Dinith Adikari and Michael Dunford explore the role of the aphyaw hsayar and the challenges they face in today’s tea market.

The following is a snapshot from the field observations of Mike Dunford and Dinith Adikari, both PhD students in Anthropology at the Australian National University. Dinith’s primary focus is the changing social functions of tea shops, and Mike’s research focus is on the tea industry’s ethno-political and ecological entanglements. The observations that form this post were made between January 2018 and March 2020, primarily in Yangon and Mandalay.

This post is a brief meditation on the role of the aphyaw hsayar (အဖျော်ဆရာ), a term we are choosing to translate as “mix master.” Most Tea Circle readers will be familiar with laphet yay (လက်ဖက်ရည်), the milky tea served at tea shops throughout Myanmar: the aphyaw hsayar is the person—usually a man—in charge of blending laphet yay to customers’ tastes. Aphyaw hsayar are everyday experts on the level of baristas or skilled bartenders, marshalling a variety of ingredients to produce cups of tea that match the vast range of possible tea orders available in a Burmese tea shop. A talented aphyaw hsayar can cultivate a following and make a tea shop; by the same turn, losing a talented aphyaw hsayar can be ruinous. As Myanmar’s tea culture changes, especially in Yangon where dedicated aphyaw hsayar seem to be in decline, there is some evidence that tea-mixing may be a dying art. We would like to explore the role of the aphyaw hsayar further and ask what it means to mix tea in today’s teashops.

An aphyaw hsayar’s workday begins in darkness. Although there is slight variation in the specific techniques employed in each tea shop, the general rhythm is the same: extremely strong black tea is prepared through the night over a wood or charcoal fire, usually with a little bit of added salt; this tea then steeps or simmers for up to ten hours. The tea must be ready in time for the morning rush of people looking for breakfast. The base liquid must be concentrated enough to provide a powerful caffeine kick, but not so much as to be too astringent and harsh. When customers want weaker or less astringent brews, this base liquor is titrated with water.

Different tea shops employ different methods to make sure that they never run out of the deep-brown base liquor. In Aung Tea Shop in Yangon’s Kyauktada Township, the black tea is usually ready to drink by 5:00 a.m., then segmented into insulated canisters to help manage distribution throughout the day; in Mandalay’s famous Kyaing Thin, the aphyaw hsayar always has at least one backup kettle warming on the burner, in case supplies begin to run low. In the massive 24-hour tea shops found in major cities, the aphyaw hsayar will keep pots of tea simmering day and night to ensure that the supply never goes dry.

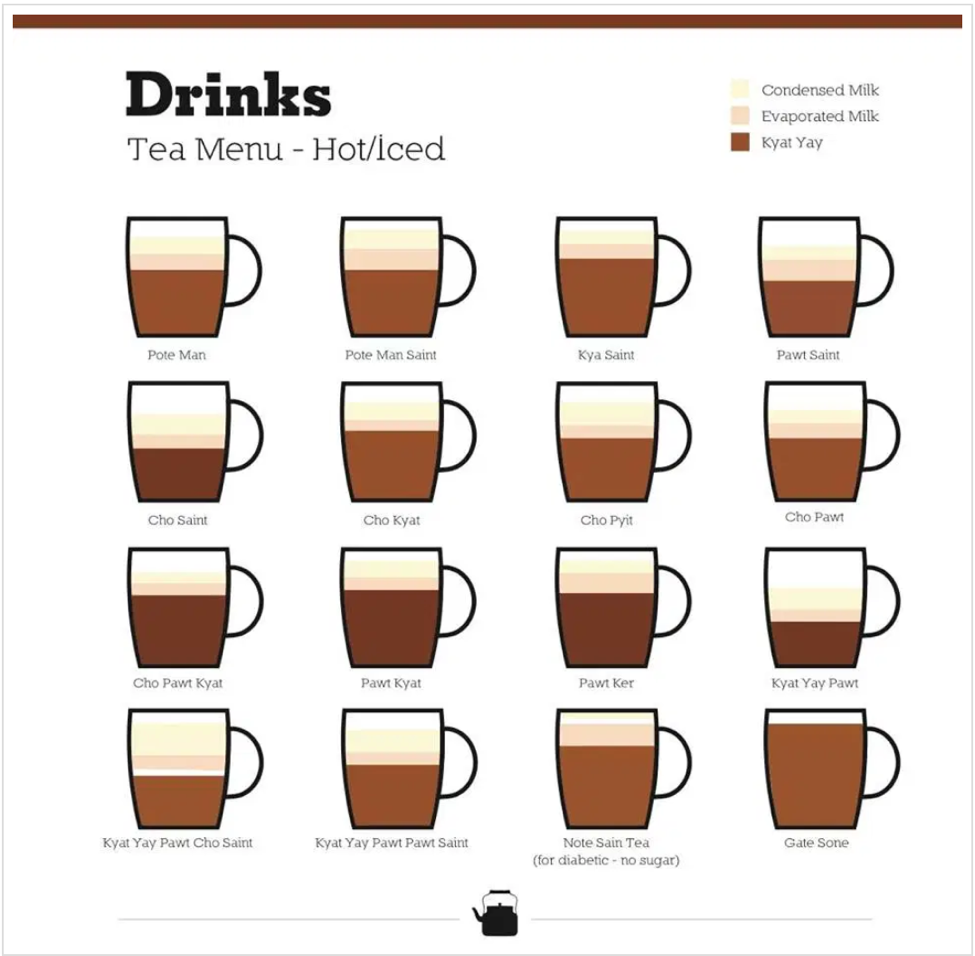

The aphyaw hsayar’s palette consists of six main elements: 1) highly concentrated black tea, 2) sweetened condensed milk, 3) evaporated milk, 4) hot water, 5) granulated sugar and 6) normal cow’s milk. In certain tea shops, malaing (မလိုင်)—clumps of yogurt-like curdled milk—can also be added as a special treat. If a customer orders a pon man (ပုံမန်), or “standard” cup, they’ll receive tea that has been diluted with water and mixed with both evaporated and sweetened condensed milk; the result is very sweet and creamy. Yangon’s Rangoon Tea House—less a tea shop than a high-end Burmese restaurant—has compiled a diagram of most of the possible tea orders, ranging from most diluted to least diluted:

Over the course of 2018, Mike—and a team of students from Yangon’s Parami Institute—tried to learn how to correctly make a cup of tea from an experienced aphyaw hsayar. Simply brewing a consistently repeatable pon man (ပုံမန်), or “standard” cup, took them about three days of trial and error, despite receiving a written recipe from the aphyaw hsayar; mastering the vast range of possible tea orders is a skill that would likely take months of practice.

Daw Nge Nge, the aphyaw hsayar who taught Dinith how to make tea, simplified the process for him, but it still took some time to get it right. For example, a cha sein (ကျစိမ့်), or strong and rich tea, started off with half a teaspoon of sweetened condensed milk; the cup was then filled with 1/3 evaporated milk and almost 2/3 black tea, with just a splash of water. She mentioned the process of making the cha sein as follows.

“A little condensed milk, a little evaporated milk, a little black tea, a little more and finish with hot water.”

When Dinith mentioned the difficulty of making tea, Daw Nge Nge laughed, and said:“It is not hard but takes a lot of practice!”

A skilled aphyaw hsayar would not only need to know these ratios like second nature, but also be fast enough to make multiple cups at a time.

The teashop workforce is transient, particularly in Yangon, where many workers come from villages or smaller towns (especially from Ayeyarwady Region). These workers generally receive low pay, meaning they often leave their jobs if better opportunities come up or the pull of home draws them to their villages. Although trained, dedicated aphyaw hsayars might make more money than unskilled staff, their wages are still fairly low, and they are not immune to the highly competitive labour environments in Myanmar’s major cities: any Yangonite who regularly attends a particular tea shop will be familiar with the rotating cast of employees from various places across the country. This transience—and the extremely competitive economic space that tea shops occupy—means that the time invested in training people to mix teas can often be for nothing as tea shop workers move on.

In some cases, a tea shop owner might decide to fire a dedicated aphyaw hsayar and ask an unskilled, lower-paid employee to mix tea. This could be a highly risky tradeoff for tea shop owners: there are many anecdotal stories of an entire tea shop’s customer base moving when a particularly good aphyaw hsayar changes shops or establishes their own. On the other hand, new tea shops will be forced to compete with established ones for customers, and may temporarily hire a skilled aphyaw hsayar to ensure that the tea is impressively good when the shop opens. Whether or not this aphyaw hsayar sticks around over time is subject to the whims of the manager.

Aphyaw Hsayar present tea as reflections of the spaces tea shops occupy. While not intending to portray broad strokes of tea shops in Yangon, there are some noticeable changes in how people use the tea shop space. The range of tea shops is broad, but there seems to be a broader movement which blurs the line of a tea shop (for the primary consumption of tea and snacks) with restaurants (for the primary consumption of meals). These latter, restaurant-like tea shops are often part of chains, and present a space where a person can do most things (such as eat and drink tea) but the same social connotations do not necessarily exist. Tea in this case is a secondary purpose for these spaces and as a result in these shops, mixing tea is placed in the hands of the customer, who orders a tea with its components assembled in a cup and a spoon to mix the concoction together.

When asked about this, Daw Nge Nge, the aphyaw hsayar mentioned earlier, said, “It is easy to make tea this way. I can make tea fast and the customer can mix the tea together.”

The cup of tea in this sense has larger margins of error for taste, and the drinker can control the flavour of the tea as well, to a certain degree. It shows that the drinking of the tea is less about the flavour and more about what else the cup of tea provides; a cup of tea could buy a customer nearly unlimited time to hang out in a tea shop, but, in such cases, tea-mixing itself has become less the job of the aphyaw hsayar than the job of the customer, as part of a meal in between other work commitments.

Mandalay and Yangon have slightly different tea scenes. Although Mandalay has its share of giant, food-focused tea shops, there is still a strong prevalence of establishments that focus primarily on tea. Recently-reported changes in Myanmar’s tea culture have hit Yangon harder than Mandalay. In Mandalay, shops focused mainly on the selling of tea are crowded late into the night, mostly with men, drinking cups of steaming tea pulled by the aphyaw hsayar. Mandalay’s higher rate of laphet yay consumption is possibly reflected in the higher price of tea in Mandalay, despite its close proximity to Shan State’s tea fields. Laphet yay in Mandalay rarely costs less than 500 kyat per cup, and frequently more; in Yangon, by contrast, some of our informants expressed indignation at the thought of a 500 kyat cup, seeing it as excessively expensive.

The aphywaw hsayar has been an integral and highly skilled individual in tea shops across Myanmar. We are hesitant to call it a “dying art,” but it is true that recent changes in Myanmar’s labor economy have led to a decrease in the number of dedicated tea-pulling specialists. The emergence of the novel coronavirus pandemic—and the lockdowns that have followed it—will further complicate the lives of all precariously employed workers in Myanmar, including the employees of tea shops. Tea shop revenues have been flattened by as much as 70% in the wake of pandemic lockdown measures; the lively communities historically fostered by tea shops have also been circumscribed by “take-away only” policies or the construction of physical barriers between customers. Still, if any of our readers are lucky enough to find a tea shop with a skilled aphyaw hsayar, we urge you to support their trade! We strongly recommend ordering outside of the standard pon man or cha sein script: try a bracing pan cho, or a richly milky pon man sein. You will be able to experience one of Myanmar’s homegrown specialties.

Dinith Adikari is a PhD Candidate in Anthropology in the School of Culture,History and Language at the Australian National University. He recently completed his fieldwork on teashops in Downtown Yangon. His research asks how social spaces facilitate and are facilitated by everyday social practices.

Mike Dunford is also a PhD candidate in Anthropology at the Australian National University. His research asks how ethno-political relations and ecological practice shape northern Shan State’s tea economy. Prior to his time at ANU, he taught anthropology at Yangon’s Parami Institute.

Like This Article

November 22, 2023

July 18, 2022