Reshmi Banerjee reviews an engrossing tale of family history, national politics and regional cuisine.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the loss of innumerable lives all over the world has made us suddenly more aware of the comforting embrace of family ties. It has made us realize the importance of shared memories and the ever-lasting reassurance that surfaces from a sense of familial belonging. Burma: Food, Family, and Conflict explores the fascinating journey of a family in Burma, combining personal narratives with regional food recipes that include the authors’ family favourites. Readers are provided with not only a summary of the historical saga of Burma from colonial to postcolonial times, as experienced through the prism of a family, but they also get a glimpse of Myanmar’s culinary diversity—which seems delicious!

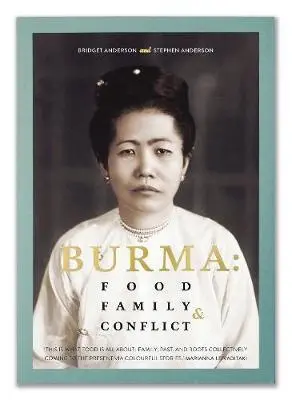

The authors also present us with beautiful family pictures and mouth-watering images of food, which keeps readers engaged until the book’s very end. Tape recordings of their grandmother, ‘Grandy,’ along with historical research, has helped in sketching the life history chronicled in the book. The book also provides a critical reminder that food not only helps us to stay connected with family and friends but continues to be an important instrument for cultivating nostalgia and sharing heritage. Moreover, widespread migration and inter-mingling in South and Southeast Asia has created a melting pot of traditions (cultural and gastronomic) thus generating a panorama of relatable commonalities which is evident in the book.

The authors (who are siblings) tell a gripping story of their grandmother, Daw Saw Yin, and her family in Rangoon. Her father William Carr was an English judge married to a Burmese lady, Ma Khin. The book begins with a description of Daw Saw Yin’s parents’ early married life, the family tree (in England and Burma), life in Moulmein and Bassein, the outbreak of the First World War and, finally, her boarding school years in Rangoon. Through this narrative, the reader is informed about the various social attitudes and challenges that were prevalent in that time. For example, the fact that her independent mother had her own stall in the Daingwunkin bazaar was not considered strange, as women always worked in Burma. The reader also learns of the language divide between the English and the locals (a barrier which existed within the household, too), and about the debt-ridden cultivators, reflective of racial cum economic complexities within the country, along with the apparent social unease and ambivalence that existed within her mixed cultural household. However books, festivals and food continued to be celebrated and provided an amiable environment. By the second chapter, the authors also successfully make us relish the recipes in the book, which include Mon prawn curry, fried pork ribs and Simnel cake, amongst many other delightful and exquisite dishes.

The book straddles skillfully between the personal and the political. On one hand, it describes a lovely family holiday spent in Kalaw in 1918, a sea voyage to England, Daw Saw Yin’s English education years, and, later, her return to Burma in the 1920s. On the other hand, it delves into the political tensions associated with dyarchy, the dismantling of the sangha and the rise of nationalism back home. The authors describe how, after returning to Burma, their grandmother began to lead two lives: one at home and the other at Rangoon University, symptomatic perhaps of the disjunct existing between the private and the public spheres. Meanwhile the recipes provided of Khao Swe, lamb biryani, Shan fish cakes and Pavlova with raspberries contribute immensely to keeping us glued to the family story. It makes us hungry for more, both literally and metaphorically.

Daw Saw Yin’s life took a different turn during her university years, where she not only acted in plays and wrote for a magazine, but also became more politically aware. This phase of her life is engrossing, with interesting experiences ranging from her chance meeting with J.S. Furnivall in the university bookshop, to falling in love with a young tutor from the English department. Her journey back to England for higher education in University College, London and her attendance as a guest in the inaugural meeting of the Burma Round Table Conference—against the backdrop of political turbulence impacting Burma in the late 1920s and early 1930s—provides us with an understanding of her ever-expanding canvas in life.

The authors take us deeper not only into their grandmother’s journey, describing her married life, children and teaching in Rangoon University post-marriage, but they also lay out the rapid changes occurring in Burma with the strikes of the 1930s and the discrimination against Indians, effectively capturing the sense of fear and insecurity of those years. The fast-paced, compelling account is accompanied simultaneously by the detailed recipes of spicy sausages, Balachaung and Mahogany Beef Pie provided in the book.

The Second World War and the movement of thousands of people, in extremely difficult circumstances, across the border into India are described well. Daw Saw Yin herself had to move to India (Calcutta) to start her new life. Her move later to Delhi and her life—including her work(in the All India Radio where she met Aung San—and her family, including the loss of her father, tell us of the adjustments that she had to make during a short period of time. Her world was constantly changing, but there was a feisty and hopeful spirit with which she embraced it all. Burma also adapted to strong winds of change, with the country gaining independence and continuing on its own trajectory. The book ends with the authors visiting their old family home in Kalaw in 2006, where reminiscence is matched with pragmatic discussions on current challenges facing Burma. 2014 also saw Stephen Anderson (one of the authors of the book) inaugurate the Ma Khin Café in Valencia, named after his great grandmother.

The book is an ode to love —love for a grandmother whose life was an inspiration. It is reflective of the fact that every person’s journey, with its periods of joy, disappointment, struggle and resilience, creates a kaleidoscope from which we can learn. The book creates a strong visual impact on the minds of the readers, rendering it an absorbing read. The mix of food recipes along with imagery makes the text creative. While reading, I looked forward to not only knowing more about the endearing Daw Saw Yin, but also of discovering Malabar fish curry and mushroom korma which turned out to be my ‘piece de resistance’.

The book also brings forth some current unresolved but relevant concerns about Myanmar through its historical and personal family narrative—issues of social norms, racial discrimination and exclusion, power/gender equations and about people caught at the borders in a crippling state, which still continue to trouble the country today. The past has seamlessly permeated into the present: not only in our minds in the form of memories of a loved one but also in the daily challenges that we continue to tackle.

Reshmi Banerjee is a research fellow at the Institute of Social Sciences in New Delhi. She was previously an Academic Visitor in the Modern Burmese Studies Programme in St Antony’s College, University of Oxford and a research associate in SOAS, University of London. Reshmi is a political scientist with an M.Phil & Ph.D from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. Her interests include conflict over resources and identity, political economy of borders & Diasporas.

Like This Article

December 27, 2023

September 05, 2022

November 25, 2021

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023