Courtney T. Wittekind and Hilary Faxon underscore threats posed by a new market for land on Myanmar Facebook.

Myanmar’s economy has seen a dramatic downturn in the aftermath of the 2021 coup, with figures suggesting a contraction of at least 30%. Yet, even as households return to a state of “everyday economic survival,” to borrow a phrase from political scientist Ardeth Thawnghmung—with news outlets reporting rising unemployment and starvation—Myanmar’s real estate market has surged in both popularity and pricing. Industry reporting and coverage in national media suggest that market rates for land and property have doubled, and even tripled, in some areas—a statistic that underscores what has long been true in Myanmar: for many, land is the most reliable စုဗူး or savings jar.

Since the coup, the instability of other assets has buttressed peoples’ beliefs in the stability of investments in land. The value of the Myanmar kyat has fallen by nearly half, even as the junta has effectively banned foreign currency. Gold prices spiked to a record high of over 3.5 million kyats per tical last August. Investments in cars, another established asset in Myanmar, have dropped off, mirroring global trends that reflect pandemic-era supply chain disruptions and, more recently, sky-high gas prices. But, if land remains one of a very few ways to store value in Myanmar’s unfolding crises, important issues linger: Who buys land, who sells land, and how? These questions are perennial insofar as they intersect with historical dynamics of property and inequality. Yet, the current context also demands understanding how and why the land market—like Myanmar’s population more broadly—has increasingly migrated online.

Since 2019, we have conducted in situ and digital ethnography to trace shifts in land transactions as they moved onto social media. While brokers have, historically, swapped land documents, contracts, and cash around tables in teashops or in front of township land registration offices, during COVID-19 lockdowns, many began to advertise online. While the actors brokering land deals remain largely the same, their methods have transformed. Facebook—Myanmar’s dominant social media platform—has become especially popular as a tool for buying and selling land. We followed brokers, sellers, and buyers as they created or joined new pages and groups devoted to the sale of land. We reviewed dozens of rapidly growing public groups across Myanmar, many hosting tens of thousands of members, focusing on real estate groups that specialized in land sold in peri-urban Yangon, where plots of all sizes were in high demand as investments in proposed “new city” areas. Through close analysis of the advertisements and commentary in these groups, as well as interviews with group members, we charted the booms and busts of an unruly online property market. Our open-access article, recently published by Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography, shows that these digital activities have remade Myanmar’s land market in four significant ways.

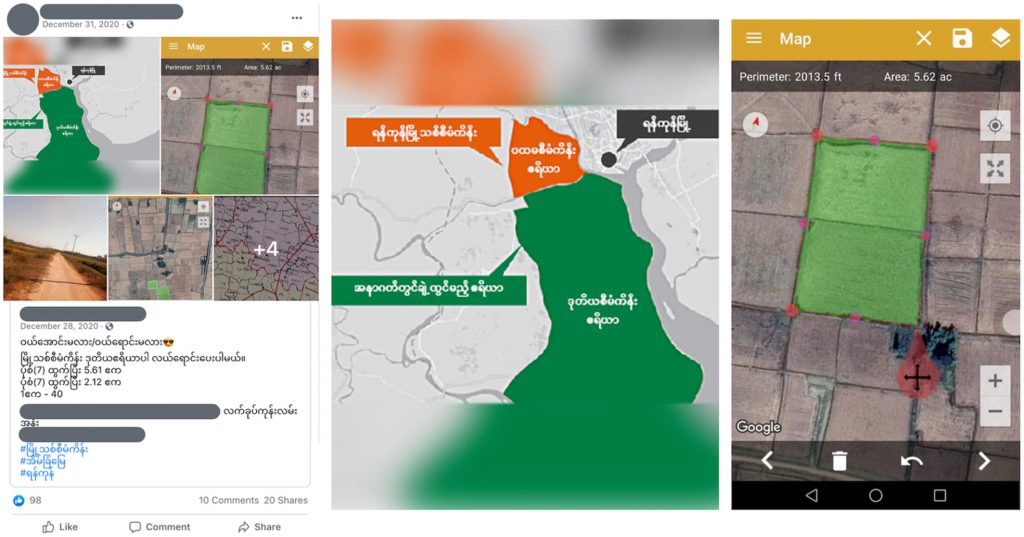

First, Facebook activity drove shifts in how land is used and valued. While land has always been bought, sold, and traded in Myanmar, it used to be a slow, intimate, and illicit affair, conducted on the black market in the context of close, trusted relationships and largely for livelihood purposes. As Stephen Huard has explained, in Myanmar, land is conventionally tied up in personal relations of inheritance, obligation, and stewardship, above and beyond the law. Ownership was rooted in the responsibility to maintain land as a source of ongoing security—a task which usually involved maintaining its capacity for agriculture. On Facebook, however, advertisements rarely discussed the land’s suitability for farming; instead, and especially in the coming “new city,” plots were promoted to far-flung businessmen and investors who, as one commenter asserted, “will never farm there.” Rather than noting soil quality, access to water, or elevation, Facebook’s land brokers instead highlighted details such as the distance to special economic zones, deep seaports, and other nearby projects, assuring potential buyers that soon-to-be developed, peri-urban areas were sure sites of profitable investment. Such transformations are in line with larger patterns of speculative urbanization across Asia, but we demonstrate how Facebook posts, photos, and real-time interactions accelerated the transformation of rice paddies into real estate.

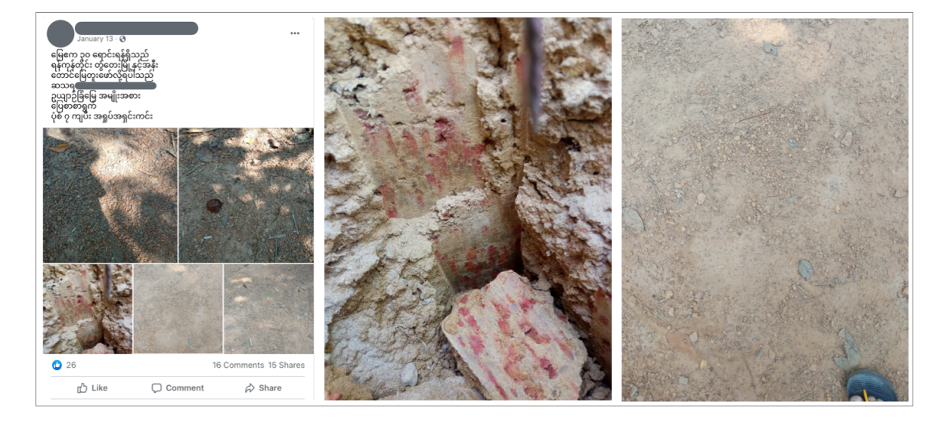

Second, Facebook expanded the scope of the land market, drawing in more people, in more places. Historically, research on brokerage in Myanmar has underscored the personal form of guarantee central to brokers’ work. Trusting a broker has long required clients have confidence in an individuals’ dependability and expertise in navigating a poorly regulated real estate market, rife with false documentation. One-to-one brokerage relationships were epitomized by bonds of trust, developed within close-knit familial, social, and geographic contexts. Yet, on Facebook, we observed that these intimate ties have splintered into a series of broader and more depersonalized online associations, what social media scholar danah boyd calls “networked publics.” On Facebook, middle-class, often first-time, buyers can browse listings for investment in peri-urban Yangon or a cool weather retirement in Pyin Oo Lwin. They look not only to brokers for assurance; instead, they rely on a collective perspective shared by Facebook group members that certifies the prudence of a purchase, posting queries about proper procedures and lucrative parcels. Meanwhile, brokers post images of sellers’ legal documents and piles of cash as evidence of legitimate and successful sales, branding their businesses to ever-expanding publics.

Third, brokers’ activity on Facebook amplified the urgency and speed of transactions. Price was no longer primarily based on the labor of a particular broker working to flip a single plot, but rather on a frenzy of hurried, online interactions. Increasingly, those we interviewed—buyers, sellers, and brokers, alike—struggled to “keep up” as more and more land was exchanged, at higher and higher prices. As one real estate agent we interviewed put it: “At the very beginning, there was a lot of land and a lot of people wanted to sell and cash out, and at that time, the price was cheap. And then, they started doing this on Facebook, and the price went up super high.” By January 2021, the month prior to the coup, many brokers we interviewed wished the land market would slow back down. Combined with land’s transformation into an asset and the expansion of brokerage, these rapid transactions enact what we call “networks of speculation.”

This brings us to a final, and perhaps the most significant, shift; Facebook intensified risk for those with the most to lose. Over the course of our research, we watched as farmers and other precarious landowners, first-time investors, and petty brokers all sought to weather the land market’s booms and busts, as land that would have barely garnered US$2,000 in 2018 had was suddenly selling for US$25,000 in 2020. Sellers rushed to liquidate to avoid missing out; brokers found that the speed and intensity of the Facebook land market was too much; buyers worried prices would crash before they could resell the high-value plots they had amassed. Ultimately, we found that the volatility of unregulated transactions intensified danger for all but the wealthiest investors involved in these Facebook-based markets. While Myanmar’s unregulated and often illicit land market has always been risky, Facebook raised the stakes for those unable to “wait out” the market’s booms and busts, and the reach of the platform enlisted a larger and less well-resourced subset of the population into sales that stretched far beyond trusted contacts.

This final point is all-the-more critical in the wake of Myanmar’s 2021 coup and the resulting economic collapse, which, together, have set off a real estate boom driven by fear, specifically the lack of confidence in Myanmar’s military-led financial institutions. Frontier has reported that after banks eased restrictions on withdrawals, many in Myanmar chose to redirect their savings from bank accounts and into land holdings. For those without established relationships with a trusted broker, or with little confidence in their ability to navigate the land market on their own, Facebook has become the predominant platform for seeking out available plots as well as experts who can guide new investors’ purchases. Our current work is tracking the rise of scams in Facebook-mediated land markets.

This inadvertent manifestation of platform power presents a new twist on generic global stories about digital transformations in property, which tend to focus on sites explicitly designed for renting, buying and selling (think Zillow or Airbnb). Crucially, and for the reasons our article underscores, brokers’ creative re-appropriation of the platform for buying and selling land exposes users to greater and more far-reaching risks. How Facebook’s role in Myanmar’s land market could be shifted to ensure—rather than undercut—forms of stability being sought by Myanmar’s majority is a critical political question for platforms and for their users, in and beyond the country. As the resistance seeks to shatter the military’s hold on land and resource wealth and most people struggle to stay afloat, online buying, selling, and speculating is shifting the ground beneath their feet.

The research upon which this article and Tea Circle post is based was conducted with the support of multiple collaborators based in Myanmar, who prefer to remain anonymous at this time. We are very grateful for their time and insights.

Courtney T. Wittekind is a Postdoctoral Associate at Yale University’s Program in Agrarian Studies, where she researches new forms of real estate speculation emerging in Myanmar and, particularly, in peri-urban Yangon.

Hilary Faxon is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Social Science at the University of Montana and a Marie Curie Fellow at the University of Copenhagen. Her research investigates land politics in Myanmar and environment, development, and technology in Southeast Asia.