Shalini Perumal explores Myanmar women artists’ roles in times of political upheaval.

The digital age has revolutionized the way artists connect with their audiences and express their creativity. In Myanmar, the online realm has become a captivating canvas for artists, especially women, to showcase their creative prowess. The online world has offered women artists a powerful platform for self-expression, collaboration, and engagement with audiences both within and beyond borders. This digital revolution has not only propelled their works into the global spotlight but has also empowered them to transcend geographical boundaries, share their narratives, and challenge societal norms. However, the landscape shifted dramatically after February 2021, altering the dynamics of their agency on digital platforms. This analysis delves into the experiences of women artists from Myanmar, examining the evolution of their online presence before and since the coup.

In the decade of ‘democratisation’ before the coup, the art scene in Myanmar could best be described as an era of empowerment and expression. During this time after decades of military rule that came before, the digital space provided a haven for women artists to share their art, voice their opinion and connect with a global audience. Social media platforms, art-sharing personal websites, and online galleries became vital avenues for expressing their creativity beyond geographical boundaries. Pre-coup, platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter allowed women artists to showcase their artworks, engage with fans, and foster connection with the global art community. Artists like Pinky Htut (Pinky†u† 🌙 (@pinkyhtut) • Instagram photos and videos), who is also a musician, belonged to a generation that grew from the opening of Myanmar to the outside world since democratisation.

Virtual spaces are akin to curated exhibition halls, offering visitors an immersive experience into the artists’ world of colour, form, and emotions. Through vibrant visuals, thought-provoking narratives, and virtual exhibitions, women artists from Myanmar found a newfound recognition of their voice, wherein they could share narratives of culture, identity, and societal issues after 50 years of brutal military rule, when such forms of expression were carefully monitored and censored. The digital realm allowed artists to communicate their unique cultural and ethnic identities, fostering appreciation for Myanmar’s rich heritage. In the ten years that preceded the February 2021 coup in Myanmar, the country experienced a lively art scene, particularly in urban centres such as Yangon and Mandalay. Sculpture, puppetry, photography and digital art (spurred on by greater internet freedom) allowed Myanmar’s art by women to flourish. Painting Myanmar’s Transition, a book that spotlights more than 75 artists and their work, including numerous workers by women, sheds light on the power of democracy to allow art to flower, particularly in the form of resistance art. Yet, online spaces continue to draw more of an audience to an already growing art scene in urban centres. For example, “Art-Spaces”-Us” was a successful online exhibition that took place in April 2020, giving women artists showcased in the exhibition a collective space for freedom that can tell a multi-dimensional story. It allowed them to challenge gender norms, contributing to a shift in perception during this period.

Women artists also harnessed the power of online networks to engage in collaborative initiatives with fellow Myanmar and international artists to create cross-cultural dialogues. Additionally, many women artists used their online platforms to advocate for social and political change, addressing issues such as gender equality, human rights, and environmental concerns. With greater freedom in the ten years before the coup, women artists persevered and solidarity art also became common. Solidarity art is defined by Jacqueline Adams as art made by individuals experiencing state violence and economic hardship, which others distribute, sell, and buy to express solidarity with the artists and give them financial support.” (Book: “The Art of Solidarity”: 8 What Is Solidarity Art? (degruyter.com)). In an article that examines this topic, it is mentioned that women Myanmar artists often produced art, “then send the digital versions of these works overseas, where they are printed, hung, shown, and sold, with the proceeds returning to the artists who produced them, many of whom remain in Myanmar”, allowing women artists to hone their agency in e-commerce initiatives.

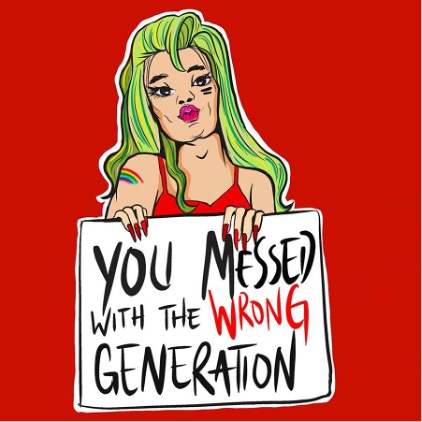

Once the coup came about in February 2021, women artists played an instrumental role in engaging in anti-coup forms of protests through art, documenting the creative and courageous expression of dissent through films, paintings, well-documented performative protests, subversive posters, dances and more, which was shared globally with the hashtag #WhatsHappeningInMyanmar. As the military government restricted the internet because of the wider revolutionary movement, this has an impact on the art scene’s anti-coup resistance. For example, Ku Kue, the first women graffiti artists in Yangon, created political art directed at the military. Her depiction of youth holding a sign that reads “You messed with the wrong generation” that made the rounds on the internet showcases the anger felt by youth who have been given a taste of democracy only to have it taken away from them. Her art has been showcased online across various IG pages including @girlpowerinmyanmar, a bi-lingual children’s book, for which she is an illustrator.

Other artists like Chuu Wai Nyein created art “with an aspiration of elevating and empowering Burmese women in a society where they had to endure harassment and abuse. So when the coup hit, it wasn’t altogether unsurprising that Chuu would use her artistic ability, combined with her values of social justice, to find a way to contribute in the early days of the resistance movement.” (Insight Myanmar, 2022: A Portrait of the Artist, After the Coup — Insight Myanmar) She also has her own website showcasing her resistance art.

Following the coup, the online landscape transformed into a space fraught with challenges, as political turmoil led to restrictions on internet access, social media censorship, and concerns over personal safety. Despite these obstacles, women artists have showcased remarkable resilience, adapting their online presence to navigate the evolving environment. Their digital agency post-coup included subtle resistance – with limited online freedom, women artists are using metaphors and symbolism to communicate their discontent and aspirations. Many artists turned to online platforms to raise global awareness about the situation in Myanmar, seeking support and solidarity from the international community. The digital realm has also become a sanctuary for preserving Myanmar’s cultural heritage, with artists utilizing online spaces to share traditional practices, folklore, and stories.

While the online presence of women artists from Myanmar continues to endure challenges, it also stands as a testament to their unwavering determination to overcome adversity. Their resilience showcases the transformative potential of digital platforms in amplifying voices, inspiring action, and preserving cultural narratives. As the political landscape evolves, the digital realm remains a beacon of hope for fostering connections, advocating change, and reclaiming agency, even if forcibly limited.

With the closure of physical art spaces in urban centres and persecution of artists like Pinky – who left Myanmar in Spring 2021 when her bandmate was arrested and his laptop confiscated – online spaces have become even more important for women artists and the resistance as a whole. The online journey of women artists from Myanmar is a narrative of empowerment and resilience. From thriving in a pre-coup era of creative expression to adapting to the challenges of a post-coup reality, these artists have demonstrated the power of digital platforms as tools for connectivity, advocacy, and cultural preservation. In a world where pixels meet passions, women artists from Myanmar are painting a tapestry of resilience, identity, and advocacy on the vast canvas of the digital realm. Through strokes of creativity and narratives that transcend screens, they are redefining the art landscape and leaving an indelible mark on both the virtual and physical words. Their stories remind us of the profound impact that art and digital agency can have in shaping narratives, fostering solidarity, and standing up against adversity.

In sum, technology, gender dynamics within digital spaces, and the interplay among art, identity, and online platforms is evolving. This article could shed light on the challenges, opportunities, and nuances that shape the experience of women artists as they navigate the digital landscape in the context of the February 2021 coup.

Shalini Perumal is a creative international development professional who has worked previously in Mae Sot, Thailand at Mae Tao Clinic, a charity that serves Karen and other Burmese migrants and refugees living in Thailand. She is currently a Communications Officer at ActionAid India in New Delhi. The views expressed in the article are her own and do not reflect those of the organisation. (X: @perumal_shalini and Instagram @shalini.sri.perumal)

Like This Article

March 21, 2025

December 18, 2024

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023