Duncan Burry notes the promise ride-hailing apps hold for Myanmar’s future.

Hello Cabs, Myanmar’s first ride-hailing app, was launched in Yangon in August of 2015. Oway Ride, a local rival, was not far behind, launching in February 2016. And then two large international players were launched in 2017: Grab in March and Uber in May. Ride-hailing is clearly a competitive space.

The presence of these apps in Yangon is striking because the market is inhospitable for disruptors. Ride-hailing platforms usually undercut an oligopolistic taxi marketplace, where fares are high and supply is tightly controlled. Yangon, by contrast, is a low-margin market with cheap fares, abundant supply and no established taxi association.

Yet, these apps face two immediate difficulties.

The first is fragmentation— four is too many ride-hailing services. Anirban Chakraborti, Hello Cabs’ CEO, points out that excessive fragmentation in a market never helps. “You only ever need two, or maximum three dominant players in the market,” he says, concluding that not all will survive unless there is merger or acquisition activity between the companies.

As for the second, ride-hailing platforms will have difficulty undercutting, or even matching, the speed and cost of hailing a cab from the street. However, the apps do have an advantage in remote pick-up spots, where taxis are scarce.

Despite these obstacles, the ride-hailing platforms are finding ways to add-value that could help reform the market.

Currently, there are too many taxis on Yangon’s clogged streets— around 70,000 taxis for a city of approximately 5 million people. This is twice the number of Singapore, a city of a similar population. Ride-hailing platforms can generate valuable data and improve market efficiency through better allocation. This could cut Yangon’s taxi numbers down.

Talk of reducing numbers in Yangon raises valid concerns about driver livelihoods. Addressing this requires an active approach to regulation. A labour-market programme to re-skill drivers is likely to be too costly. Another option is to create policy that encourages drivers and taxi owners to migrate to underdeveloped taxi markets. The ride-hailing platforms could help facilitate this.

Mr Chakraborti points out that Mandalay, which lacks competition among taxis, could be a valuable market for the bigger platforms. “There you might need bigger companies to put their money in to lower the cost,” he says, “there might be some fat in that market.”

Oway is now actively pursuing Mandalay, where it has a team in place. “We already have at least 200 [motor]bikes and 300 cars and that’s going to be a big market for us,” says Nay Aung, Oway’s CEO.

Redistributing drivers and taxis would not solve another fundamental problem: many of Yangon’s older taxis are in a sorry state. This means frequent breakdowns and ongoing maintenance issues. Crucially, many are unsafe. An important way ride-hailing apps can add value is by instilling higher safety standards.

For Oway, Mr Aung explains that there is a mandatory process for checking and verifying each vehicle it accepts to the platform, which must pass a test to ensure proper functioning.

For its part, Uber is taking a very active approach to ensuring safety standards. They only accept registered, and therefore insured, taxis that are less than 15 years old. Sam Bool, Uber’s expansion general manager for Southeast Asia, describes a process by which vehicles are taken to a workshop and given a full-body mechanical inspection, including looking under the car at the brakes, suspension and tires. “We’ll be setting up quite a large workshop scalable enough to handle the throughput that we’ll be putting through,” says Mr Bool.

He also points to technology built into most phones that can improve safety. In other markets, Uber already uses information transmitted from phones to determine whether they are in a dashboard-holder or the driver’s hand. “Things like this are really the next frontier,” says Mr Bool, “based on the telematics, we can also see whether a driver is accelerating too quickly or braking late or too sharply.”

These encouraging efforts must be coupled with effective policy to replace decrepit taxis, which would bring advantages beyond improved safety. “If the government can come up with a plan where they allow for import or some partial import with a duty-free structure for [taxi] vehicles which are new, there would be a lot of savings on the maintenance and the fuel costs,” points out Mr Chakraborti.

Lastly, in terms of safety, effective driver training is also adding value. When recruiting taxi drivers, Oway provides specialised training. In addition to service, the training covers safe driving, accidents and maintaining a car. Mr Aung concedes that it is difficult to determine the resources to allocate to training drivers. “We bring them into a classroom, we give them our material, we train them and we assume that this is going to be exclusive, but they’re not, right?”, he says.

Some of the platforms are also offering cash-free payment methods as a streamlined alternative. While promising, it may be difficult to encourage e-payment take-up in this cash-based economy.

Grab has partnered with Wave Money to integrate its own e-money platform, GrabPay. Passengers can load cash onto an e-wallet, and drivers can cash out e-money at Wave Money outlets at the end of each day. Oway is moving towards a similar system it calls Oway Pay.

These platforms can improve efficiency further with sophisticated uses of technology, and not just when it comes to payment. Mr Bool describes forthcoming features in Uber’s platform whereby a driver dropping someone off is sent trips at, or near, the drop-off point, and drivers are forwarded trips that are on the way to a later-scheduled pick-up.

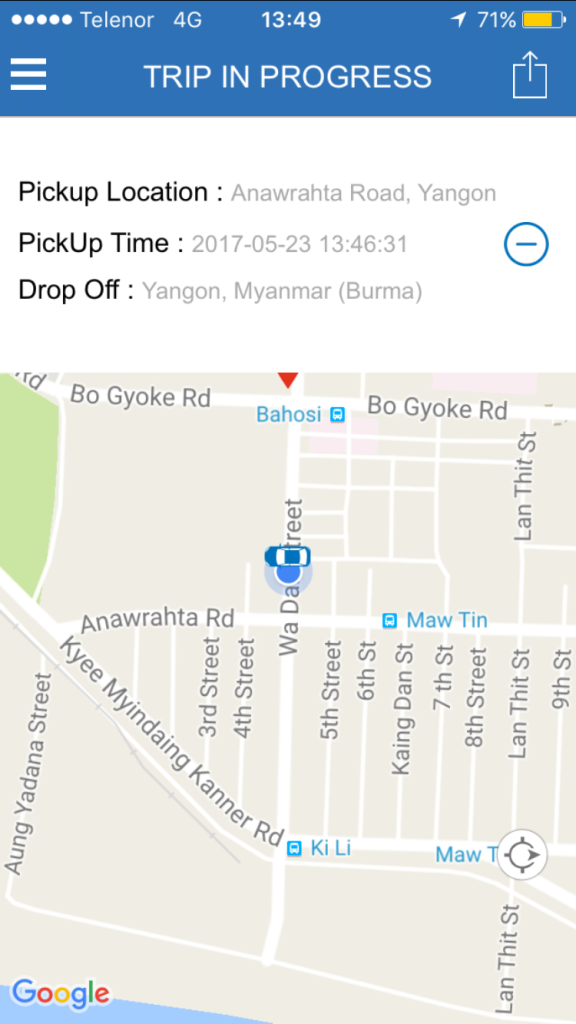

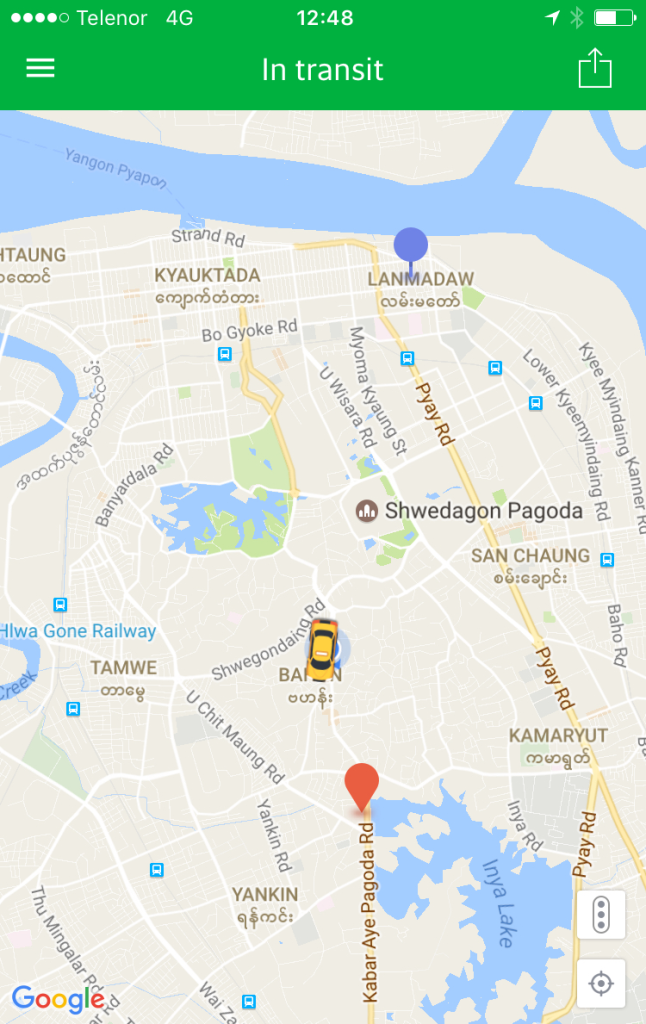

A lingering technological problem is imprecise online maps of Yangon, on which the platforms are dependent: “That is something [Oway] is seriously looking at, improving the map capability on top of the Google map,” says Mr Aung.

Mr Bool identifies mapping as one of Uber’s biggest early challenges. Ei Phyu Lwin, Uber’s recently appointed General Manager of local operations, says finding solutions to such challenges requires “partnering with local businesses here who know the market, who have faced these challenges and dealt with them successfully.”

Ride-hailing apps could bring about vital improvements to safety, service and traffic management. If the model finds its footing in Yangon’s peculiar market, the advances could be expanded to Myanmar’s other cities, which currently lack taxis.

Oway is already leading the charge in Mandalay, where the motorcycle market offers a cost-effective alternative to cars— an option unavailable in Yangon, where motorcycles are banned. Naypyidaw’s population could make it an attractive next step. The ideal, however, is more far-reaching: nationwide ride-hailing that provides orderly, safe and predictable transport options— services available at the touch of a button. Each passenger could expect the timely arrival of a vetted, trained driver with a proper taxi license, and a vehicle that is in good condition, ensuring safety for both parties.

While the path to success is not assured, the arrival of the ride-hailing platforms is cause for optimism. Here’s to a future that does not involve getting drenched trying to find a cab during the monsoon season.

Duncan Burry is a graduate from Melbourne Law School. The above article is part of a research project on ride-hailing platforms in Myanmar that Duncan was involved in during his time at Consult-Myanmar Co Ltd in Yangon.

Like This Article

November 22, 2023

July 13, 2022

January 26, 2022

October 14, 2021

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023