Klara Christensen explores the music scene in Myanmar.

Walking the parks of Yangon last year in May, I could not help but notice the groups of young men – and sometimes women – sitting on the grass in longyis singing their hearts out in the hot night. Often the melody was well-known to my Western ears, but with Burmese lyrics and accompanied by a guitar of modest quality changing hands between the youngsters. I was told that this phenomenon is quite new, as youth gatherings like this were not approved by local authorities half a decade ago.

I experienced Burmese culture through a lens of music, and to me it resembled some of the contested discourses and changing dynamics of a country in transition. In tea shops and buses, on TV and radio, I always heard hits from Europe and the US transformed into the so-called “copy songs” with lyrics on love or praising a new achievement of the government. From my talks with local musicians such as Lone Lone from MJN, Darko C from Side Effect and Eugene from Skunx, I learned that the mainstream music scene is not built by individual bands, but rather by professional individual musicians and singers collaborating in various constellations, often playing songs written by a professional song-writer. The songs are distributed via radio broadcasted from the government capital Naypyitaw.

The mainstream music scene is thus on the one hand very traditional and shaped to suit the conservative elite, while on the other, trying to resemble Western music as closely as possible. There is thus very little traditional music, perhaps because of its ethnic connotations. And despite the removal of censorship several years back, there is a surprising lack of experimentation with lyrics and style. To me, it seemed that this could either be a sign that censorship was de facto still in place, or that the music culture had been so tamed after 60 years of repression that it was difficult for musicians to find their own voices.

While I mostly acquainted myself with mainstream music in public transport, I had much more personal contact with the underground scene in Yangon through my work with Turning Tables Myanmar, an NGO that works to empower marginalized youth through music and video production. These musicians were self-taught and often equipped with a political, rebellious text universe and a distaste for mainstream musicians. While these artists took pride in writing their own music, it was still heavily inspired by Western bands, and at our festival last year all 30 bands had English names such as Side Effect, Suicide Plan, G-Tone and Bliss. It was puzzling to me how both the mainstream pop-culture and progressive music scene were looking towards the Western music scene, albeit from different perspectives. Only a few musicians try to work with the traditional music of Myanmar by sampling beats and riffs into electronic tracks in the up-and-coming dub-step scene.

The underground scene is an urban phenomenon. While there might be around 60 bands in Yangon, the numbers fall to a handful in Meikhtila and Mandalay, and when we travelled to rural areas of the country (Pathein, Loikaw, Myitkyina), there was mostly Church-based music with light lyrics and soft vocals. My fellow musicians from Turning Tables found themselves far from home, and the clash of music cultures revealed the very different paces of progress between Yangon and the rural Myanmar. Walking down the dirt roads of a tiny mountain village, our black denim and sunglasses reflected a very different world and worldview than what was the lived experience among these villagers.

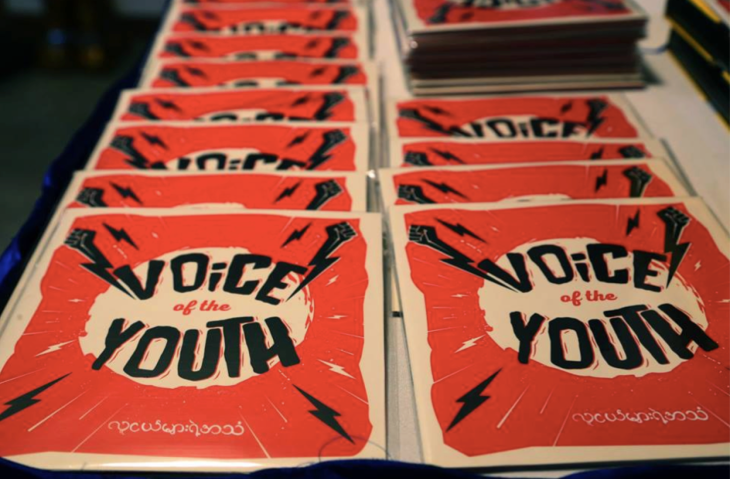

When I first arrived in Myanmar, I was very excited to organize a music festival, but I was not aware how controversial it was to do so. In 2015 we were able to produce(?) the first youth music festival with underground bands from all the bigger cities, with some of the concerts even being broadcasted on national TV. However, we still had to have the festival on diplomatic grounds at the French Institute, and my manager Darko had to sign a waiver with SkyNet to take personal responsibility for any inappropriate happenings. When a dozen students got arrested in the spring of 2015, we halted our dissemination of festival flyers, as we were concerned that our leaflets with “Voice of the Youth” printed on them could lead to trouble. Moreover, when we produced an album based on the festival, several songs were rejected by the authorities and could not get on the album in their original format. There was room for change, but it was definitely restricted and none of us really knew where the line was drawn.

“After one time they say no, once they’ve seen the band, they think it’s noisy and they don’t get much money. Even though it’s a peaceful concert they’re afraid something will happen.”

Moreover, the process of obtaining a government permission can be long and complicated, sometimes requiring the band to play at specific venues that are out of the price range of both audience and musicians.

As many cannot afford the government permission, underground concerts are often held illegally, a fact that hinders any public advertisement and makes the concerts subject to being closed down.

The economic, administrative and logistical challenges mean that many of the underground bands have never performed live, and the most established underground bands can only set up 2-4 concerts a year, reaching a quite limited audience. In general, as there is no platform for the underground scene, young progressive musicians find it difficult to meet and play, leading to a feeling of isolation and hopelessness. This is especially true for groups facing discrimination in the general society such as religious minorities and women, who are almost absent in the music community.[5] Also, youth from outside of Yangon have severe difficulties forming bands, finding practice space and being allowed to perform publicly. The few music venues allowing progressive bands are often flooded by expats and do not provide the much-needed safe space for Burmese artists’ self-expression.

To me, this experience with the music scene in Myanmar illustrates the ambiguity of the progress we witness. While change is happening, it is in different tempi and by no means straight forward. It is divided between rural and urban, male and female, young and old. There are clear ethnic differences, and non-mainstream artists face heavy discrimination from local authorities and music venues owned by cronies. However, the fact that last year’s Voice of the Youth Festival is going strong again this December could be a sign that room is being made for dissident voices to be heard (for videos and updates, check https://www.facebook.com/turningtablesmyanmar/?fref=ts).

Big thanks to Darko C, I2, Eugene, Skum and LoneLone for sharing their thoughts and experiences.

While currently pursuing a master’s degree in Social Policy at Oxford University, I have previously worked for Turning Tables in Myanmar coordinating a music dialogue project for marginalized youth. My current interests revolve around conflict mediation between ethnic groups in post-conflict settings and how music can e an integral part of trust-building.

Like This Article

November 22, 2023

July 13, 2022

January 26, 2022

October 14, 2021

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023