Alex Aung Khant reflects on the recurring nature of the urban problems he encounters daily.

Since my last essay on Yangon’s urban challenges, I came across the scenes, pictured below, by coincidence on my daily commutes around town. Most of these scenes are situated in downtown Yangon, the older, southern half of the city that was planned and built during the colonial period. In Southeast Asia, few cities that have managed to keep their colonial heritage intact. Yangon, in particular, has been well-known for its surviving heritage buildings and wonderful architecture, but fewer people know that our surviving heritage is more than just on the surface, but descends much further into public infrastructure.

The majority of the sewage drains, pipes and supporting systems that service downtown Yangon also date back to the time of the British. The huge boom in development over recent years has severely stressed this vital public infrastructure. If roads are the arteries that supply and nourish a city with people and resources, then drains are its veins.

Fortunately, the current Yangon regional government, under Chief Minister Phyo Min Thein, has quickly realised the urgent need to bring about a swift and effective overhaul of this rusting system. However, the way in which these public projects have been carried out by the municipal body— the Yangon City Development Committee (YCDC)— provides reason for concern.

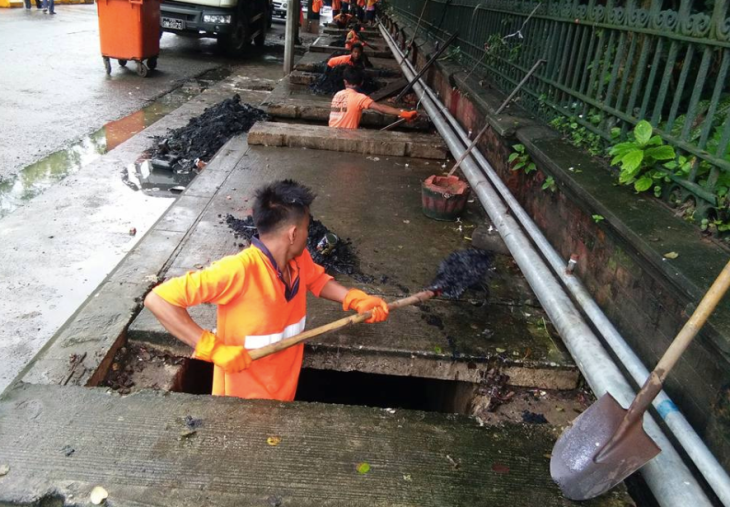

With the end of every monsoon season, the YCDC embarks on a grand annual mission of repairs to keep its tattered mechanisms running. Within the YCDC— infamous for corruption at all many levels— it is common for public projects to use cheaper, lower quality materials and then produce fraudulent balance sheets, listing prices for products of better quality than those used. Lackluster supervision and management, in addition to the use of untrained manual labourers as its primary workforce, also contributes to improper technical implementation of the majority of their projects. Due to budget constraints and a long list of other shortcomings, only patchwork maintenance and repairs can be made to certain pockets of priority areas. Scores of labourers from the suburbs of Yangon are hired every year for a meagre wage, toiling under the sun and rains to unblock drains and repair damaged roads.

After all that trouble and toil, what is most surprising is that very little of these efforts actually contribute to preventing the next monsoon from wrecking the same havoc on the flimsy state of Yangon’s roads and drains. Instead, with the next monsoon, this cycle repeats again as residents are forced to watch a rerun of the same dreadful episode. This cycle of samsara has gone on for as long as I can remember, and the horrible conditions these workers are made to work in produces an environment that most city residents would never be willing to be around, let alone work in. All aspects of health and safety, and precautions against work hazards, have clearly been thrown out the window. So far, there are no prominent labor unions or health organizations working on this issue.

It is disappointingly clear that there need to be drastic changes through which Yangon’s municipal body will fix itself, in order to fix the city. The use of proper machinery and equipment, rather than relying on manual labor, a commitment to correct technical applications, and a guarantee of long-term reliability of their infrastructure, as opposed to the pursuit of cheap fixes— these are just a few of the necessary steps that should be incorporated into the YCDC’s day-to-day practices on all public projects. Otherwise, all efforts will merely be cosmetic cover-ups atop core problems. It will only be a waste of time, energy and resources if the city is to remain stuck in this metaphorical swamp of repairing broken roads and blocked drains.

If the city is to catch up with other global metropolises around the word, the YCDC should also be taking pre-emptive measures in anticipation of the projected growth of the city, and the inevitable challenges ahead. As one example, along all my walks and commutes around town, I’ve seen very few trash bins— a key preventive strategy that encourages proper garbage disposal. Nobody wants to get their hands dirty, but frankly, it is also hugely disrespectful to these workers, knowing full well that next year, they will be back again in chest-high sewage water. Even the media has shown little interest in following these tragic stories of reckless public expenditure. With little public concern for these projects and their effectiveness, the working lives of these laborers are of grave concern as well.

Sometimes, there is no simple way to shovel our way out of this city’s problems.

Alex Aung Khant is Executive Director at Urbanize, a local policy institute for urban and regional planning. Alex is from Yangon, Myanmar, and holds a Masters degree in Urban Studies and Public Policy from Sciences Po in Paris, France. He obtained his B.A. in Political Science and Asian Studies, also from Sciences Po Paris.

Like This Article

November 22, 2023

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023