In Part 2 of a 2-part post on digital conduct concerning Myanmar, Benedict Mette-Starke lays out practical digital communication considerations for Myanmar scholars and others outside Myanmar.

Considerations of ethics and responsibility continue to be challenging, to say the least (compare Brooten and Metro 2014; Chambers and Cheesman 2019; Chu May Paing and Than Toe Aung 2021). Several UN agencies with offices in Myanmar, for instance, have been criticised by a group of 22 Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) for their silence on the coup. In their presentation at the recent International Graduate Student Conference at University of Hawai’i, Manoa, Ma Chu May Paing and Ko Than Toe Aung (2021) have very well critiqued “white and/or Western” researchers of Myanmar who “theorize about […] us rather than amplify our voices” while also acknowledging intersecting colonialities at play in Myanmar. Different people hold different privileges in different situations. Those privileges bear upon ethical considerations or entail responsibilities. So, while it is still important to stay quiet at the right time, it is equally important to act, talk and stay in touch in light of recent events.

In Myanmar politics, including especially the Tatmadaw, there have historically been strong suspicions against ‘foreign interference’ (e.g., Egreteau and Jagan 2018). The recent announcement by the Central Bank of Myanmar (2021: 9) alleging an unregistered remittance and withdrawal of funds by Open Society Myanmar could be read in that vein. Given those suspicions, keeping contact with people inside Myanmar without precautions is just as insecure and potentially even more risky than communication within the country. The risks highlighted in the RMMG, and analysed in part 1 of this post, extend to those who engage with Myanmar from afar. Hence, part 2 will deal with some practical advice. It is not meant to provide quick-fix solutions but rather signposts leading to more in-depth engagement with digital security as everyday practices.

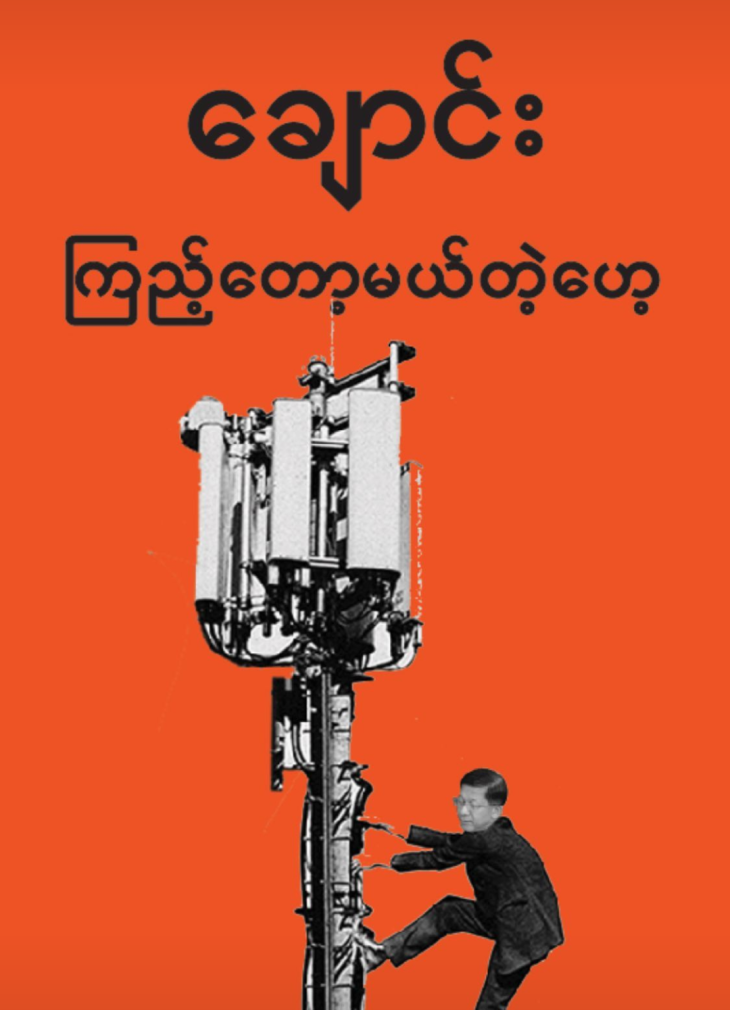

Keeping your communications with and material concerning people in Myanmar secure should be a guiding principle. Ensure that only you can read your communication by using encrypted messengers such as Signal, Wire, and, in case of emergency without internet access, Silence SMS or pre-established codewords, as the RMMG suggests. Silence SMS works with the same encryption techniques as Signal but uses them to encrypt text messages sent over the regular mobile network rather than the internet. Signal further allows for disappearing messages which can be enabled in a conversation’s settings for sensitive communication.

As long as there is some internet connectivity, even in a wide-ranging but non-total shutdown, there is a very slim chance of messages getting transmitted through remaining connections utilizing mesh-messengers such as Bridgefy or Briar. None of these apps are ideal. Bridgefy seems to have patched their known vulnerabilities (which made de-anonymization of users possible; compare Albrecht et al. 2020) and claims to be using e2ee as of app versions after October 2020. Unlike Bridgefy, Briar is open source and uses further encryption measures but does not establish a synchronous network. Instead, messages are forwarded from device to device, making it potentially slower. While these apps can be vital to keep communication up, only consider installing those and getting your contacts’ details for them if strictly needed if you are not in Myanmar, as setting them up takes up valuable time and bandwidth from your contacts at a time when both are rare. Bear in mind that limited connectivity means larger files such as audio, image, or video files are not easily transmittable.

To guard against illegitimate access, to which those outside Myanmar can also fall prey, ensure that no one can access your accounts clandestinely. Many services, including Facebook, allow for logouts on all previously connected devices. This can be a first step; otherwise, if adverse agents get a hold of a device, either physically or remotely, they could gain access to accounts and contacts. Activate 2FA in the same settings. Consider regular password changes so that a stolen or insecurely stored password does not pose as significant a risk. The easiest way to do this is through using a password manager which securely stores your passwords, such as KeePassXC (computers, with browser plug-ins for Firefox and Chrome), KeePassDX (Android), and KeePassium (iPhone), as the document recommends. Those programs create encrypted databases that you can then keep synchronized copies of on your cloud storage. You will only need to remember one hard-to-guess password to unlock your database. The apps can then fill in your details whenever required, even checking whether it is a legitimate website asking for them if you set them up that way.

Keep all your software up-to-date to avoid security loopholes that third parties could exploit. It is often easier to do so through the respective app stores, which take care of regular updates on standard devices. Therefore, if security loopholes have been identified, they can be patched. If you do not use the stores, you need to make sure to update your apps manually.

Ask your contacts, if appropriate, if it would be helpful for them to check in with you as their ‘buddy’ regularly. While people outside Myanmar are ideal ‘buddies’ because they are in a different location and hence, for instance, less likely to be arrested, their usefulness is reduced in case of a shutdown. Remember that emails are not, by default, encrypted. They can easily be intercepted and read by third parties. The easiest way to communicate through encrypted emails is by both parties using ProtonMail, a free-of-charge service of a Swiss company that also offers free-of-charge VPN services. While VPN is crucial for people in Myanmar now, they are less critical for anyone outside Myanmar unless they fear targeted surveillance, want to cloak their Internet traffic, or circumvent restrictions themselves.

Some initiatives have been to sponsor paid VPN services for people in Myanmar, top-up mobile phone balance, and donate to various Civil Disobedience campaigns. While those and other kinds of donations can be a great form of support for meritorious causes, they can have varying consequences beyond that. Because of the differentials established in donations (compare, e.g., Kawanami 2020) and the potential suspicion against those who receive outside sponsorship, follow the lead of your contacts in the country. Remember that the VPN services you use need to be trustworthy, as they can monitor internet traffic unless they specifically impose encryption measures which you need to trust them on. The RMMG recommends—and thereby signals its trust in—the free-of-charge Psiphon (particularly for iPhone) and TOR browser / Orbot.[1] You can judge a VPN’s trustworthiness not by the money you pay for them but by their terms of service. Significant factors include minimal logging of internet traffic (or at least very regular log purges) and traffic encryption as far as possible. Logs should ideally be limited to those necessary to provide the VPN service, such as those necessary to check how many people are logged in with the same credentials at the same time. If you want to sponsor a VPN account rather than recommending free ones, listen to your interlocutors, read the services’ privacy policies and terms of service and check whether they encrypt traffic and log minimally.

While collecting data and keeping records is especially important now, keep in mind that some of this information may be sensitive. In the worst case, improperly stored records and data could be used for persecution and extortion. Safety considerations should include storage, transfer, as well as with whom to share material.

Records should be encrypted in storage and transfer. Data is ideally stored encrypted on hard drives if outside Myanmar or, if necessary, e.g., for co-operation, encrypted on secure cloud servers. BoxCryptor and Cryptomator specifically offer cloud storage encryption. The most versatile software to encrypt things in digital storage, in general, is VeraCrypt. While most new iPhones and Android phones should be encrypted by default, if passphrases are used to lock them, you can go to Setting>Security and look for encryption on Android or System Preferences> Security&Privacy and check the FileVault tab on iPhones to make sure.

Be aware that not everything that is posted on social media is intended to be public, and even public information is not necessarily safe to use and spread.[2] If something is posted to one’s Facebook “friends,” it is better treated as sensitive. Do not publish or present identifiable screenshots or images of people’s faces and other identifying marks such as tattoos. Social media posts are highly identifiable and persistent. Anonymising them (Unger, Dilger, and Schönhuth 2016: para. 13) and keeping confidentiality is especially challenging (Ess and AoIR Ethics Working Committee 2002: 5). Facebook posts, for instance, have a URL, a timestamp, a profile picture, a profile ID, a post-description, and reactions, to name a few identifying markers. Anonymising a post would require separating all those without putting them back together again to re-identify a post. This is even further complicated if the posted text, for instance, is relatively unique and can simply be searched for.

Likewise, reverse image search engines allow people to search for photos, e.g. similar to profile or portrait shots. So, while de-identification is possible, anonymisation is nearly impossible. Therefore, explore options to present material in other ways than through screenshots or pictures of identifying markers, such as using tools to irreversibly and effectively blur identifying marks in people’s images. Do not publish personal information about people you know in Myanmar anywhere online, including on Google Docs, where anyone in possession of the link could access them as they could be used for incrimination or prosecution unless specifically asked to do so by them.

Academics should educate themselves on the ethics of using social media material in research. The Association of Internet Researchers’ ethics guides (Ess and AoIR Ethics Working Committee 2002; franzke et al. 2020) and Leanne Townsend and Claire Wallace’s (Townsend and Wallace 2016) guide are good English-language works to start from. Be aware that social media research may require the approval of your Internal Review Board (IRB). In any case, it is your responsibility to protect the privacy and safety of your interlocutors.

Many guides concerning protests or cybersecurity are in circulation, both in Myanmar and in English. Readers interested in further security measures can find Michael Caster’s article with additional resources on Vice. Guides, in both Myanmar and English, and the most pertinent software as a last resort can be accessed at https://bubbles.sevensnails.com/ as per Sam Gregory. Lastly, Tactical Tech’s resources provide great background reading on several digital activist issues in English. For those interested in technical issues from a (mostly white and male) UK computer science perspective, Computerphile holds many interesting background videos. Additionally, Free Expression Myanmar published a legal protest guide on February 8, 2021 both in Myanmar and English, which makes for a formidable background reading.

Benedict Mette-Starke is a PhD candidate in social and cultural anthropology at the University of Konstanz, Germany. He has conducted ten months of research on digital rights activism in Myanmar in 2019 and 2020.

Notes

References