Michael Lidauer explores electoral politics in Myanmar.

The Tatmadaw sought to legitimise the 1 February 2021 coup d’état – which occurred hours before the newly elected parliament was about to convene – with one key narrative: that the November 2020 elections were marred by widespread fraud.[1] To counter this argument, twelve civil society organisations released a statement four days prior to the coup, declaring that “the elections were credible and reflected the will of the majority voters” (PACE 2021). Indeed, no evidence has become available that any electoral materials were tampered with.

The Tatmadaw has commented on weaknesses in the electoral process at several times before and even more so after the elections, referring inter alia to the question of organising elections under the conditions of Covid-19 and inconsistencies in the voter lists. Before the electoral campaign period, in August 2020, the Commander-in-Chief discussed with a delegation of political parties their concerns (The Irrawaddy, 15 August 2020). Although accepting the election results immediately after election day, the military fielded numerous objections regarding the elections and rejected the results during the weeks leading to the coup, and recapitulate this in their public communications (cf.[2]

Apart from the President, the State Counsellor and other governmental protagonists, the Union Election Commission (UEC) Chairman and members were arrested, and a new commission was appointed few days after the coup. In fact, the UEC became the single-most targeted institution with arrests and interrogations (AAPP 2021). Since then, the newly appointed UEC – headed by the same Chairman who was in charge of organising the 2010 elections – appears to build a body of evidence to substantiate the military’s claims of electoral fraud with publications about voter list data and ballots used in the 2020 elections in the Global New Light of Myanmar which yet await a closer analysis.

Given the unfolding dramatic events of civilian resistance, heavy-handed responses by the security apparatus, and the struggle for international recognition of legitimate actors, this appears of a lesser significance in the current situation. However, the underlying electoral narrative is likely to become reinvigorated if the Tatmadaw keeps to the idea of organising fresh elections, as announced in the Five-Point Road Map of the State Administration Council, coupled with proposals to change the electoral system.

This article seeks to look beyond claims of manipulation and provide more nuanced perspectives. While the elections have generated credible results, there were nevertheless a number of challenges related to long-standing weaknesses in the legal framework, political competition, and the dynamics generated by the Covid-19 pandemic, all of which are important to keep in mind for a more comprehensive understanding of the recent electoral process.

What is more, the organisation of elections reveals frictions in civil-military relations among Burmese elites from which ethnic minorities suffer as a consequence. As Myanmar people on all fronts oppose a new military regime and as the armed forces exercise their powers against the population, this article aims to recollect some elements of the electoral process preceding the coup, in the hopes of contributing to an understanding of the ongoing situation and of gathering lessons learned for times when elections in Myanmar will again be under scrutiny.

One such element is the cancellation of elections in parts of the country, a complex phenomenon that defies a simplistic explanation. Its analysis helps to understand majority-minority as well as civil-military relations even beyond the electoral process. Ahead of election day, on 8 November 2020, the polls were locally cancelled in many more locations than during previous elections, which resulted in disenfranchisement, political controversies, and diminished trust in the election administration (cf. ANFREL 2021: 45-51). However, while disenfranchisement was much debated, it was not a new phenomenon.

In Myanmar, electoral disenfranchisement pertains to multiple processes of exclusion from the ballot, affecting people in various ways. These systemic deficiencies have been part of the electoral legal framework since long and were no novelty to the 2020 elections. Disenfranchisement extends inter alia to voters who are not at their place of residence at the time of the elections but elsewhere in the country or abroad. This may concern the diaspora, refugees, migrant workers, students or other travellers, although procedures exist for those who are temporarily registered at a new place and could therefore “transfer” their ballot. Persons who are forcibly displaced by conflict (namely internally displaced persons, or IDPs) often cannot take part in the polls, as authorities repeatedly failed to develop and implement a consistent and effective policy for IDP inclusion at the ballot box.

Voting for IDPs was discussed ahead of the 2015 general elections, but was largely overlooked by national and international audiences, whose attention focused on the overall success of the election and its result, leading to a peaceful transition of power to a government led by the National League for Democracy. More debated – but not significantly tainting the perceptions of an overall well-run process at that time either – was the legal disenfranchisement of predominantly Muslim voters and candidates, preceding the mass exodus of the Rohingya to Bangladesh in 2017. The highly contentious Rakhine State politics during the last term ultimately altered how Myanmar was seen in the world.

The recently published article “Boundary Making in Myanmar’s Electoral Process: Where elections do not take place” discusses both the processes of “legal denial” for Muslim voters and candidates as well as the lack of voting opportunities for IDPs during the 2015 elections. It is part of the forthcoming Modern Asian Studies Special Issue on “Border Governance: Reframing Political Transition in Myanmar and Beyond”, edited by Kirsten McConnachie, Elaine Lynn-Ee Ho and Helene Kyed. The article also discusses election cancellations, which occurred ahead of the general elections in 2010 and 2015, but did not stir much controversy at that time. Despite affecting approximately half a million voters in 2015 – the phenomenon of election cancellations remained little understood. However, without further specifications in the legal framework and without transparent criteria for cancelling or postponing the polls, election cancellations occurred again in 2020, but this time attracted much more attention and controversial debates.

Myanmar’s legislation allows for localised election postponements due to risk of violence or natural disasters. While such decisions are usually informed by state institutions in the security sector and by election sub-commissions, the ultimate authority to cancel and postpone elections lies with the Union Election Commission.[3] The UEC is the constitutionally mandated body tasked with organising and overseeing elections. The UEC Chairperson and commissioners are appointed by the President. In addition to a permanent secretariat in Nay Pyi Taw, there are sub-commissions at state/region, district and township level. At the local level, the UEC relies strongly on personnel from other state institutions including from the General Administration Department (GAD) which until 2019 was under the authority of the military-led Ministry of Home Affairs (MoHA) and only then became part of the Ministry of the Union Government under civilian administration (cf. Lidauer and Saphy 2014; Renshaw and Lidauer forthcoming).

The cancellation or postponement of elections has different electoral consequences, depending on the size of the administrative unit concerned. Vacant seats in the legislature occur only where elections are cancelled for entire constituencies; in this case the need for by-elections arises. Conversely, the partial cancellation of elections in a number of wards or village tracts smaller than a constituency does not translate into vacant seats, but leads to the disenfranchisement of voters residing in the cancelled areas, as the election goes ahead regardless of their participation (Lidauer 2021). Vacant seats in the hluttaws at national level proportionally increase the voting powers of military representatives for whom 25 per cent of the seats are reserved.[4]

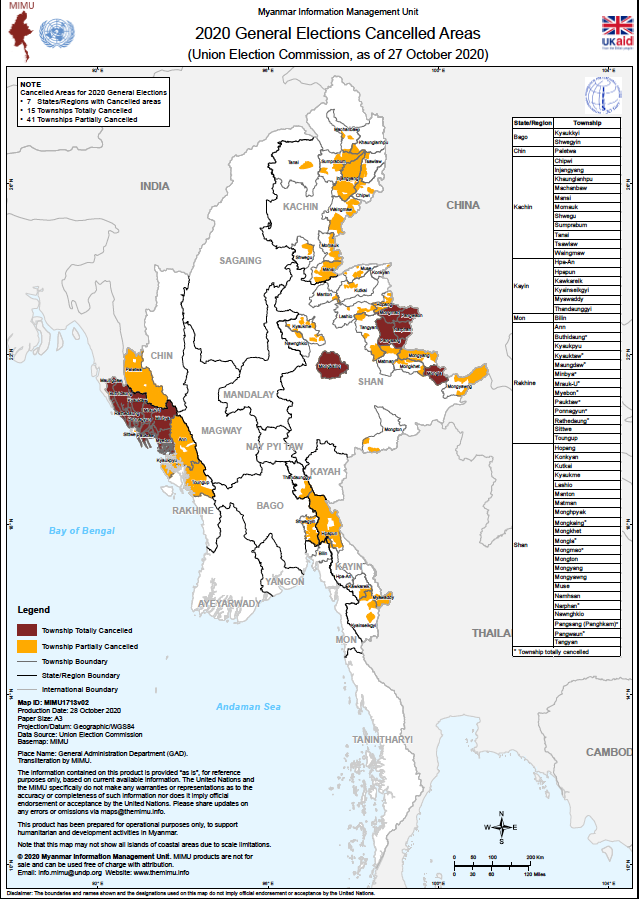

On 16 October, the UEC announced the cancellation of elections in a number of electoral constituencies where “free and fair elections cannot be held” (UEC Announcement 192/2020). While this timing and reasoning followed the pattern of similar announcements in 2015, the scale of these cancellations was unprecedented. Elections were cancelled for nine entire townships in Rakhine State and six entire townships in Shan State, as well as for 581 additional wards and village tracts in these States together with Kachin, Kayin and Mon States and Bago Region.[5]

The cancellations resulted in 15 vacant seats in the Pyithu Hluttaw (nine in Rakhine, six in Shan), seven vacant seats in the Amyotha Hluttaw (all Rakhine), as well as 32 vacant seats in states’ legislatures (20 in Rakhine, 12 in Shan). Based on data shared by the UEC, over 1.2 to 1.3 million voters did not have the opportunity to vote as a result of the cancellations, and 189 candidates (who had already started campaigning) lost the possibility to contest these elections.These decisions caused strong reactions among political parties and civil society organisations, with allegations of gerrymandering in Rakhine State. Several parties questioned the UEC’s impartiality in this process, demanded more transparency and consultations, called for ethnic voting rights to be protected, and for the decisions to be reconsidered. On 27 October, eleven days after the first announcement, the UEC made further cancellations public, notably for Paletwa township in Chin State[6] – raising the overall number of constituencies without elections to 54 – and revoked some of the earlier decisions. These additional announcements did not help to improve perceptions and trust in the UEC, but hardened the belief that its decisions would favour the incumbent.

The UEC decisions were criticised both for cancelling elections in some areas and for going ahead in others. In various areas, elections were in fact cancelled for different reasons, although on the same legal basis. The cancellation of four entire townships that form part of the Wa Self-administered Zone, and its ally in Mongla township – resulting in five vacant Pyithu Hluttaw seats and ten vacant State Hluttaw seats respectively – had been expected, as elections did also not take place there in 2010 and 2015. These are areas without any Myanmar governmental administration to prepare for elections, where a voter list had not been established, and no candidates had been enlisted.

The cancelled areas in Kachin State, Karen State and Eastern Bago Region (including one village tract of Mon State) followed a similar logic, as all these areas pertained to ceasefire areas under full or mixed control of ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) and have changed little since 2015, but did not result in vacant seats in any hluttaw. In Kachin State, elections were cancelled in fewer village tracts than in 2015 in a number of townships. In Kayin State, unlike in 2015, no elections were cancelled in Hlaingbwe township, and the cancelled areas were significantly reduced in Kyainseikgyi township. This was reportedly a result of negotiations between candidates and the election administration.

Partial election cancellations also occurred across Shan State. In southern Shan State, elections were cancelled entirely for Mongkaing township, where several EAOs are present. In northern Shan State, partial cancellations coincided with locations where armed conflict or tensions between the Tatmadaw, EAOs, and local militia had occurred. Kyaukme and Tangyan townships stood out with new cancelled areas while others were similar to 2015. In eastern Shan State, the cancelled areas corresponded to territories where the government has historically a weak presence.

In Rakhine State, where election cancellations were new, they were all argued for on the basis of security threats resulting from ongoing armed conflict between the Tatmadaw and the Arakan Army (AA). This included entire townships that ethnic parties and candidates considered safe, such as Pauktaw and Ponnagyun, and partial cancellations in other townships where only voters in small urban areas remained eligible to elect their respective representatives, such as in Taungup, Kyauk Phyu and Ann townships.[7] Widely held assumptions that all these cancellations would result in electoral outcomes favouring the NLD proved incorrect; in fact, ethnic parties secured the majority of elected seats in the Rakhine State Hluttaw despite the cancellations. The partial election cancellations in Paletwa township in Chin State, affecting a total of five electoral constituencies,[8] were also contentious.

The UEC’s decision-making process regarding the election cancellations became a public point of controversy at a high political level, involving the Office of the President and the Tatmadaw, and resulting in mutual accusations of shortcomings between the military and civilian leadership. The UEC stated that several governmental offices, including MoHA and the Ministry of Defence, were consulted to arrive at the decisions where elections should be postponed. The Tatmadaw, while maintaining that the UEC is the only authority to decide whether to hold elections or not, outlined that the UEC’s announcements did not reflect the military’s advice (Eleven, 20 October 2020).

In fact, this issue – touching upon civilian administrative authority but also upon questions of security, the Tatmadaw’s domain – was not the first point in time that saw military discontent with the electoral process, but brought tensions between the civilian government and the armed forces in particular to the fore. These discussions exacerbated ethnic parties’ frustrations about the exclusion of their voters from the elections.

In the immediate aftermath of the elections, the AA and Tatmadaw became unlikely allies in demanding that the cancelled polls should take place before the formation of the new hluttaws. In mid-December, this demand was supported by the President, and the Rakhine State sub-commission reportedly started preparations for by-elections (Radio Free Asia, 15 December 2020). For the AA, this was an opportunity to broaden their bargaining powers and increase their legitimacy. On the side of the Tatmadaw, the push for elections in Rakhine State was also interpreted as part of larger efforts to discredit the overall electoral process (The Irrawaddy, 20 January 2021). It was nevertheless unlikely that these elections would have taken place in the immediate aftermath, since, following amendments to the electoral laws in 2016 and 2019, by-elections for vacant seats cannot take place one year after and one year before general elections. In that context, by-elections seemed unlikely to happen before April-May 2022.

In the interim, the postponement of elections in Rakhine State appeared to generate an unexpected opportunity for a truce between the Tatmadaw and the AA (ICG, 23 December 2020); fighting ceased and tens of thousands were reportedly able to return home. In mid-January, the Rakhine State Hluttaw passed a proposal to urge the government to remove the “terrorist” designation of the AA. This designation, in place since March 2020, had been seen as an impediment to ceasefire negotiations. With an unusual expression of solidarity, Rakhine and Rohingya communities issued a joint declaration of mutual respect that emphasized not only elections for those areas where they were cancelled, but also for the Rohingya (Rohingya Today, 18 January 2021).

All interpretations about reasons for the cancellations and effects of vacant seats as well as speculations about early by-elections and any opportunities that may have come from this situation were overtaken by the coup d’état of 1 February. Portraying itself as the guardian of electoral democracy, the military leadership deployed a narrative of electoral fraud to justify its takeover. The public controversies around the election cancellations were one element in a longer process of discrediting the 2020 elections.

The issue of election cancellations demonstrates that the 2020 electoral process has seen a number of challenges, inter alia related to decision making process in the state administration. Although the final decision about election cancellations remains with the UEC, sub-national offices charged with informing these decisions were reporting within different hierarchies in the context of electoral security, turning decisions on localised election cancellations into an area of civil-military co-ownership and co-dependency. The process of election cancellations in 2020 illustrates the problematic nature of this co-ownership, which did not occur as such in 2015 when the leadership of the election management body had more direct communication channels with the security apparatus. As a consequence, the situation resulted in opportunities to criticize the UEC, despite the fact that similar cancellations had occurred in previous elections albeit at different scale.

The cancellations shed light on loopholes in the system – here, the lack of clear procedures for postponing the polls – that were present both in the 2015 and the 2020 elections, and show how weaknesses in the regulatory framework for elections amplified the opposition between the civilian and military parts of the State ahead of the coup d’état, with detrimental effects on ethnic minorities.

Now is not the time to strive for electoral reforms, but debates about elections and suffrage rights in Myanmar are essential and will eventually return. At that time, the transparency and process of any necessary election cancellations should be enhanced with clear communications and consistent criteria for such decisions, alongside other issues pertaining to electoral integrity, accountability and inclusion that will be important to address.

Michael Lidauer has been following elections and peace processes in Myanmar since 2010 as researcher and as advisor for international organisations.

References