This is Part 1 of a two-part interview with the newly appointed Minister of Human Rights for the National Unity Government, U Aung Myo Min.

This post is part of a collaboration between Tea Circle and the Institute for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University to share transcripts and reports from a series of seminars on Myanmar that ISHR is hosting.] Selections from this interview have been translated into Burmese.

Read Part 2 of the interview here.

Thursday, May 13th at 10:30 EST/20:00 IST/21:00 MMT

Kristina Eberbach: In response to the coup that took place 102 days ago, the Institute for the Study of Human Rights (ISHR) began organizing a series of webinars focused on human rights and democracy in Myanmar. We are planning a number of further webinars over the coming months with leading Myanmar and International activists, academics, and policy-makers. To receive additional information about upcoming events in this series, please sign up for our newsletter at humanrights.org

My name is Kristina Eberbach, and I’m Deputy Director of the Institute and adjunct assistant professor at SIPA. I’m also the co-developer and co-director of the Institute’s University Human Rights Education in Myanmar.

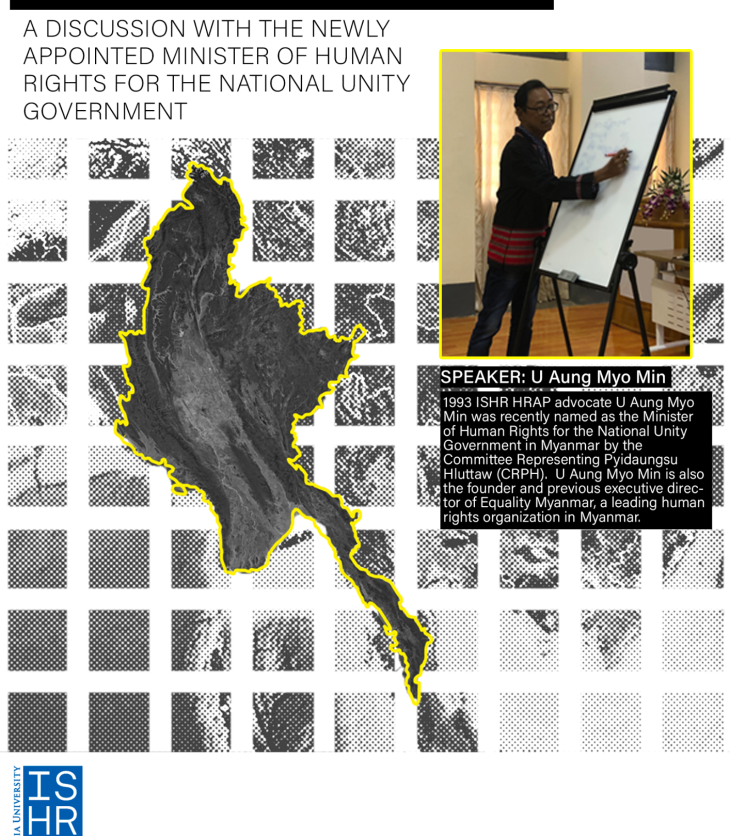

I’d like to welcome U Aung Myo Min, who was recently named Minister of Human Rights for the National Unity Government in Myanmar by the CRPH (Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw). He is a long-standing human rights advocate and was a student leader in Myanmar’s 1988 revolution. He is also the founder of Equality Myanmar, a leading human rights organization in the country, and has been awarded seven international awards for his work in human and LGBT rights. In 1993 he also participated in ISHR’s Human Rights Advocate’s Program and we have had the pleasure of collaborating with U Myo and EQMM as part of the Institute’s University Human Rights Education in Myanmar program and SIPA’s capstone program.

I’d also like to introduce my colleague Ben Fleming, who will be co-moderating this discussion. In addition to co-developing and co-leading our Human Rights Education in Myanmar initiative, he is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) and an Adjunct Professor at South Texas College of Law Houston.

Ben Fleming: Hey everybody, thanks, Kristina. Sayar Myo, good to see you, welcome everybody, and Mingalaba.

Kristina Eberbach: How did the formation of the ministry come about within the NUG? Can you describe for us the relationship that you believe will exist with the NUG and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint if/when they are released? And finally, what is your envisioned role in this position?

U Aung Myo Min: It’s a good question. The NUG was founded by CRPH, a composition of the elected members of Parliament in the 2020 elections. The military did not want the Parliament to set up a new government according to the procedures. So they took a stage, staged a coup before the new government was founded. The first thing they did was arrest Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the President, and many other cabinet members. They are still under arrest right now, but the CRPH was brave enough to set up their interim government. It is just for the legislation process. We needed the executive body to make to prepare us. Since the state counselor and the President are under arrest, we did not have any communication. But the CRPH thinks this is the right move to act as a legitimate government because they are the legitimate members of Parliament, and they have a duty and responsibility to set up a legitimate government.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was not in the consultation during the formation of the NUG, but she heard about it through other sources. She didn’t say anything. The new stance of the NUG is a bit different from the old NLD (National League for Democracy) led government. The NLD-led government was recommended by many of the groups because this is the only party-dominated government, and there are some ministers and deputy ministers, mainly from the NLD supporters and President appointed.

The CRPH decided to make a better, more diverse NUG. Inclusion is a big issue. People want to see that. There should be more diverse and multiple ethnic representation in the new government. This is the lesson we learned from the past. Myanmar is known as a very diverse country. By diverse, what I mean is that we have diversity of ethnicity, diversity of religion, and diversity of social status. If we learn from the past, we see one-party dominated politics without any active participation from ethnic parties. Hence, the CRPH decided to set up the new government with someone from the non-political, non-NLD parties. They also wanted to include representation from people with ethnic backgrounds, who are supported by ethnic people, women, and the Gen Z participation. During this spring revolution, many from Gen Z are at the forefront. So the leaders and young generation should be in the cabinet to represent them and to make good policy.

See, I am an openly gay person in the country, and I am part of the new NUG. This is great. This is a very diverse and multicultural government. This is the lesson we learned. And we are trying not to repeat the mistakes and take recommendations from civil society.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi would accept it, too, I think. I say this because she always said respect for diversity is the basis of human rights. The ethnic issue is very important, especially at a time like this, because the country is building a new federal democratic union. Without the ethnic representative or other diverse people in the government, it would be meaningless. This is in line with the guidance and statements Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has made before, so even though we have no direct communication or consultation with her, I believe that she would be happy.

The question is not that the new government has different ethnicities and the new generations involved. I think she might be more interested to know our future plan. What is our draft constitution going to look like? What is our new government going to look like?

For example, the ministry of human rights is the first of its kind in the history of Myanmar. Similarly, the federal affairs ministry is new too. So, I think she may personally be interested in our mission/vision and to know our plan. We need to explain and get her updated, but we are on the same mission and vision even if we don’t have direct communication. This government is an interim government during this revolution time, but we will make a better government when we have the space and more consultation with other leaders.

Kristina Eberbach: Thank you. You touched on this a little bit in terms of the importance of diversity and ensuring respect for minority rights, but could you speak about your mission and vision and what your priorities will be in this new position?

U Aung Myo Min: Ok, after I accepted this appointment, I’m thinking about what are my vision, mission, and strategies. This is a new ministry, and it is a cross-cutting one because a lot of the issues are interrelated.

The military is committing everyday violations across the country. Many people have been killed. Right now, about 800 people have been killed. People have been shot dead, including young children. Around 4000 people are in detention, many arrested without proper legal procedure. They are committing military offensives, including airstrikes in the ethnic minority areas. This has forced thousands of already civil-war-affected people. New waves of IDPs (internally displaced persons) have been created. Such incidents are taking place everywhere.

My background in human rights documentation came to my mind because it is important to collect all the human rights violations. I would say that not only are they committing human rights violations, but they are committing crimes against humanity. They are ordering systematically. Order and command are being passed out from the military to all the military, the police forces. This is taking place all over the country, not only in Yangon or Mandalay but everywhere! This kind of criminal act and various human rights violations should be well-documented and securely stored. There should be a strong database system so we can easily learn what is going on and the different trends and think about our next steps, as well as on the issue of accountability.

In Myanmar, we have long histories of the culture of impunity. We have more than five decades of civil war, and many people were arrested and detained, but the perpetrators were never taken to trial. The culture of impunity is so well-established that the survivors feel they have no protection and feel hopeless. They get used to it, but they think no one cares or will stop these things. On the other side, the perpetrators said, ok, we’ve got the license to kill, license to rape, because they don’t have to worry about any legal action against them. So, this is very dangerous, not only right now but for any future generation to face the culture of impunity. Stopping impunity and building justice is another step.

The judicial system in Myanmar has totally collapsed. No court is running properly. There are military tribunals where there is no legal protection or witnesses or testimonies allowed. So military officers just listen to the reports by the police and make a long sentence. It is hard for us to take legal action or exercise justice domestically. We need to beyond that. Regional countries and associations like ASEAN need to utilize their HR mechanisms to hold the perpetrators accountable. They can take some bilateral or regional intervention towards the military to start to bring the power back to the people.

Another issue is the international level. Myanmar is known as a long champion of violations of war crime against ethnic people and genocide against the Rohingya people. Now again, we have crimes against humanity. They are criminals. They should proceed and be treated according to the international criminal process. There are so many ways to do this. The UN can use the mechanisms of the human rights council. The security council can be pushed for responsibility/accountability for global/un-led intervention, but unfortunately, China and Russia are not supporting that one. Another way is the ICC, which already accepted the file of Myanmar for the genocide against the Rohingya people. Bangladesh is a signatory of the Rome statute, but not Myanmar. So, we are thinking, the NUG, as the legitimate government, can ratify the Rome statute.

This is all difficult and challenging. As I mentioned, the Human Rights Ministry is a cross-cutting ministry. Everything relating to Human Rights is our responsibility. For example, if we have the Ministry of Interior to propose the citizenship law under their mandate, but it is not only the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Ministry of Interior but also related to the Human Rights ministry. We have a long history of citizenship lawthath is discriminatory against minorities. For example, the people who are born in Thailand but live in Myanmar for a long time have no rights. So, we have to see this law from the perspective of human rights.

All the international human rights standards and considerations should be well-reflected, so I have to work with them. If we have another ministry, for example, the humanitarian affairs ministry, and if they decide to deliver humanitarian assistance along the border, then this is their job. But my ministry has to make sure no one is left behind. Everyone will need to be treated from a humanitarian perspective. There should be no discrimination and no abuse of power in food distribution or any kind of religious system. This is where my ministry is the focal ministry for every single ministry to ensure that every policy and program and action by ministers is in line with international standards. We have to check if this is not the right way and if there is something missing. For example, if the ministry of women, while drafting the violence against women law, exclude transgender woman, that’s not acceptable. I am doing this monitoring of every single policy, and you can see the responsibility for our ministry, just like the other ministries in the cabinet.

My background is from civil society. I duly respect the role of civil society, their commitments, their inputs, and ideas to make government better. That is what I had done when I was outside of the government. Government should listen to and coordinate with civil society. I have a series of consultations with different civil society members—by secretary, by ethnicity, by gender, you know, like women, and disabled, other minorities. Every day I have a series of

consultations to listen, and my duty is to make sure their recommendations and suggestions are well-reflected and implemented in the everyday policy of the government.

Ben Fleming: It is a very big portfolio, Myo. I don’t envy the number of meetings that you will have if we can switch gears quickly, in 1988, you went to the jungle to train, but you realized that your talents lie elsewhere. We now know that many young people are going to the jungles or taking up arms in their village. We know there was violence today in Mingyan, and in Chin State, the NUG has set up a People’s Defense Force and is negotiating with the EAOs [Ethnic Armed Organizations] in the hope that one day they can form a federal armed force. What are your thoughts on the process of defeating the junta? How would you speak to Gen Z? Is armed conflict a foregone conclusion, or can there still be a peaceful process, given the inequality of arms, what is it you hope for people to do?

U Aung Myo Min: Ok, you remind me of the days when I was a Gen Z back in 1988. I understand why many Gen Z have decided to leave for the border like me and want to take some kind of military action. There are two ways, the conventional military army and also the guerilla strategies. Young people think that we are left defenseless on the streets during the military crackdowns, and many are killed because they don’t have weapons to defend themselves. So they really want to fight back. They need weapons. I understand how they feel. Taking up arms is one of the strategies, but this isn’t the only solution to solve the problem.

We have so many other strategies and actions taken by different people every day at different stages. Some of the Gen Z are still out on the street every day. There is no massive peaceful demonstration like before, but there are still hit-and-run demonstrations. Youngsters are showing how they want their voices to be heard. They look for the flag. They are ready to join. They are showing the defiance of the people. The military has got the message that you cannot run the country like this.

First, that’s also opposition. Second, the civil disobedience movement (CDM), mainly by the staff, thousands of doctors, nurses, teachers, professors, and government servants, are still taking part in CDM. They are not going to work under the military government. There are huge numbers refusing to go even though the military is desperately saying everything is running well. We know that they cannot manage the situation while the massive CDM movement stays strong. This is another strategy. And this also is effective. You can see the military every day announces the list of people that got fired because they are part of the CDM. They threaten people who join the CDM. So, these are two strategies.

Third, the NUG is trying to work on the diplomatic strategy, using all kinds of international cooperation, trying to get the legitimate vote as the legitimate government. They are looking for international or bilateral cooperation for the NUG movement. This is also another strategy. That is why we are calling for intervention. We are asking ASEAN, EU, or the US government to take action on the military’s ‘three-cuts’ policies.

First, please cut the financial support to the military. Don’t do any economic transactions that benefit the military. Don’t do investments that directly benefit the military. Second, cut their weapons. For example, a small arm embargo can stop any kind of military training. It can stop any military-related support to the government. Third, cut the immunity to the military as a legitimate government. Bring these perpetrators to the stage of the international justice criminal system. With these three weapons and tools, we are working on our diplomatic strategy.

So maybe armed struggles and federal people’s defense forces are one of the strategies, but I would say it should be a combined strategy. Whatever path you take, our goal is to stop the human rights violations, abuses by the military, and step them down and bring in the normal civilian government.

Ben Fleming: To carry on from that, about the CDM. What are your thoughts on if and when the junta is defeated? What does national reconciliation look like? How do we reintegrate the Tatmadaw, in which case there needs to be a criminal process? But we are already getting so many messages from people who remain in CDM, those who have returned to work from the CDM, and also those who were never part of the CDM. We hear that these personal relationships have been broken, in some instances, beyond repair. How would you speak to those who remain in CDM, those who have left, and those who never were believed in the hopes of unifying the country and overcoming the junta?

U Aung Myo Min: How to deal with the CDM non-CDM and former CDM – good point! We have been discussing this issue.

For those who are committed to continuing CDM, the NUG is supporting them. Financially, at least with some international donations and through the overseas Burmese support, we are giving them the minimum amount. The money is not that much. But more so, we give them the recognition and moral support for their participation in the movement. But we cannot reach every single person who is part of the countrywide CDM. Communication is very difficult, and supporting CDM is considered a ‘crime’ by the military. We sometimes, we didn’t know the personal information of individuals, but at least we are providing some small token of appreciation to the CDM movement.

Second, we understand it has been 100 days already. Some people are having a hard time being in the CDM. Their whole family is kicked out of from the government. They have lost their quarters, jobs, salaries. They have to support their children and the elderly. We understand that one from a humanitarian perspective, humanitarian reason, and you know no one can be 100% committed, sacrificing their whole life. It happens, so we understand.

So long people are not being double agents, for example like informing on the other CDM people, and making reports, or forcing the other CDMs to return home, it’s fine. There are some people who are motivators for harassing the CDM movement staff. We are recording all these kinds of activities and making a list. The Ministries of Education and Health are also making a list. Such people might be expelled from the government jobs with the NUG side. We never encourage anyone to kill or abuse. We need to keep the dignity of the people even though they don’t have the same ideas or same side as us.

In the future, we can promise that we will compensate the CDM people who are still on strike to get their jobs back, get compensation and reparation, so we can make sure they are safe, that they can get their job back. We will give some kind of recognition to these people.

But for the people who are totally at the forefront of opposing the CDM movement, really, we cannot forget. There should be some kind of action. I don’t mean legal action, maybe not social action but some action by the government.

(Featured image courtesy of the Institute for the Study of Human Rights)

Like This Article