Jae Park and Alexandre Pelletier call attention to gender in thinking about conflict in Myanmar.

Despite the signing of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement in 2015, Myanmar is still at war with itself as fighting in Kachin, Rakhine and Shan states shows no sign of ending. The loss of human life, as well as the material destruction and shattering of local communities caused by the 70-year-long conflict, continues to incur heavy social and economic costs in the country.

While war affects all, it affects men and women differently. In any conflict setting, gender creates expectations and exposes individuals to different dangers and vulnerabilities. In Myanmar’s conflict areas, many boys and men have had first-hand experience of violence as soldiers and live with its physical and psychological consequences. In these regions as well, many girls and women face an acute danger of gender-based violence as their bodies are objectified for war purposes and human trafficking.

The different impacts of war on women and men have to be taken seriously to move the peace process forward and to design policies that address the long-lasting consequences of war. In Myanmar as elsewhere, decentralization is considered as a democratization tool, a means to achieving better government accountability in the delivery of public services and a gateway to women’s participation. The conflict and its political and economic legacies not only perpetuate, but may also reinforce gender practices, inequalities, and discrimination. If gender needs and inequalities are not addressed, the very success of democracy, the peace process, and decentralization in Myanmar will remain unequal for men and women.

In this piece, we bring together evidence from local communities to examine some of the impact of conflict on male and female populations. We collected evidence for this paper in 2018 and 2019 as part of an International Development Research Centre-funded project—a collaborative project between the University of Toronto and the Myanmar Institute for Peace and Security. The research team interviewed local stakeholders such as women’s organizations, ethnic armed organizations, politicians, and government officials. It also conducted a survey of 2,747 household heads in Chin, Kachin, Karen, and Magwe (hereafter referred as the UofT-IDRC survey). This paper is not an exhaustive list of the impacts of conflict on gender, but highlights some of the themes that emerged frequently during our work.

Civil wars have significant impacts on both men and women. But boys and men often have a particularly direct, first-hand experience of conflict and violence through their experience as soldiers. Many of them have volunteered to join Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAO) out of loyalty to their ethno-national group and because of feelings of injustice and grievances against the government and the Tatmadaw. But mixed with these motivations are also gendered expectations about the proper behavior for men. Many communities and families expect men to assume the role of “protectors” of the community. In time of crisis, this expectation is only strengthened, which factors heavily in the decision of boys and men to join EAOs. In many communities, there is no stigma in joining an EAO, but boys feel a sense of responsibility toward the community and see their involvement in military activities as a source of respect.

In northeastern Myanmar, where conflict has recently escalated, EAOs are also known to have, at times, conscripted young men to bolster their ranks. Whether local populations see conscription favorably varies from one EAO (and one region) to the other. The RCSS, TNLA, and KIO have similar recruitment practices and expect, in general, at least one abled man over 18 years old by households to join the groups’ ranks. Most EAOs claim to discourage forced recruitment, but as Amnesty International puts it, “the line between forced and voluntary conscription is at times blurred by the sense among some families that it is their duty […] to ‘serve’ in an ethnic armed group” (p. 40). Some perceive conscription as forced recruitment, however. It seems to be particularly the case when recruitment takes place across ethnic groups, which has happened in both Kachin and northern Shan state. To escape the draft, families have paid bribes, while others have married their son earlier, fled from their community or even forged their own funerals. Some local communities, with the support of the Tatmadaw, have even formed militia groups to retaliate against EAOs. Villagers, boys and men in particular, have become entrapped in this militarization of their own communities, which make the return to normal life after the conflict more difficult.

Boys and men also experience conflict first-hand by being forcefully recruited by the Tatmadaw. In its operations, the Tatmadaw has forced villagers to act as porters, laborers and, worst, “human shields” and “human mine sweepers.” To force civilians into compliance, the Tatmadaw has physically threatened and forcefully taxed, detained, tortured, or killed uncooperative civilians. While the Tatmadaw has targeted both men and women, men are particularly likely to be drafted for physical tasks, exposed directly to hardship and violence. Recruitment drives in Shan State, for example, have left numerous villages with few men, breaking families apart and threatening social cohesion. When the Tatmadaw do not forcefully recruit men, it often targets, question and arrest them while traveling for their suspected ties to EAOs.

Communities and families also expect men to act as providers in addition to protectors. In conflict-affected areas, however, insecurities as well as numerous checkpoints, curfews and landmines laid by EAOs and the Tatmadaw seriously constrain movements. In these contexts, options for education and livelihood are extremely limited. Some men are forced to migrate for work, while others have joined EAOs or the Tatmadaw out of exasperation.

Those who find refuge in Internally Displaced People (IDP) camps do not fare better. These families have recently loss access to their land, exhausted their coping mechanism, and are newly poor and unemployed. While poverty affects all, due to social and gender expectations, men often feel psychological and socially distressed when they are unable to provide for their families. Some suggest, as we have observed, that these gender expectations have exacerbated frustration among young men. This coincides with increasing drug abuse and cases of gender-based and sexual violence in conflict-affected areas and IDP camps.

Conflict also has long-lasting consequences. For many young men, war has become a way of life. Beyond military skills, many do not have employment or the capacity to compete in the job market. Many combatants see the end of hostilities with apprehension and feel that reintegration is impossible without proper support, economic opportunities and training. Some men also come back from the battlefield physically injured, which greatly limit their capacity to take back work and provide for their families.

War also leaves lingering mental scars. Boys and men, in particular, have experienced physical hardship, discomfort due to lack of food and disease, grieve due to loss of friends, and witnessed or engaged in violence. Many former fighters, on the Tatmadaw and EAO sides, have experienced mental distress in the battlefield. Gender expectations about masculinity, however, often prevent men from seeking help or discuss psychological trauma. Yet, even if these former soldiers were willing to discuss their mental health problems, the availability of mental health services in Myanmar is extremely scarce.

The overwhelming availability of drugs and the narcotic epidemic also disproportionately affects boys and men in many states such as Kachin and Shan. The lack of economic opportunities, the feeling that men fail at providing for their family, and insecurity are often mentioned as factors that encourage substance abuse and addiction in many IDP camps. In Kachin state, some of our interviews suggested that fostering drug addiction among young men was a counterinsurgency tactic by the Tatmadaw meant to weaken ethnic solidarity. When boys and men find work in places such as jade mines, harsh working conditions and easy access to narcotics put them in a heightened risk of substance abuse. In Kachin state, some people told us that drug use among the male population led to a greater level of premature deaths among males in their community. The sharing of syringes puts drug users, disproportionately men, at a higher risk of blood-borne infections such as HIV, Hepatitis C and Tuberculosis.

Social stigma against drug users makes it difficult for substance abusers to seek adequate treatment. The vast majority of drug users treated at national drug treatment centers are male (94.9 percent) between the ages of 25 and 39, and belong to the working class. A majority of them are Bamar and Shan nationals. In Shan State, many people we interviewed mentioned that EAOs draws drug users into a rehabilitation process, though it often serves as a recruitment channel as recovered patients are then enlisted into EAOs. Some drug users in Kachin states were also reportedly detained in local rehabilitation centers operated by NGOs to remove substance abuse habits. Young men often experience human rights abuses due to the harsh rehabilitation process conducted in undersupplied and understaffed facilities with poor medical resources.

Conflict also exacerbates gender imbalances in access to livelihoods. In Myanmar, labor market is already extremely gendered. Woman labor participation is extremely low compared to neighboring countries. Gender norms generally prevent women from taking on jobs that are too physical and hard, for example. Women thus tend to be over-represented in the informal economy, confined to unpaid, underpaid, and generally precarious informal and social reproductive work. When they manage to find work, women experience a wage gap of approximately 20 percent with men. Gender norms also indirectly prevent women’s access to land and inheritance. A report by Namati found that although women have legal rights to land ownership in Myanmar, the dearth of female administrators and the predominance of males in local administrative units often prevent them, in practice, from fully enjoying these rights. Without access to land, women have a more difficult access to loans and credits for livelihood opportunities.

Conflict creates uncertainties that tend to reproduce gender inequalities. In education, for example, insecurities related to war or criminality may prevent girls’ access to school. Our survey asked respondents whether educational institutions were available within walking distance from home. Table 1 shows that a majority of respondents in rural areas had no access to a high school or a vocational school and only half had access to a middle school within walking distance from home.

|

Table 1. Educational institutions available within walking distance

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

Rural

|

Urban

|

|

Primary School

|

71.6

|

72.7

|

|

Middle School

|

54.3

|

72.1

|

|

High School

|

38.7

|

68.6

|

|

Vocational School

|

12.7

|

32.5

|

UofT-IDRC Survey on the Delivery of Public Services in Chin, Kachin, Kayin, and Magwe, 2019.

While a lack of availability of schools certainly affects everyone, it is more likely to affect women. Our survey findings showed that the two most important challenges women faced when accessing education were related to security: the security of girls in their travel to and from school as well as security in the school environment (Table 2). Given distance from schools (table 1), this challenge of travelling to and from school is more likely to affect girls in rural areas. Quite interestingly, a gendered apprehension about women’s security was more important than a more traditional gendered expectation about the proper role of women (women should stay at home to help) in preventing girls’ access to school.

|

Table 2. Challenges for women to attend school

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

Agree

|

Disagree

|

|

Travel to/from school is unsafe

|

60.7

|

34.8

|

|

The school environment is unsafe

|

61.4

|

34.7

|

|

Women should stay home to help

|

46.9

|

46.1

|

UofT-IDRC Survey on the Delivery of Public Services in Chin, Kachin, Kayin, and Magwe, 2019.

Displacement also makes women particularly vulnerable. Due to widespread drug and alcohol use among displaced men, in the absence of them, women are often not only expected to be homemakers, but also to assume roles traditionally assigned to men, such as “protectors” and “providers.” The reversal of gender roles often creates tensions in the family and exposes women to domestic violence, including intimate partner violence. IDP camps provide little economic opportunities for neither men nor women. But for women, a lack of economic opportunities often means heightened risk of human trafficking. In Kachin and Shan states, for example, women have been trafficked for forced marriage and childbearing in China. A civil society activist we met described the lack of registration, common among ethnic minorities, as one key reason, “why ethnic women are subject to gender-based violence, migration, trafficking and discrimination.” Women’s League of Burma concur that lack of proper documentation and inaccessibility to immigration services had led to greater reliance on smuggling as a method of trans-border migration, heightening the risk of abuse of basic rights for female migrants.

Conflict and displacement also increase the chances of gender-based violence, often used as a war strategy. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights reported that the Tatmadaw’s military operations against the Rohingya and ethnic groups in northern Myanmar employed large scale, brutal, and systematic sexual violence as part of a deliberate strategy to intimidate, terrorize, and punish the civilian population. The same report also noted that women and girls were also victims of rape and other gender-based violence by members of the EAOs.

Conflict and displacement also increase gender-based violence because it creates spaces of impunity. A civil society activist on women’s issues pointed out that “if [NGOs] issue a complaint to the Tatmadaw, the usual response is to deny the occurrence and blame it on the EAOs.” While EAOs attempt to bring justice to perpetrators of gender-based violence among their ranks, many perpetrators are still inadequately sanctioned. As one member of the Kachin religious community revealed: “Where there are [Tatmadaw] battalions, no one comes out. [Villagers] are afraid. At night, no one dares.” Our survey found that less than half of the women would like to see more military presence in their area (48.2 percent). Interestingly, but not surprisingly, non-Bamar women and those who live in rural areas were the least likely to want more military presence in their community.

|

Table 3. Percentage of women would like to see more military presence in their community

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Rural

|

Urban

|

Bamar

|

Non-Bamar

|

|

45.8

|

54.7

|

65.8

|

39.3

|

UofT-IDRC Survey on the Delivery of Public Services in Chin, Kachin, Kayin, and Magwe, 2019.

Victims of gender-based violence are often terrified to report to the police as well. Our survey found that most women would rather report crimes to community leaders, rather than the police (Table 4). It also found that in both rural and urban areas women were particularly unlikely to report sexual crimes to the police in comparison to other crimes. Women often need assistance from local NGOs to accompany the victims to the police or report on their stead.

|

Table 4. Where do women go when they are victims of a…

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Robbery

|

Sexual Assault

|

||

|

|

Rural

|

Urban

|

Rural

|

Urban

|

|

Community leader

|

77.4

|

41.1

|

88.1

|

50.7

|

|

Police

|

19.2

|

47.3

|

8.8

|

34.8

|

|

Other

|

1.1

|

6.5

|

1.4

|

8.5

|

|

Do not know

|

2.3

|

5.1

|

1.7

|

5.9

|

UofT-IDRC Survey on the Delivery of Public Services in Chin, Kachin, Kayin, and Magwe, 2019.

NGO workers we met noted that victim-blaming still occurs when women and girls suffer from gender-based violence. In fact, the UofT-IDRC survey found very low levels of satisfaction of women for police services when they are suspected of a crime (14.3 percent) or victim of a crime (31.3 percent). In general, the survey shows lower satisfaction among women in rural areas. A civil society activist on women’s issues based in Yangon stated that such circumstances have contributed to the prevalence of trauma among women and girls in conflict-affected areas of Myanmar.

This text does not provide an exhaustive picture of the gendered impact of conflict, but highlights a number of issues that need to be tackled for a successful transition toward democracy and decentralization in Myanmar. There is a need to move away from gender-blind policy-making at the local level and recognize that decades of conflict and displacement have had gender-specific consequences. In conflict and post-conflict zones, there is a need to tackle men’s experience as soldiers both in terms of its economic, social, and psychological impacts. There is also a need to tackle women’s experience of conflict, which has made them economically precarious and vulnerable to sexual and gender-based violence.

Conflict has reinforced gendered norms and expectations and that democratization and decentralization will not automatically override them. Men are definitely over-represented in the public sphere, in the political institutions and in the peace process in particular. That being said, norms of masculinity may prevent men from talking about their particular experience of war and trauma. Policies and policy-making need to ensure the integration of disgruntled or marginalized men, otherwise, it may fuel further exasperation and lead to a return to conflict. The political elite, despite being male, can be divorced from foot soldiers’ experiences and perspectives. There is thus a need to open up a space for this kind of dialogue.

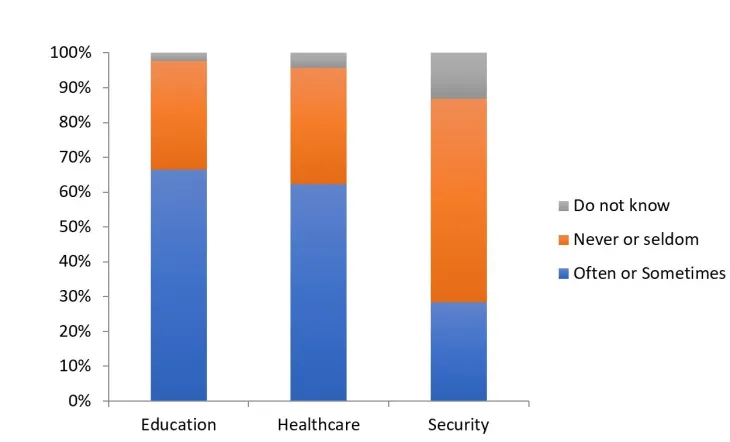

Decentralization will not necessarily benefit women either. Decentralization is often seen as beneficial to women as it allows higher accountability at the local level, and closer proximity of service delivery. Women also are usually associated with the domestic sphere, thus local government is seen as touching more directly on their daily interests and concerns. In terms of participation, local state institutions are conceived of as especially appropriate for women because of their lower barriers to entry. But decentralization may also perpetuate informal institutions, systems, and relations of power. In the 2015 elections, only 13.3 percent of the candidates were women, and local parliaments all have less than 10 percent of women MPs (with the exception of Yangon and Sagaing regions). In daily local governance, our survey found that, in the last five years, women felt the less involved in matters related to security, one of the most important issues where women’s voice should be the most present.

The peace process should also be more inclusive. While stakeholders of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement pledged for gender inclusivity, it is still very far from reaching the agreed threshold of 30% of female participants. A recent study by Mollie Pepper also found that despite the Myanmar government’s promise to foster greater inclusion of women, women continue to be marginal in the policy process. The same paper found, however, that women are key players in peace building because of their civil society activism, organized through ethnic women’s organizations.

In sum, stakeholders in Myanmar should continue to work towards gender mainstreaming in the governance structure and the peace process. Only then, will it be possible to address the social injuries experienced by various genders in conflict-affected areas, therefore making it possible to bring about a more robust peace in Myanmar.

Jae Park is a member of the research team of the University of Toronto-IDRC project on gender and decentralization. He is a Ph.D. student in Political Science at the University of Toronto. He studies civil wars and political violence.

Alexandre Pelletier is the research coordinator of the University of Toronto-IDRC research team on gender and decentralization in Myanmar. He is currently a SSHRC postdoctoral fellow at the Southeast Asia Program at Cornell University and holds a PhD from the University of Toronto (2019). His work focuses on questions of nationalism, ethno-religious conflict, and federalism in Southeast Asia, with a specialization on Myanmar and Indonesia where he has conducted extensive fieldwork.

Like This Article