Michael Edwards asks how to navigate Yangon using a transit map of Seoul.

A version of this piece first appeared at The Christian Nation Project. By examining different images and imaginations of the “Christian nation,” the project aims to broaden definitions of religion, politics, theology, and citizenship.

In 2016, Henry Van Thio, a Chin Christian, was sworn in as one of Myanmar’s two vice presidents. While nationalist groups protested the appointment, a Buddhist friend of mine expressed more muted concern. He could see the new NLD government was trying to appear inclusive, he said. But still, something didn’t sit right: ‘It’s like having a Buddhist as president of Italy or Iran.’ Embedded in this reaction was a feeling that certain nations have specific religious identities, determined perhaps by demographic facts, historical processes, constitutional arrangements, or some combination of all three.

Myanmar, for my friend, was one such nation. The country’s constitution famously skirts the matter, enshrining Buddhism’s ‘special status’ while recognising the presence of select other faiths. Concern for minorities tends to prompt calls for more secular arrangements that dismiss the ‘Buddhist nation’ as an exclusionary fiction. It’s curious, then, that at least some Christians in Myanmar decline to endorse such a move. For them, the Buddhist nation – like the Christian nation or the Muslim nation, for that matter – is not some abstraction or aspiration conjured by nationalists; such entities fundamentally exist, and their existence goes some way to explaining the world these Christians see around them.

This became clear to me on the bus, of all places. During fieldwork in Yangon between 2014 and 2016, I spent a lot of time riding the bus, often with my friend Suan, an evangelist at a church called Hope.* Like other Pentecostal churches, Hope saw opportunities for evangelism in Myanmar’s nascent democratic opening, with its easing of censorship and relaxation of restrictions on assembly. This was a moment, the thinking went, when God was on the verge of saving Myanmar, rescuing it from fifty years of military rule, just as he would bring its Buddhist-majority population to Christ. By sharing the gospel with Buddhists, evangelists like Suan worked with God towards these twin goals of political and personal salvation.

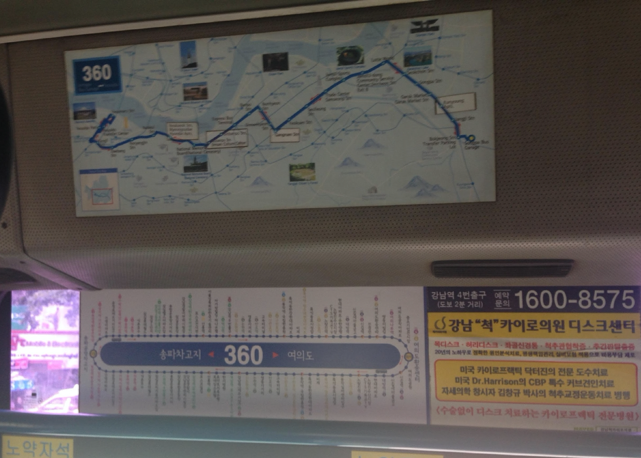

Suan was responsible for managing Hope’s evangelism program in Thanlyin, a township about 20km from downtown Yangon, over the south side of the Bago River. The trip from the church involved three different buses, and sometimes took several hours, much of it stuck in the city’s notoriously bad traffic. Many of the buses were second-hand imports from South Korea, upon which the new Burmese owner would often retain the original advertisements: posters for South Korean products that current passengers were unable to buy, written in a language few were able to read.

Also unchanged were the transport maps that informed commuters about the route the bus had plied in its previous life in Seoul, not about their present journey through Yangon’s congested streets. Riding these vehicles thus engendered a spatiotemporal dissonance: by traversing an overlapping set of actual and imagined routes, they ferried passengers across one urban landscape, even as their commercial and cartographic traces called attention somewhere else.

And not just anywhere else. Alongside their Buddhist compatriots, Pentecostals like Suan have been swept up in the Korean Wave, the exported world of K-Pop hits and Korean soaps. But the figure of South Korea carries extra meaning for Pentecostals – members of a Christian minority thought to make up less than 10% of Myanmar’s population – by virtue of its perceived status as a ‘modern’, and importantly, ‘Christian’ nation. With echoes of Weber’s thesis, this figure stands in juxtaposition to a belated Myanmar whose unyielding Buddhism, even in the face of two centuries of mission work, has left it ‘fallen behind’ (nauk kya deh) – stuck at an impasse, like a bus idling in traffic.

What the maps of Seoul’s transport network indexed was a Christian nation existing not just in a different place, but a different time: a past future, a future past. Frankly unhelpful as aids for navigating the city, they functioned more as maps for navigating time. They were maps to an alternative modernity Pentecostals felt the military government had long denied them – one characterised by the unobstructed circulation that would render Myanmar as open to the flow of goods, information, and traffic, as it was to the flow of the Holy Spirit. This was the vision they were now being promised, and, as elsewhere, roads were a fertile ground for an affective landscape upon which promises of the nation’s progress were met with a combination of anticipation and scepticism.

Anthropologists have documented the ways in which Christianity, and Pentecostalism in particular, orient people either towards or away from the nation. In some cases, Christianity seems to deepen believers’ investment in the nation, either by situating its redemption in a broader struggle between God and the devil; by reconfiguring political leadership as religious mediation; or by inculcating a sense of Christian citizenship that places the ‘weight’ of the nation on the shoulders of believers. In other cases, Pentecostalism has the opposite effect, engendering a ‘negative nationalism’ wherein the Urapmin, for example, are said to ‘cast their lot in with the white transnational Christian community that will, the narrative asserts, ultimately allow them to escape their national identity’. At times Christianity offers the means by which marginalised groups reimagine themselves belonging to a transnational community that is inescapably ‘foreign’.

Pentecostals in Myanmar, amidst the country’s fraught ‘transition’, expressed a complex attitude towards the nation. ‘Our church is standing for the nation,’ Sangpi, one of Suan’s colleagues, once told me. ‘This is why we pray every month, “God, give us good leaders”. Now the military is transferring power. If the church is strong, the country will be strong. Just look at Yonggi Cho in South Korea.’ The story was that Hope’s founder had been inspired by Cho’s Yoido Full Gospel Church, the largest congregation in the world.

But if South Korea’s Christianity could inspire, it could also explain. ‘Why is Myanmar so poor and South Korea so rich?’ Sangpi once asked rhetorically. Myanmar had an abundance of natural resources while South Korea had none. The answer was that, where South Korea had opened itself to God, Myanmar had closed itself to Him. Lodged inside the causal logic of karma (kan), people had shut themselves off from the unfathomable workings of grace (che zu daw), just as Myanmar’s military leaders had closed the country to the world, and just as Yangon’s traffic was frustrating the smooth circulation visualised in the streamlined maps of Seoul’s public transport network.

The colonial encounter in late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century Burma threw up what Benedict Anderson called the ‘spectre of comparison’. Subjugation by the British engendered a sense that Burma, formerly a proud Buddhist kingdom, had ‘fallen behind’ (nauk kya deh) other countries. According to a widespread telling, independence in 1948 brought about a period when the country managed in some ways to ‘catch up’, albeit one also marked by armed insurgency, but this lasted only until the coup in 1962, which threw it again off course. Myanmar’s progress is thus tracked against a trajectory apparently unfolding smoothly elsewhere. It is out of sync with this unfolding, but also, at times, on the brink of dropping back into its flow. For Pentecostals, the figure of South Korea looms large in this telling, a spectre of a ‘Christian nation’ in a comparative politics of desire and disappointment.

The ‘transition’ threw all this into sharp relief. God was now moving in Myanmar, believers maintained, notwithstanding the indifference with which their evangelism continued to be met. He had a plan for the country in which they placed their trust. But there was mounting evidence that Myanmar’s path to salvation was unlikely to be straightforward: new restrictions on expression; a crony class entrenching its economic power; and the amplification of longstanding currents of Buddhist nationalism, rendering precarious the position of non-Buddhists – particularly Muslims – and playing out most shockingly in the state’s treatment of the Rohingya.

Early 2017 saw an overhaul of Yangon’s bus system, which serves about 2.8 million people each day. This followed the arrival, in February 2016, of a new fleet of bright yellow, air-conditioned Bus Rapid Transport (BRT) vehicles. Cool, fast, and clean, they were a world away from the rattling imports with their incongruous route maps, their irrelevant advertisements, and their tendency to break down. Believers like Suan and Sangpi described the new buses as a ‘blessing’ (kaun chi), their introduction a step towards a national salvation in which political opening would be accompanied by an opening to God. Some read Henry Van Thio’s appointment in similar terms. For now, though, the South Korean buses remained on the streets, relics of a lingering past and an elusive future. Their presence marked an absence, reminding believers of a distance that still needed to be traversed, a gap between a putatively Buddhist nation and a putatively Christian one.

Michael Edwards is Smuts Research Fellow at the Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge

Like This Article

August 29, 2024

February 22, 2024

November 22, 2023

May 15, 2023