A study by Nyan Corridor describes the military coup’s consequences for political parties and their future options.

Author’s note: This research was conducted by the Nyan Corridor, as part of the SEARBO project funded by the Australian National University. Interviews were conducted from May–August 2022 and data collection continued until 1 February 2023.

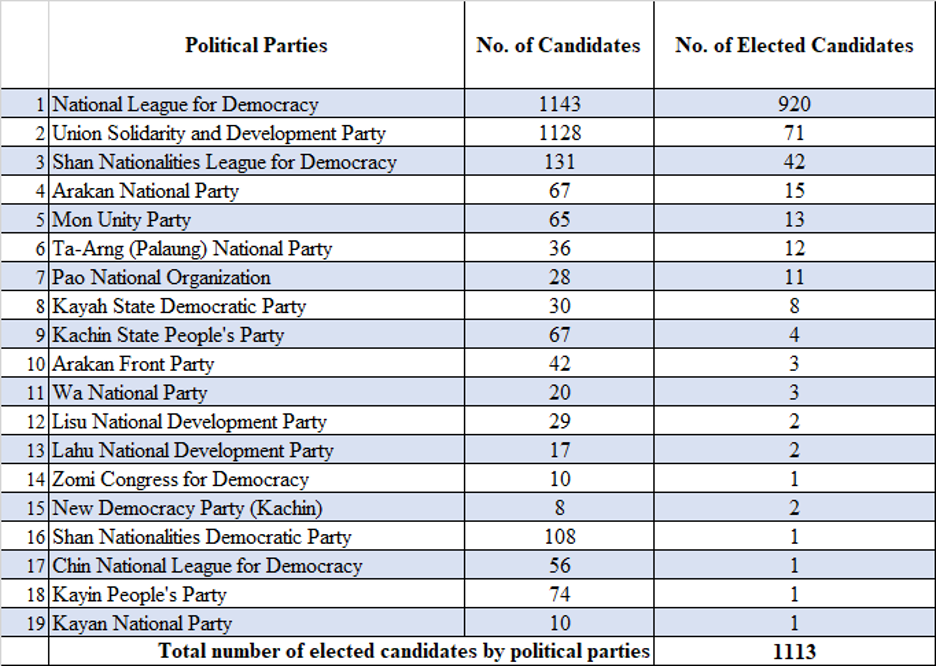

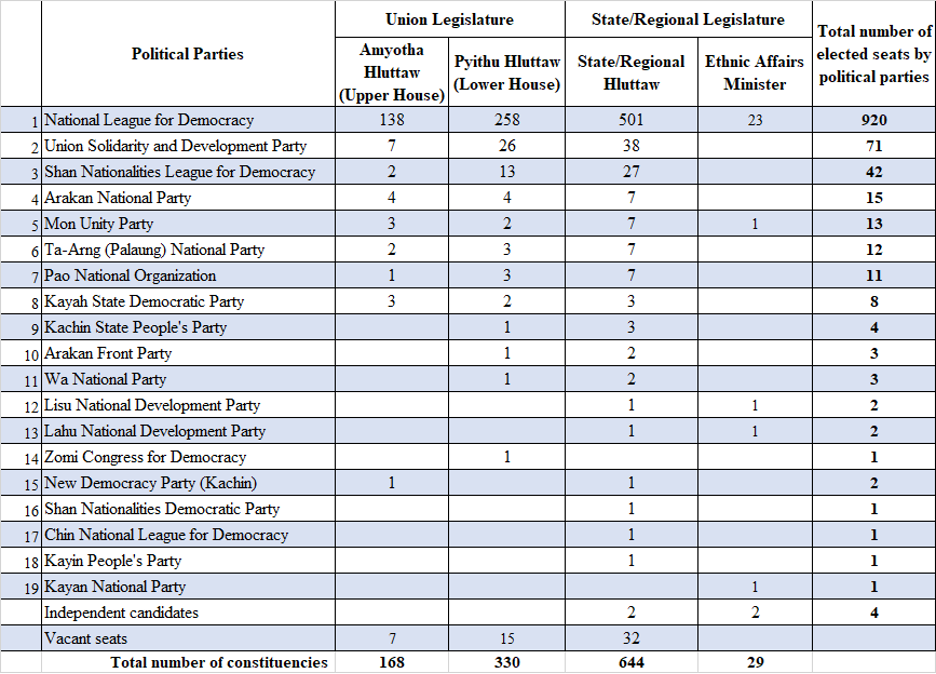

Myanmar’s attempted military coup illegally ended the country’s short-lived democratic period in 2021. This period had been haltingly initiated by regime reformists under the military’s 2008 Constitution, leading to comparatively free and fair elections that reflected the people’s will in 2012, 2015, 2017, and 2020. In the 2020 general elections, which were held during the immense challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, representatives from 19 political parties won seats in the bicameral legislature, the pyidaungsu hluttaw. Yet on 1 February 2021, the military junta prevented these new members of parliament (MPs) from forming a parliament and instead created the State Administration Council (SAC). This council was made up of military and representatives from seven political parties, and would go on to annul the 2020 election results and attempt to establish direct military rule through force. This led to many MPs, particularly those from the National League for Democracy (NLD), being detained, going into hiding, or fleeing the country. The junta then proposed another election be held under a new electoral system. If carried out, this election would be a potential watershed event, hindering the future of party politics and the institutionalization of democracy in Myanmar.

Since the 2021 coup, parties have either explicitly joined or at least aligned either with the SAC or with the alternative National Unity Government (NUG), which mostly consists of NLD members. Some prefer neither, being careful to maintain independence and claim neutrality. The SAC’s regular discussion of new elections has put Myanmar’s political parties, some more strongly incorporated than others after two years of weathering the effects of the coup, at a crossroads. Should these parties cooperate with the military-imposed and military-dominated performative parliament in order to gain limited power in a compromised system, or reject it entirely and work to institutionalize democracy through other means?

This research, conducted mainly through qualitative methods, addresses this quandary. To produce this analysis, our team first reviewed available party statements, media interviews, and news reports on party activities and electoral changes affecting parties. Thirteen political parties that released statements on the coup were then contacted for key informant interviews. Eleven of these parties participated in the interviews, along with a few former political party members, and all interviews were held between June and August 2022. In total, 25 party members were interviewed. Due to the sensitivity of the topic, some participants did not answer questions in detail, or answered only in a personal capacity and not as party representatives. For security reasons, many of the parties that participated in this study are not listed

When the military staged its attempted coup on 1 February 2021, it disregarded Myanmar’s nascent democratic institutions, most established under the military’s 2008 Constitution. These include the election body, the elected assembly, the elected government, and political parties, threatening their very existence. This was not the first time in Myanmar that the military staged a coup, abolished democratic institutions, and refused to transfer power to those elected by the people. In 1962, the military took control of the country and ended post-independence parliamentary democracy to supposedly prevent the break-up of the union.[1] The military annulled the 1990 election results and refused to transfer power to the NLD party and other winning ethnic parties, claiming they would draft a new constitution.[2] Three decades later, the 2020 election results were nullified by the army once again, with the military not only detaining incoming MPs but also the President, State Counsellor, and incumbent government, as well as members of the Union Election Commission (UEC), an ostensibly apolitical body charged with the management of the union’s electoral affairs. The military’s new SAC arbitrarily appointed a new UEC, led by the former UEC chair from 2008–2010, and tasked it with scrutinizing political parties and changing the electoral system from first-past-the-post to proportional representation (PR).

While many parties contested the 2020 elections, the major parties contending for a majority and national control were the NLD, led by Aung San Suu Kyi, and the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), a military proxy party mostly made up of former soldiers.[3] At the regional level, there was more competition with many local parties, the majority coalescing around ethnicity, challenging the two major parties. Nineteen out of a total of 91 political parties secured at least one seat in the bicameral and state legislatures. The NLD won even more seats than in the 2015 elections. The USDP and many smaller parties complained about the way the 2020 elections were conducted, pointing to new campaign regulations enforced by the UEC, which, when coupled with COVID-19 restrictions, advantaged the incumbent NLD party.[4] In August 2020, 34 of approximately 95 total registered political parties met with the Myanmar military commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing and requested that he step in and replace the NLD-appointed chair of the UEC on the grounds that the UEC was politically compromised and asked for the commander’s support if the election “turned unfair.” They also supported the convening of the National Defense and Security Council (NDSC), which many believed was a euphemism for a coup, as the military has no role to resolve electoral disputes under its own 2008 Constitution.[5]

Then, in September 2020, many political parties sent open letters to the UEC requesting the postponement of elections due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The USDP and its 23 allies stated that a meeting of the NDSC should be convened if the UEC did not proceed as required by the law, which meant holding the elections before 31 January.[6] The UEC decided to move forward with the elections on 8 November. After the elections were successfully held and the NLD won a supermajority of 920 seats, the USDP requested its supporters file complaints with evidence of electoral malpractices to challenge the results. At least 45 military-sponsored protests against the UEC and the election results were held in all the regions and states except Kayah, Chin, Rakhine and northern Shan states between the results announcement on 9 November 2020 and the coup on 1 February 2021. On 26 January 2021, the military claimed that there were 8.6 million discrepancies in the elections and said they could not rule out a coup if the UEC did not address these concerns, which were also forwarded to the UEC by more than 20 political parties. Less than a week later, the military attempted its coup, claiming electoral fraud and setting out a plan to appoint a new UEC which would scrutinize the supposed fraud and hold a new election, a move praised by pro-military parties. Many political parties were convinced by the military’s electoral fraud narrative, although it is widely considered to be false. Some claimed that the coup could have been avoided if the electoral disputes were addressed more transparently by the NLD-appointed UEC instead of ignored.[7]

Parties with their own grievances against the NLD did not immediately consider the coup as an existential attack on democracy against the wishes of the people and saw it instead as merely the next phase in a contest between elites. The military’s purge of the NLD and the cooperation of NLD-breakaway parties with the SAC—such as the New National Democracy Party, the National Democratic Force, and the People’s Pioneer Party (PPP)—did suggest that the military targeted the NLD with the coup rather than the system as a whole. The NLD leadership had alienated previous supporters in the lead-up to the 2020 elections by rejecting them as party candidates. There were 280 independent candidates in the 2020 elections; most ran as independents only because they were rejected from running for the NLD. After the coup, some NLD members reportedly signed a pledge to disengage from the party and the military claimed to offer political pensions to 217 former NLD MPs. On 21 September 2022, a group of people wearing NLD shirts (widely believed not to be actual NLD members) protested against the parallel NUG and the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), claiming the NLD does not support violent resistance. Recently, the NLD stated that a group of NLD members wanted to reopen NLD offices and negotiate with the military.[8]

The NLD also has only uneasy relations with the major ethnic parties who won seats in the 2020 elections. After the 2020 elections, the NLD sent open letters to 48 ethnic parties to discuss the formation of a coalition government named the National Unity Government.[9] Its negotiations with ethnic parties were halted when those involved could not agree on a meeting location. These uneasy relations are mostly due to events during the NLD’s period of incumbency: the NLD named an important bridge in Mon State the “General Aung San Bridge” (the military changed the bridge’s name again in 2021) and erected General Aung San statues in Karenni and Chin states. This was perceived as demonstrating Bamar majority thinking, ignoring protests from locals and aggrieving non-Bamar communities. The NLD also appointed all Chief Ministers in the country’s fourteen states and regions from their own party, instead of selecting from other parties which won a majority of seats in those state/regional parliaments. While this was in line with the 2008 Constitution, ethnic parties expressed discontent at what they saw as insensitivity from the NLD, and took these appointments as active steps by the supposedly pro-democracy party to prevent a more decentralized parliament.[10] The NLD also lost trust and broke alliances with parties that, together with the NLD, competed in the 1990 elections and then boycotted the 2010 military-run elections when it decided to contest the 2012 by-elections. These uneasy relations aside, the annulment of the entire 2020 election results by the new UEC surprised most political parties, particularly those who won seats and were expecting any new elections to be held only in disputed constituencies.

The CRPH was formed by 20 MPs, mostly NLD, who were elected in the 2020 elections, but managed to escape military detention following the coup.[11] This body later formed the NUG, claiming the people’s mandate. With the broad participation of strike committees, Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) members, ethnic armed revolutionary organizations, civil society groups, and political parties, the National Unity Consultative Council (NUCC) was also formed. These three institutions, the NUG, CRPH, and NUCC, make up a parallel government to provide alternative leadership to the people. The NUG abolished the 2008 Constitution and the CRPH drafted a Federal Democracy Charter with a roadmap for a future federal democratic union. The military and the NUG both declared each other an ‘illegitimate’ organization, and without resolving this problem, the military continued its plans for a new election, forcing political parties into an increasingly untenable quandary

Political parties in Myanmar have diverse origins and their political positions have always reflected this. Political parties were often categorized in two different ways by analysts during the period of 2010-2020. The first method splits them into three categories based on their priorities: pro-military, pro-democratic and pro-ethnic. Pro-military parties originated in the ruling parties from the pre-2010 authoritarian period and include the military’s associated proxy parties. Pro-democratic parties originated in the pro-democratic movement that struggled under military rule. Pro-ethnic parties originated from non-dominant ethnic groups to enhance ethnic interests and coalesce around ethnicity in elections.

A second categorization method splits parties into two groups, the “1990 parties” and the “2010 parties,” based on their contestations/boycotts of previous elections (and therefore their willingness to work within the military’s system). The “2010 parties” category refers to political parties that participated in the military-held elections in 2010. These were the first elections under the military’s 2008 Constitution and were widely seen as having been undemocratic. These elections were also seen as legitimating the military’s annulment of the 1990 election results and the twenty years of military rule and subjugation that followed. The “1990 parties” category refers to the political parties that boycotted the 2010 elections but competed in the 1990 elections, which are widely seen as having been democratic.

There were some mergers between pro-ethnic, 1990, and 2010 parties ahead of the 2020 general elections, pursued in order to increase their chances of electoral success and to form a stronger unified local party to better achieve ethnic equality and self-determination. These mergers created a stronger cleavage between pro-ethnic, on the one side, and pro-military and pro-democratic parties on the other. They also problematized the categorization of parties into separate 1990 and 2010 camps, given that some from each category merged together to form new parties. In the post-coup environment, where military rule and subjugation have been constant for over two years, a simpler and better method of differentiating political parties may be that of cooperation with the junta, resulting in a polarization of “cooperating parties” and “non-cooperating parties.” This cooperation has also impacted intra- and inter-party politics, particularly among the aforementioned newly merged parties. A loose alliance of five merged parties, which worked together before the 2020 elections, fell apart after the coup due to the parties’ different reactions to it. Further, one faction of party members in the Kachin State People’s Party (KSPP), who had all originally belonged to the Kachin Democratic Party, quit following the coup.

Only a few political parties have released public statements supporting or condemning the military coup. The rest either released neutral statements urging all stakeholders to resolve the issue in a peaceful manner, with no explicit statements either for or against the coup, or abstained from making any statements on the coup at all. Non-cooperating parties rejected the junta’s invitation to participate in the SAC and its state-level administrations, and have refused to attend meetings with the new UEC, participate in the Union Peace Dialogue Joint Committee’s (UPDJC) political parties block, or submit suggestions regarding the PR electoral system, among other forms of non-cooperation. The cooperating parties, on the other hand, participate in these opportunities, with some even taking up positions in the military administration. There are also cases where members from individual parties broke party unity and went off to join either the military administration or alternative political organs like the NUG, leaving their parties’ executives no choice but to expel them to ensure the party’s survival under military rule.

The rationale of non-cooperating parties is straightforward. They wish to fight against dictatorships of all kinds. Cooperating parties on the other hand are following their electoral and political objectives, often suffering from relatively limited capacities. Some parties prioritized their survival and the security of members when they decided to cooperate. The leaderships of most Myanmar political parties are dominated by older aged members with few young members, whose capacities for mobilization are limited. The chairperson of one party interviewed said, “we are too old to deal with the consequences if we go against the military’s ruling.”[12] A similar cost-benefit analysis was made by a party representative from a party based in an area surrounded by a river, who said, “Where shall we run if the military targets us?”[13] Other parties, particularly those who did not have any electoral support or who perceived no difference in advancing their political objectives, prioritized the immediate benefits of complying with and participating in the military administration, while also reducing their risk of being targeted. One party individual explained this view with the metaphor “chilies are spicy whether green or red,”[14] with the green referring to the USDP/military and the red referring to the NLD.

Because formal and informal relations between 1990, 2010, pro-ethnic, and pro-democracy parties in the post-coup period are much more common than before, and the nature of party politics has changed, cooperation with the junta is now the key differentiator and best way to describe and analyze parties and their actions.

The minimal expected role of political parties in institutionalizing democracy is to engage with their constituencies, organize party activities, develop policies over issues concerning their electorate, represent their electorate, compete for office, and be accountable for their policies. Many parties claim there has been no change in their policies or party platforms since the coup, particularly due to their inability to convene a party conference to make such changes. Political parties have been unable to resume these and other regular party activities, which were already long-prevented by COVID-19 restrictions. Since the start of the pandemic, internal party meetings were mostly online. One party representative said, “The closest thing we could do as a party was approving a new township chair when the old one resigned.” Even that was done through online communications.[15] Only cooperating parties with connections to the military’s administration in Nay Pyi Taw have been able to carry out party activities such as opening new branches.[16]

After the coup, members disengaged from their parties, often because they did not necessarily agree with their party’s leadership or simply for security reasons. Many members resigned in silent protest from political parties that chose to cooperate with the junta after the coup. While the number of party members that deserted varies by party, the total effect posed enough of a concern to encourage parties to question their internal decision-making processes. For example, one-third of the Central Executive Committee of the Mon Unity Party (MUP) resigned from their positions. One MUP individual said, “The party (MUP) is not in line with policies fighting against dictatorship.” Being a party recently reorganized through a merger, which still had enduring intraparty factions based on previous affiliations, desertions could lead to the formation of a new rival party and divide the MUP’s supporters, something which does not seem to faze the MUP leadership based on our interviews.[17] Non-cooperating parties on the other hand stayed low profile, with a couple of them transforming into underground parties in order to participate in the anti-coup resistance movement.

All the parties interviewed, both cooperating and non-cooperating, said they had not formally engaged the public since the coup. Party movements were impacted by armed conflict, inflation, reduced trade, and movement restrictions in different states and regions. Although some party members have actively helped the public with education, health, food provisions, and legal advice, these activities were not carried out under the name of the party. One party member interviewed said, “We cannot act as parties as this is very sensitive at the moment.”[18] The cooperating parties, who took more liberty in organizing party activities, have been able to hold internal party meetings in townships without active anti-coup armed resistance. But they could not extend their engagement to wider public meetings nor gather to hear public opinion. One cooperating party member said, “It would be a lie to say we talk to the public and know what they think.”[19]

Only two political parties, the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy Party and the MUP, have been able to organize a party conference since the coup. The former claimed holding their conference was to push for civilian participation in politics in an increased militarized context. The latter claimed the conference was overdue and required by party rules.[20] Meanwhile, many political parties tried to stay relevant to the changing context by releasing statements, expressing their views, and engaging with interparty platforms. Cooperating parties used meetings with the UEC and the UPDJC as channels for communicating with other parties. Non-cooperating parties and entities gathered under alliance platforms for analysis and strategizing, such as the People’s Representative Committee for Federalism, which mostly involves members of the United Nationalities Alliance (an alliance of 1990 parties). However, there is no viable crossover or independent platform for multi-party dialogue across the dividing line between cooperating and non-cooperating parties. A party representative from a cooperating party stressed the absence of such platforms, saying “We are not invited to NGO-led party dialogues like in the past. I don’t know if they are happening or if they are boycotting us.”

Based on our interviews, two years after the coup, members from both cooperating and non-cooperating parties have not yet achieved their fundamental goals regarding the country’s constitution. Some cooperating parties are pushing for constitutional reform, demanding the amendment of Article 261 of the 2008 Constitution (the law stipulating the appointment of chief ministers) for greater self-autonomy and the addition of a clause setting a percentage of seats and time limit for the military’s withdrawal from parliamentary politics. Neither has been agreed to by the military. Other more immediate goals of these parties have also not been granted despite their cooperation with the junta. For example, the Arakan National Party (ANP) demanded the chair position of the Rakhine State administration, to reflect the fact that it won the majority of votes in the 2020 elections, but this was denied.[21] The MUP requested the junta recognize Mon National Day as a national holiday, but this was also ignored, despite the MUPs direct participation in the national military administration.[22] The Kayin People’s Party submitted suggestions on the new PR electoral system for a two-day PR conference on 5-6 November 2021, but they were ignored.

Non-cooperating parties favor rewriting a new constitution with federal stipulations to replace the undemocratic 2008 Constitution. However, they have not been able to unite and finalize a new federal constitution accommodating diverse interests and accepted by other federal democratic forces. They have also failed to create a platform for non-cooperating parties to dialogue with one another. Federal- and state/region-level constitutions have been drafted by multiple groups, including cooperating and non-cooperating parties, but both party types draft their constitutions unilaterally with no or minimal coordination with others. Currently, parties see no way to unify on constitutional issues. They cannot reach their fundamental goals despite cooperating or not cooperating with the junta.

Two years after the coup, politics has become only more unstable in Myanmar. The military persecutes those who defy its rule and continues to target democracy and human rights activists, journalists, CDM participants, party members, and opposing party supporters. Many are killed in interrogation before reaching courts or prison. Those who survive are sentenced with political charges set by the military and police and parroted by a compromised judiciary. The military has extended its recruitment of village administrators and party members into its ranks, or co-opted them as proxy forces, providing military training and equipping them with arms to take control at the local level. They have also continued calling back retired veterans to directly serve. The NLD reported on 5 January 2023 that 1,232 of its members have been arrested since the coup, that 84 members and two MPs have died in military detention and 577 houses belonging to NLD MPs and members have been illegally confiscated by the military. Party members and party supporters have also been searched for and killed by military proxy militias such as Pyu Saw Htee and pro-military vigilantes such as Thway Thauk Group.

Anti-coup resistance groups have used violent and non-violent means to counter the military’s severe crackdowns. People’s Defense Forces were formed, some independent and some under the command of the NUG, and have attacked military and civilian targets, including those involved in the military administration, military informants, and Pyu Saw Htee members. Also persecuted by military troops on the ground, the USDP claimed on 26 March 2022 that its members had been killed, forcing some of them to move to Nay Pyi Taw for security and protection.[23] The conflict has spread in the last two years. In 2021, there was a 620 percent increase in conflict incidents driven by the military’s violence against civilians compared to 2020, and a 32 percent increase in such events recorded in 2022 compared to 2021, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. At least 310 of 330 total townships have experienced conflict and violence including targeted and remote attacks, pitched battles, and airstrikes. Some townships have had their military administration operations severely challenged by anti-coup resistance groups. On 5 September 2022, the Special Advisory Council to Myanmar reported that the military has direct stable control over 22 percent (72) of Myanmar’s total townships, but this number increases into the 100s if those held by military proxy militias are included.

Against this backdrop, the military has been planning to hold its new elections using the ‘List’ PR system. Its administration has redrawn administrative districts, creating a total of 116 districts, but has not commented on whether this will affect the makeup of the existing electoral districts. Meanwhile, 1.5 million people have been internally displaced nationwide since the coup, while others have willingly migrated, impacting the composition of electorates. The new military-appointed UEC ordered parties to seek approval before meeting with international organizations, limiting their freedom.[24] The UEC also warned the ANP on 12 October 2022 not to release “one-sided statements” after the party condemned the military’s 25 September airstrikes against civilians and its 25 July executions of four democracy activists, including 88-generation leader Ko Jimmy and former NLD MP Ko Phyo Zeya Thaw.[25]

The anti-elections campaigns of resistance groups also continue to disrupt the military and cooperating parties’ interests in planning the election. Strike groups campaigned for the public to boycott the military’s illegitimate elections and sent advocacy messages to the international community. On 14 June 2022, the NUG also called for the people to put an end to the regime’s fraudulent elections. In recent months, resistance groups have targeted local administrators involved in collecting population lists to prepare a voters list and have shot at, bombed, and set local administration offices on fire. Cooperating party members are reportedly scared to participate in the elections. Military-administrated elections may not be held on a large scale or even simultaneously, focusing instead on the electoral districts the military controls and where they can manipulate the results. Analysts warn that such staged elections would only increase violence in the country.

Two years of military subjugation has left most political parties with nothing but dismay. Parties are at the crossroads of either integrating with a military-imposed, performative political system or working to genuinely institutionalize democracy through an alternative system that could shape a different future for Myanmar. Both the cooperating and non-cooperating parties interviewed said they do not believe elections are the solution to the current political crisis, and that they would not be inclusive, stable, legitimate, or peaceful, given the political instability in many parts of the country. However, being influenced by reformist thinking, most cooperating parties said they would participate in the elections, at least in order to maintain the status quo, if not to push for change from within. Political party members recalled the past in their interviews when they could mobilize, be elected, and represent their constituents at the people’s assembly peacefully—and in the presence of military MPs also in the parliament.

Under the 2008 Constitution, 25 percent of parliament’s composition was reserved for military members. They had a fixed 110 seats for 330 elected seats in the lower house and 56 seats for 168 seats in the upper house, making a total of 166 reserved seats to 498 elected seats in the parliament. Showing symptoms of potential ‘Stockholm Syndrome’, one party member even said he “would accept (a situation where) civilians and military (representation in parliament) was 50–50, as long as there is at least some civilian control.”[26] Another party member thought it would be too risky to let the military have 100 percent control. He said, “we should use every means to make sure the military does not hold absolute power alone.”

Based on our interviews, some political parties also see an increased chance of success in a military-led election without the NLD. Local parties received the second-highest votes after the NLD in the 2020 elections in their relevant states, but in Shan and Rakhine states, the SNLD and the ANP won the most votes outright. Here the polarization between 2010 and 1990 parties is useful once more: 2010 parties see an increase in their electoral success in the absence of their 1990 counterparts. For instance, the Shan Nationalities Development Party (SNDP) won the majority in the Shan State parliament in 2010, with 36 seats, and received 22 seats in parliament. When the SNLD rejoined the electoral contest in 2015, the SNDP won only one seat in Shan State and received no seats at the national level. The composition of parliament during the USDP term from 2011-2016 forms something of a template of the results expected by parties expressing interest in contesting a new military-run election. Needless to say, political parties who are already benefiting by aligning with the military aim to perpetuate that benefit by entering any planned elections.

Ongoing armed resistance is also pushing some political parties to opt for the electoral route. Political parties feel threatened by increased militarization and shrinking public space following the coup. Some party members disclosed that participating in the elections may help parties claw back more space for civilian participation in politics and therefore speed up gradual reform. Political parties with leaders who were involved in armed resistance in the past, and/or who were imprisoned, and saw no clear political progress for decades, are in particular convinced that compromise is the only option. Members of these parties claim political parties are exclusively above-ground organizations that must work to achieve political objectives through non-violent means. Some political parties also face an existential dilemma. They are convinced that the 2008 Constitution will be dissolved unless elections can be held and a transfer of power does not take place after the expiry of the two six-month extensions of the one-year state of emergency announced when the military took control.[27] One interviewee remarked, “It took 18 years to draft the 2008 Constitution. How long would it take to draft another?” Apparently, it is not a technical but a political problem for parties. Another interviewee said, “We only need to decide whether to enter the elections or not, not under which electoral system.” On the other hand, parties will be deregistered by the SAC if they do not participate in the military’s elections and may face security challenges as a consequence.

The question arises, “What is the alternative to an election under the military-imposed system?” After two years, it seems the parallel government and non-cooperating parties have failed to develop a strategy to provide such an alternative or achieve their goals. Recently, the NLD and the SNLD both separately called for “all democratic forces” to unite, but they did not reveal what to unite for, or how, with no clear policy for the role of political parties. The NUCC’s previously mentioned Federal Democracy Charter uses vague language, referring to political parties as “allied political parties” and “political parties which agree with the federal democracy charter” and features no policy for pro-military parties, cooperating and non-cooperating parties. Technically, only one party—the Democratic Party for New Society (DPNS)—participates in the NUCC political parties’ group. The NLD suspended its participation in the NUCC after its first People’s Assembly when the NLD research department released an internal paper claiming the NUCC lacks legitimacy. While part one of the Federal Democracy Charter was reportedly created with reference to interim constitutional documents drafted in 1990 by NLD lawmakers and ethnic armed forces and accepted widely by federal democratic forces including ethnic revolutionary organizations, part two, drafted in 2021 and criticized for keeping some features of the 2008 Constitution, was more problematic and led to distrust between non-cooperating parties.

To create a new system, the parallel government needs to incorporate a cost-benefit analysis for political parties in general and offer them a genuine alternative strategy with inducements. Non-cooperating parties require a political consensus with other federal democratic forces including the NUG, CRPH, and NUCC, that is respected, entrusted, and committed to by leaders and their followers, to be able to work together towards a common goal. Having the Federal Democracy Charter is one thing, working on the emergence of a federal constitution that accommodates diverse interests is another. One party member interviewed said that “The Panglong Agreement would be a good starting point” from which to work together among those who want to create a federal democratic system. This process would require not only dialogue but also trust building. The challenge for political parties would be asserting their roles while working with and for their counterparts and supporters.

If political parties do not want to opt for either a military-imposed system or another one offered up to them, the next question arises: What other options do political parties have? There is no viable third-party force at the time of writing. All political party members interviewed believed that negotiation is the answer to resolve the current political crisis, or at least they believed all sorts of conflicts will only ultimately end at the negotiation table. Yet, they did not share similar views on who should be involved in these negotiations or on which conditions the negotiations should take place; none revealed their ideal conditions for negotiations. One NLD leader said minimum terms include the immediate withdrawal of the military from politics and a public apology from the coup leader and the military to the people, amongst others. As most NLD leaders, including the party chair, were arrested, whether this view is party policy or widely agreed upon within the party could not be confirmed.

Most political party members interviewed said a third power or mediator is needed for negotiations—either internal or external to the country. Many believe the participation of NLD de-facto leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is the key to negotiation while others thought major power countries could successfully facilitate negotiations. Some members from cooperating parties said that they promoted negotiation when they talked to international stakeholders—at least until their meetings were blocked by the military-appointed UEC. While cooperating and non-cooperating parties share a preference for “negotiation,” they have different terms in mind and hold no real power to be brokers themselves. One party representative interviewed provided an example of political paradox, mentioning a time when a Karen National Union statement said they would join talks for peace only if the military leaves politics, and the military stated that they would only leave politics when there was peace.[28]

History has shown how difficult it is for political parties to unite and become a third power in Myanmar’s national politics. Political parties who do not believe in doing so at all simply focus on their ultimate goals. Some party members interviewed declared they would never participate in the military-organized elections. One party representative said they “will sacrifice their party” for the greater cause. One stated confidently, “As long as there are party supporters, the party will live on”, a sentiment similar to that of the NLD party. The 2021 anti-coup democracy movement also brought opportunities in disguise for parties to reconnect with society organizations, interest groups, and mass movements, as legitimacy is the most important thing to achieving long-term electoral and popular support. The NLD is one mass party that enjoyed popular support since it was born in the 1988 uprising, winning a majority in three national elections—1990, 2015, and 2020. Political parties now also have the opportunity to refine their policy positions as the early days of the anti-coup resistance movement revealed popular support for gender, human rights, and governance reforms, including a new form of federalist democracy.

Stronger political participation in the pro-democracy and anti-coup movements could also mean people have less faith in the current political parties, posing a challenge for institutionalizing democracy, on the other hand. Party activists could invest in the younger generations to participate in party politics, as political parties hold a legitimate mandate to aggregate and represent public needs, transform them into policies—and then be accountable for the consequences of their policies. The younger generations could carry on the legacy and policies of older political parties. The DPNS seems to be following this path with party reform and incorporation of its youth wing, which engages in social democracy movements and the party’s affairs.

Parties favoring the drafting of a new federal constitution strongly object to the military elections as they would not only delegitimize the pro-democracy and anti-coup resistance groups but also legitimize the military’s role in politics. Despite all the concerns given by cooperating parties above, parties with “push within the system” thinking will only reinforce the military’s domination of politics with no guarantee that they will have any influence on the system; this is prioritizing immediate gratification over long-term advantage. The past has shown that such thinking is actually a cause of the endurance of the military quota in parliaments. Political parties only think about whether the military will dominate parliament if the electoral system is changed, rather than whether the change will increase the participation of minorities and women. Competition and tensions between political parties have been affected by the fact they compete in a parliamentary system affected by a guaranteed military quota. This was shown in the 2020 electoral campaign messaging. Even for the amendment of article 261 of the constitution, relating to the appointment of regional ministers, many political parties have been hesitant to push for it, even though they may prefer it in theory, due to their concern that the military would have influence over the appointment process, given their quota. Because of the military quota, parties cannot effectively prioritize increased decentralization and a more robust federation.

The military coup made all the votes cast in the 2020 elections obsolete and forced parties to react to the power grab, weakening the institutionalization of party politics in a future democratic Myanmar. Parties have divided on the issue of whether to contest the military junta’s elections or not. The coup scrambled intra-party politics, with a disproportionate impact on recently merging parties. It also reshaped inter-party politics as parties realigned their positions and reformed their alliances. Although many parties, both underground and above-ground, stayed relevant in the changing context, their institutional roles disappeared with the coup. The coup disabled political parties’ abilities to engage with communities, perform party functions, represent people’s interests, and translate them into policies and laws. Neither cooperating nor non-cooperating parties have achieved their immediate goals or been able to meaningfully participate in post-coup military politics.

While political parties believe negotiation is the only way out of the political crisis, they have no real power and cannot exert pressure to bring the Myanmar military and anti-coup resistance forces to the negotiation table. In the absence of alternative strategies, most political parties are inclined to contest the military’s elections for survival or for presumed political benefits. Political parties are in a quandary: Should they reinforce the military-imposed system by contesting the elections? Or should they unite with other resistance forces and push for a federal democratic system that respects equal rights? Or should they build a third force large enough to bring all concerned entities to negotiation? Or should they defend democracy by engaging in party activism and connecting with the mass movement? Whichever way they go, political parties will be answerable for the consequences of their actions and the system they help create or maintain. Political parties that decide they know what is best for their electorate, rather than representing their electorate’s decisions in parliament, will be accountable for the consequences of that choice.

Coda: On 26 January 2023, the military-appointed UEC issued the Political Parties Registration law which posed stricter registration requirements. Political parties registering at the national level as a Union party must organize at least 100,000 members within 90 days and open party offices in at least half of the townships across the country (330) within 180 days of the date of approval. Political parties registering at the state and regional level as a state party must organize at least 1,000 members within 90 days and open party offices in at least five townships of the concerned state or region from the date of approval. Union parties must deposit 100 million kyat and state parties must deposit 10 million kyat at the state-owned Myanmar Economic Bank. On 29 March, the UEC announced that 40 parties including the NLD were dissolved for failing to re-register within 60 days as stipulated in the Political Parties Registration Law, article 25. In the same announcement, the UEC stated that 63 political parties were re-registered, with some using the same name and others using new names.

Nyan Corridor is an independent non-profit research institution working to support Myanmar scholars and the revitalization of an independent research culture in Myanmar.

Notes

[1] The Hanthawaddy Weekly Review, March 1962. Cited in “၁၉၅၈ – ၁၉၆၂ မြန်မာ့နိုင်ငံရေး စတုတ္ထတွဲ” (1958 -1962 Myanmar Politics, Part IV), published by University Press Yangon in 1991.

[2] U Kyi Myint, February 2021. “ရှစ်လေးလုံးအရေးတော်ပုံကြီးနှင့် ယနေ့မြန်မာ့နိုင်ငံရေး “(Four Eights Uprising and Today’s Myanmar Politics).

[3] In the 2020 elections, the NLD fielded the largest number of candidates (1,143), followed by the United Democratic Party (UDP) with 1,130, and the USDP with 1,128. The UDP was dissolved by the Union Election Commission in mid-October 2020, making the USDP second largest competitor.

[4] These reports were repeated in personal interviews with the author during the 2020 pre-election period.

[5] The NDSC is made up of eleven members, with the military holding six seats in the council. The NLD administration avoided convening any NDSC meetings during its term, despite multiple calls by the military, USDP and their allies for meetings to discuss major national issues such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

[6] Under the military’s 2008 Constitution, elections are to be held every five years. The previous parliamentary term (2016 – 2021) was convened on 1 February 2016.

[7] The first incident to occur after the election is that there was over a gap of one million voters between the data in the state media published on 10 November (n=37,268,876) and the UEC data released on 30 November (n=38,271,447). Parties and analysts criticized the UEC’s non-transparent explanation of the errors.

[8] Personal communication.

[9] This vision of forming NUG right after the NLD victory was different to the current NUG in terms of the order of the governance system. The former is based on the NLD policy which favored democracy over federalism, referring to ‘a democratic federal union’ and the latter is based on ethnic groups’ preferences which prioritized federalism over democracy, referring to ‘a federal democratic union’.

[10] Article 261 of the Constitution allows the president to appoint state/regional chief ministers. The Arakan National Party won the majority of seats in the Rakhine State parliament in 2010, but the chief minister was appointed by the USDP. The same happened in 2015. Despite the ANP winning a majority in the state, the NLD appointed its own Rakhine State chief minister.

[11] On 5 February 2021, the CRPH was formed with 15 NLD MPs, later extended to 20 with MPs from three different parties. The NLD party’s D-Wave journal wrote that 298 members of the bicameral legislature attended an online conference convening the first parliamentary session and forming the CRPH.

[12] Personal communication.

[13] Personal communication.

[14] Personal communication.

[15] Personal communication.

[16] According to the Burma Affairs and Conflict Study, four political parties—the USDP, National Union Party, PPP, and PP—have had the most party activities such as organizing, internal meetings, voter education, putting up party signboards, and meeting with other parties and foreign organizations.

[17] It was reported that about 500 party members deserted the PPP and only its four top leaders are operating the party.

[18] Personal communication.

[19] Personal communication.

[20] The USDP organized a party conference in August 2022 and the KSPP organized a party conference in January 2023, but this was not included in this study.

[21] Personal communication.

[22] Personal communication.

[23] The USDP made unlikely claim that 1,327 of its members were killed, a number comparable with the number of civilians killed in the anti-coup resistance movements over the same period. According to the AAPP, a total of 1,707 civilians were killed in anti-coup movements by March 25.

[24] The UEC recently released the political parties registration law, further limiting the participation of political parties in the election in terms of finances and membership. It also limited the involvement of the NLD.

[25] Only 18 parties released a statement on the executions of the democracy activists.

[26] Personal communication.

[27] The military extended the state of emergency for another six months, announced on 1 February 2023 and consequently delayed the proposed elections.

[28] Personal communication.

Like This Article

December 18, 2024

April 09, 2024

March 20, 2024

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023