Marie Puyessegur explores events in part one of a three-part series conducted as part of the MEMORY! Heritage Film Festival, an annual event in Yangon.

The festival’s 2018 edition focused on the theme of Freedom of the Press and Democracy in their representation through cinema, and was supported by a grant from the Global Research Network on Parliaments and People. The research detailed here was conducted over the course of ten days from November 7-16, 2018, by a team of three researchers, and hopes to shed light on the current attitudes and debates that surround the question of freedom of expression during the country’s transition.

The three articles in this series will individually examine three of the festival’s programmes, which took place simultaneously in Yangon and provided different approaches to the themes of artistic and journalistic freedom in Myanmar: the Journalism and Culture workshop, a journalistic workshop organized in conjunction with the Myanmar Journalism Institute; the Myanmar Script Fund competition targeting young filmmakers; and a conference gathering various international experts around the topic of Press and Democracy in Myanmar and the Asian continent. In forthcoming contributions, Kimberley Pallenschat will examine the themes and challenges faced by Myanmar’s emerging generation of independent filmmakers, and Theo Stojanov will discuss the proceedings of the Press and Democracy conference.

“Is anybody still struggling with their angle?” On Sunday 11th November, the room next to the projection booth at the Waziya Theater was buzzing with questions. With the help of an interpreter, twenty-four young journalism students and their instructors went over the problems that they had encountered in their coverage of the 2018 edition of MEMORY!, a film festival annually held in Myanmar’s former capital city: an interview that fell through, an unsatisfying angle, an issue with a deadline. Throughout the day, the students dispersed around the room, alone or in pairs, working on their stories on the workshop’s computers and occasionally checking Facebook on their phones. As the daily discussion ended, French reporter Carol Isoux reminded the students that the deadline for filing their stories for the workshop’s print publication, Bioscope News, was only a couple of days away, and the class dispersed.

From November 5 to 16, 2018 the Waziya Theater, Yangon’s oldest colonial-era cinema, was home to the Myanmar Journalism and Culture initiative (MJC), a joint program now in its second edition, organized as a partnership between MEMORY!, a French organisation headed by Séverine Wemaere and Gilles Duval, and the Myanmar Journalism Institute. Established in Yangon since 2014, MEMORY! International Heritage Film Festival aims to bring to local audiences the international and regional cinema to which the country, despite its rich cinematic history, has had little to no access in recent decades. As well as providing support to emerging local filmmakers through a yearly script competition, the festival’s emphasis also lies in the preservation of Myanmar’s film heritage. The Myanmar Journalism Institute (MJI), founded in 2014, is one of the country’s two independent journalism schools. The MJI trains students in print, online, video, and photo journalism, and most of its graduates go on to work for public and privately-owned media, after a one-year training period that renders them in high demand in a country where journalists often lack formal training. This year’s graduating class, which makes up the workshop’s twenty-four students, is comprised of fourteen women and ten men, ranging from age 17 to 33. As a reflection of the MJI’s efforts towards gender and ethnic inclusion, they come from all over the country, despite Yangon’s expected overrepresentation (only fourteen of the participants originated from the country’s main ethnic group, the Bamar). By encouraging a critical and analytical approach to cinema and the arts that goes beyond entertainment journalism to interrogate the intersections of the arts, politics and society, the MJC hopes to foster a culture of independent reporting, and to mobilize critical engagement with politicians and cultural policies amongst Myanmar’s future reporters.

Supervised by French reporters Carol Isoux and Jêrome Boruszewski, local trainers Su Myat Wai and Ko Zayar Min, and Chris Peken, who works with the MJI as a consultant and capacity-builder, the participants spent ten days covering the screenings, events, and themes of the festival. They were able to interview organisers, local and foreign filmmakers, scriptwriters and producers, as well as some government officials. The workshop gave students the opportunity, early on in their curriculum, to immerse themselves in an intensive period of writing and reporting. Individual blog posts are published on a dedicated Facebook page and twelve articles, written in pairs, in an ad hoc publication called Bioscope News – 3,000 copies of which were printed on the final day, assembled by the students, and handed out for free to passers-by and festival-goers. MEMORY!’s 2018 edition was, following the previous year’s focus on Banned Films and Censorship, centered around the theme of Press and Democracy, and on the depiction of reporters on screen – at the confluence of two media (journalism and cinema) whose uneasy and incomplete emergence from a strict regime of state-sanctioned censorship have dominated the recent national and international conversation.

Cinema has a long and rich history in Myanmar, dating back to the 1920s. The years of internal struggle following the country’s independence in 1948 have, however, greatly harmed Myanmar’s cinematic heritage, which has now all but vanished. Audiences have just recently gained access to the foreign films that had practically disappeared from screens during several decades, as Ne Win’s coup in 1962 reduced a vibrant local film industry to a state-sanctioned bureaucracy. MEMORY! thus finds itself in the somewhat paradoxical position of screening extremely well-known, often Western, film classics to an audience that previously had very little access to worldwide film heritage. Film production remains, to this day, subjected to a strict regime of control and censorship. A promised update to the Film Law inherited from the military-era regime has remained in administrative limbo for two years, and the Film Classification Board under the Ministry of Information was re-established in 2014 after a brief period of abolition. As a result, the Myanmar film industry is still subject to a regime of censorship that prohibits critical depictions of military conflict, of poverty and religious or sexual themes – or even unhealthy behaviours: as the festival was taking place, the streets of Yangon were covered in posters promoting director Na Gyi’s lavish melodrama Mi, the heroine’s cigarette obscured by a tiny “no smoking” sign.

For our small team of three researchers, the festival, with its multiplicities of events, of local and international, official and independent actors, and occasionally competing interests, provided a window into the dynamics, obstacles and tensions that accompany Myanmar’s transition towards a more politically, socially, and economically open society under a watchful international eye. Yet freedom is elusive. Taking place six years after the abolition of media censorship, four years after 2014’s News Media Law that guarantees journalists “freedom from censorship to express, publish or distribute freely”, and amidst the recent turmoil surrounding the press coverage of the Rohingya crisis, the workshop provided precious insight into a continuous process of transition. It shed light on the diverging ways in which local and foreign actors navigate current uncertainties over the role and responsibility of the media, questions of freedom of expression and self-censorship, or the presence of international interests within Myanmar’s shifting political conditions.

As Chris Peken, an Australian journalist who works for the MJI as a consultant, explained:

...“in Europe or in Australia a journalist knows where the line is. The line is very clear, it’s delineated. It is pretty easy to understand as a journalist when you’re getting close to or risk getting over the line. […] The problem in Myanmar is that the line is more like a wave, or it fades in and out of focus. Journalists don’t know where it is. […] And if you’re unsure where the line is, you’re going to step a couple of extra steps back, to be sure that you don’t get too close because you can’t see it. Your self-censorship as a result is going to be far heavier.

The MJC workshop took place only a few weeks after the sentencing of Reuters reporters Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo to seven years in prison for breaching the Official Secrets Act during their investigation of the Rohingya crisis. The students, however, appeared undaunted by such a tense climate, and were seemingly free from any inclination towards self-censorship – a boldness that the instructors attributed to the participants’ lack of exposure to the complex balance of Myanmar’s media sector (even though some already had, as is not uncommon, previously worked in the media for a couple of years as teenagers). Only one student admitted to being apprehensive during class discussions, while a couple of the others even professed that they were willing to face prison time. Altogether, trainers noted the participants’ motivation, their occasional “feistiness” during interviews with un-forthcoming officials, and their enthusiasm in selecting and discussing articles that touched upon topics as sensitive as film and media censorship, or the accountability of the press. One of the local instructors relayed that journalists were currently facing significant opposition and criticism within civil society – highlighting the students’ sense of a calling in pursuing a path that, to many, at present appears to be unappealing.

In that context, the equilibrium between the often inexperienced students, and the instructors who acted as their editors was quite delicate. While MJC participants had free rein in choosing the angles of their articles, which were to be distributed through print and online publications that they had full control over, there were instances during which the local trainers stepped in, to maintain the delicate balance of Myanmar’s media ecosystem – the ramifications of which the students may not yet be aware. “A Press Not Yet Free,” authored by students Kyaw Swar Htun and Gayhtaw and outlining the legislative barriers against freedom of expression, generated debate by featuring a quote from reporter Zayar Hlaing, regarding Myanmar dropping from 131th to 137th place in Reporters Without Border’s 2018 World Press Freedom Index: “The government should feel ashamed of that situation. Those indexes highlight that our democracy is not in good shape.” The quote, despite the concerns raised by the instructors during the workshop, remained in the final article – highlighting the latitude of print journalism relative to Myanmar’s film industry, where any negative mention of the government, as per our interviews with Yangon Film School students, ends up on the cutting room floor. A photo depicting the poster of The Maw Naing’s banned film The Monk (2014), however, was edited out of the publication’s layout – despite quotes from Aung Min, the film’s scriptwriter, being featured in the text, and on the review’s cover, arms raised under the bold headline “Waiting to be set free.” As evidenced by such discussions, the constant reassessment of risk and protection is at the heart the informal mechanisms of self-censorship that still prevail within Myanmar’s ambiguous legislative framework, of which the workshop, despite its intentions and the exceptional circumstances created by its foreign-backed context, might have unwittingly given students a first taste.

Overall, the final articles demonstrate the young reporters’ willingness to tackle topics they knew to be sensitive. Freedom of the press was the overarching theme of this year’s edition of MEMORY!. Gilles Duval and Séverine Waemere’s programming, however, claims political neutrality by focusing on the depiction of journalists in cinema: films like All the President’s Men (1976) and Godard’s How Is It Going (1978) (which explicitly interrogate the transgressions and responsibilities of the media) were screened alongside more neutral entries such as René Clair’s It Happened Tomorrow (1944), Antonioni’s The Passenger (1975) or Kurosawa’s Scandal (1950). Social or aesthetic questions, however, were often bypassed by the participants of the workshop in favour of political angles. The barriers to freedom of expression in Myanmar were the overarching theme of Bioscope News, the workshop’s publication: articles by Aung Khant and Su Myat May Zaw ( “Waiting To Be Set Free”), Han Toe San and Su Su Mar (“Myanmar Journalism Strives for the Silver Screen”), Ko Thu and Luck Yadanar Bo (“Myanmar Films Shown On The International Stage, But Are Banned At Home”) thus explored the censorship of cinema and the obstacles faced by recent films such as The Maw Naing’s banned The Monk (2014) and Wine’s Letter to the President (2018), the rare Myanmar film to feature a journalist and a lawyer as characters. The aforementioned “A Press Not Yet Free” article, written by Kyaw Swar Htun and Gayhtaw, laid out the legislative obstacles to free expression in Myanmar media and, using a number of provocative quotes from professional reporters, explicitly called for their removal, and for the withdrawal of all current charges against press and media personnel.

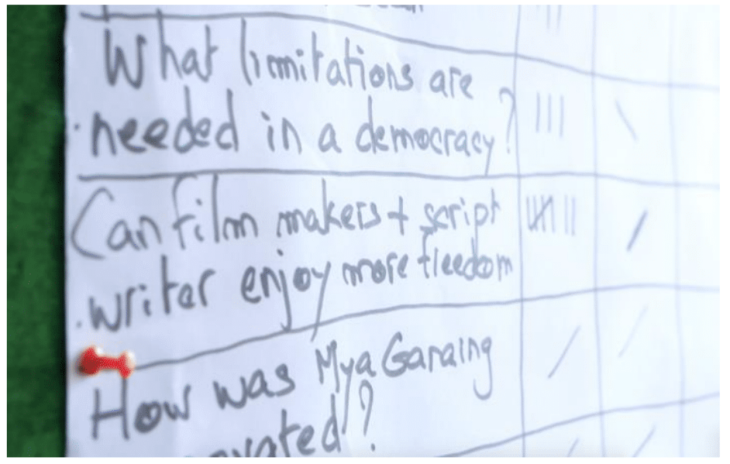

Two main threads stand out in the coverage of the festival: approaches to the event and its line-up were, on the one hand, overtly political and, on the other hand, thoroughly focussed on local, Myanmar-specific concerns. Participants’ reactions also point to a form of disconnect between the stage of the international film festival that served as the setting of the workshop and their own concerns. In interviews, participants stressed the importance of access to foreign films in Myanmar, meanwhile their articles questioned the festival’s overly international component that often made it inaccessible to local audiences. MEMORY!’s line-up consisted primarily of American productions: the “newspaper films” that are almost a sub-genre of Hollywood movies. Myanmar was only represented by one film (1934’s Mya Ga Naing, whose restoration MEMORY! contributed to in 2016), and few foreign films featured Myanmar-language subtitles, making them indecipherable to many. The students (some of whom spoke Burmese as a second language, and very little English) were quick to point out that lacuna. During a class discussion on freedom of expression, the conversation steered towards production and access to local ethnic media, which is a topic that MEMORY!, with their focus on worldwide heritage, could not adequately address. Yet ethnic representation is currently central to debates surrounding freedom of the press in Myanmar.

The Journalism and Culture workshop thus illuminates the interplay of the arts, the media and politics as they are apprehended by Myanmar’s civil society and its future journalists. As a site where local and international actors, imperatives and motivations intersect, it also provides a vantage point into the processes at work as the country’s transition towards democracy remains the object of international scrutiny, inputs and interventions. The MJI students proved to be extremely invested in an exercise that provided them with an opportunity to practice journalism early on in their school curriculum, in exceptional circumstances and with tangible results. To the surprise of their instructors, who recalled the previous year’s participants approaching the workshop and its politically-committed themes with more caution, this year’s cohort was willing to interrogate the sensitive topics head on. Students’ feedback on their experience was positive, as they reported not only a feeling of having improved their journalistic skills, but also one of responsibility as their words were about to be printed in a publication, albeit ephemeral, that was under their editorial control. Faced with a line-up of mostly foreign productions that occasionally seemed to fail to speak to local concerns, the participants used the festival’s focus on press and democracy to interrogate Myanmar’s own media and cultural policies. Thus transforming the profoundly international site of the film festival, with its assemblage of foreign and Myanmar-based social, political and cultural actors, into a springboard for local debate. In a rapidly changing society that is gradually opening to new influences, the decentralizing influence of the festival provides a genuinely democratic space for showcasing a diversity of ideas and opinions – even if those ideas, as evidenced by the students’ coverage, might not translate smoothly to Myanmar society.

Our goal is to show students that, despite their age and lack of experience, they can tackle topics that are ambitious or sensitive. We want to show them that to be a journalist is to be free. When you have ideas, when you have questions, you need to try and pitch those ideas, and not only write what your boss asked you to write. Being a journalist is not merely following other people’s ideas, we have a duty of putting ideas forward in order to make progress.

concludes instructor Jêrome Boruszewski. In a country where, as stated by UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar Yanghee Lee, the era of openness, transparency and the expansion of democratic space promised by the democratic transition is yet to be completed, the workshop offered participants the safe space of an international event to promote and build the durable and self-sustainable foundations of culture of independent journalism and critical inquiry. It illustrated the complexity of the current situation of the press in Myanmar, as journalists both present and future have to navigate their inroads towards freedom of expression and the more complex, and constantly shifting, reality that perpetuates the mechanisms of institutional and self-censorship.

Marie Puysségur is a recent graduate of the University of Cambridge’s Film and Screen Studies Masters programme.

Like This Article

December 18, 2024

March 20, 2024

February 12, 2024

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023