypothesize the implementation of decentralization initiatives will likely have better results by taking into account the comparative economic advantages of different regions of the country. (Refer to Images 4 and 5)

56% of respondents affirmed the general need for better administrative integration and coordination between the macro-level of government institutions like the Ministry of Planning with State and Regional levels of government when designing the decentralization initiatives.

Similarly, 56% of respondents believe their SME civil servant staff groups are adequately skilled to perform their tasks.

The survey also found that decentralization is happening faster than people expected, and with impacts that were unforeseen as indicated in the earlier description of devolving the governance of bank loans to state level authorities. Different states are also experiencing decentralization in different ways based on their unique geography, ethnography and economic strengths.

Finally, there is a number of larger structural challenges that need to be addressed such as; the lack of clarity on rules and regulations pertaining to SMEs; lack of staff and elected MP understanding of SME’s realities and poor responsive capacities; poor communications between Ministries; confusion between different ministries regarding their respective SME mandates and obligations; NPT level structures do not correspond with State level structures and SME operators not being clear which government agency to contact for assistance. (Refer to Images 6 and 7)

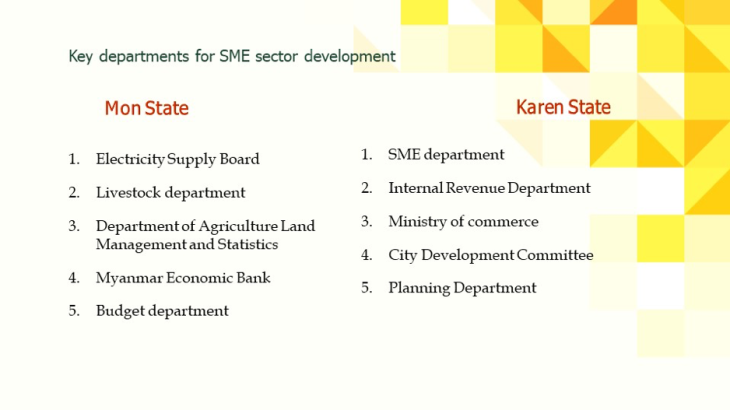

Our survey showed that for the benefit of the industrial sectors in Mon State, specific government departments including, the Electrical Power Department, Livestock and Fishery Department, Department of Agricultural Land Management and Statistics, Ministry of Planning, Myanmar Economic Bank and Budget Department are all critical to involve collaboratively in the decentralization process.

For Kayin State their SME agencies, Customs Department, Ministry of commerce, Municipal Committee, Ministry of Planning are important role to involve because of the prominent role the tourism sector plays in economic development.

Our survey research proposed the following recommendations to respond to these challenges.

Finally, a government-wide organizational culture change is needed that leaves the legacy of hierarchical decision-making behind. In its wake, stakeholders need to embrace a more shared and devolved responsibility of advancing Myanmar’s economic sector by supporting the diversity of SME operations across the country.

Yee Mon Hsu is Executive Director and co-founder of National Enlightenment Institute (NEI) which is based in Mawlamyine, Mon State, Southern Part of Myanmar. After graduating with an Honours Degree in Computer Technology Mawlamyine Computer University in Myanmar, she continued her studies in Tourism Management at Singapore. Currently, she is also involved in the Regional Tourism Development Committee of Mon State as a Tourism Expert in that committee. She is also a member of Advancing Leaders for Myanmar Prosperity Program of Deboer Fellowship, Young Political Leaders in Asia Program of Konrad Adenauer Fellowship, Rural E-commerce development program (Mekong Institute- Mekong Lancang Countries Program). She also works as a consultant, expert for local businesses, tourism and regional economic policy issues in order to promote Mon State development.

Like This Article