Emily Fishbein and Kelvin Sinpraw (pseudonym) show how a Kachin tradition defies borders.

From February 12 to 15, hundreds of people gathered in Bordumsa, a village in the Changlang district of northeast India’s Arunachal Pradesh, to celebrate Manau, a Kachin traditional festival. Women in bright, diamond-patterned outfits jingling with silver neck and waist ornaments lined up next to sword-bearing men in longyis and tasseled headbands. Twice a day, they sang and danced in spirals around a set of colorful pillars that serve as a Kachin cultural icon.

Manau carries deep cultural significance for Kachin people, but in Myanmar, its celebration has been overshadowed by war since the collapse of a seventeen-year ceasefire between the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) and military in 2011. The ensuing clashes displaced more than 100,000 people, leading many Kachins in Myanmar to boycott the event ever since.

This war has only intensified since the February 2021 military coup, pushing the prospects of a festive Manau within the country even farther into the distance. But the Kachin ethnic identity goes beyond international borderlines and has managed to endure these upheavals in northeast India, where a small Kachin community known as Singphos has kept the tradition going

Singphos, together with Jinghpaws in Myanmar, make up the largest of six major Kachin tribes along with Lachik, Lawngwaw, Lisu, Rawang and Zaiwa, and like many ethnic groups, their identity predates colonial borders.

Kachin people began migrating westward from the Hukawng valley, Sumpi Yang and Putao regions of today’s northern Myanmar in the 16th and 17th centuries, according to Kachin linguist Langjaw Kyangying of Myitkyina. In Assam, they were some of the first people to take up tea cultivation, which remains a popular Singpho livelihood today. Recruited by the British Imperial Army, Singphos also played an active role in India’s struggle for independence.

Singphos were first divided into a separate administrative territory from their Kachin kinfolk with the implementation of the Government of India and Government of Burma Acts in 1937. India’s independence from Britain in 1947 and Burma’s a year later further set the two communities on distinct historical paths.

Today, Singphos are thought to number in the tens of thousands. Dispersed across the Changlang and Namsai districts of Arunachal Pradesh and the Tinsukia district of Assam state, they live closely with Tai Khamtis, a population known in Myanmar as Hkamti Shans. In Arunachal Pradesh, Singphos are listed among sixteen “scheduled tribes,” granting them certain protections under India’s constitution.

Their Manau festival, named Shapawng Yawng after the legendary forefather of Kachin people, has been celebrated annually since 1985. Ten interviews conducted during a visit to this year’s festival and by phone suggest that it offers a rare opportunity to bring geographically-dispersed Kachin people together, and also serves as a vital means of cultural preservation.

“As time goes on, some people don’t write their titles as Kachin. Some people intermarry, change their titles and forget their identities,” said Singdu Nong Marip Singpho, a former president of the Singpho Development Society, who like many Singphos uses his ethnic group as his surname. “Before, there were Singphos in different places, but we didn’t know each other and had no reason to gather together. But after forming this Singpho Development Society and organizing the Manau year by year, even if someone forgets what tribe they are, when they see the Manau, they remember.”

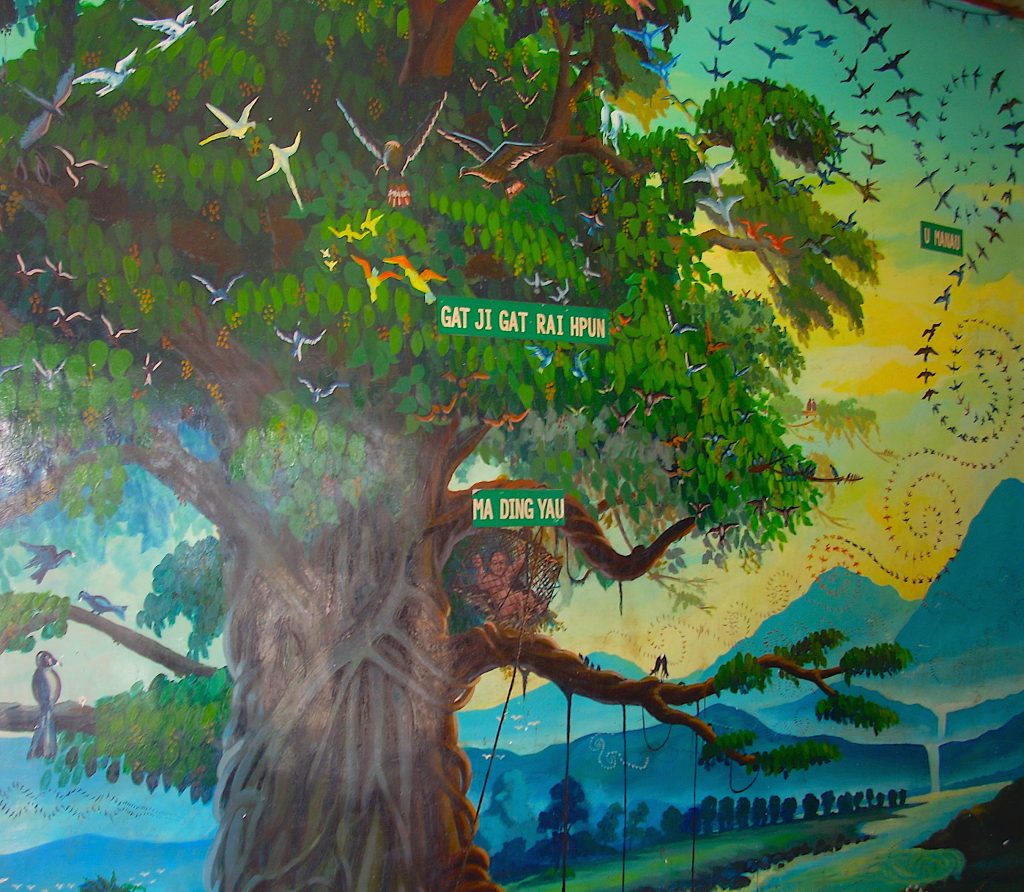

Kachin folklore offers various legends to describe the origins of Manau, most of which trace the dance’s patterns to the flight of birds. According to a version printed in a Singpho Development Society pamphlet and recounted during two interviews, the dance was introduced to humans by a man named Mading Yau.

As the legend goes, Mading Yau had the ability to understand the natural world but was poorly understood by his own community. Banished to a basket hanging from the branch of a banyan tree, he watched birds gather the tree’s fruit and learned their songs, language and flight patterns, which he later taught to the people. According to some versions of the legend, the dance represents the coming together of all the birds in the universe.

Manau festivals traditionally commence with the sacrifice of a buffalo to ancestral spirits known as nat jaw. Although the practice continues in India, it has been abandoned in Myanmar, where most Kachins now follow Christianity. The dance encircles a set of four to twelve pillars, each decorated with its own pattern. Two lines led by Naushawng – men wearing robes and hornbill bird headdresses – move in swirling patterns, singing and dancing to music played on drums, gongs and wind instruments.

Manau festivals can be held for a variety of purposes including to celebrate prosperity and appeal for further wealth, prepare for war, and celebrate wartime victory. According to Singdu Nong, the Shapawng Yawng festival incorporates several purposes. “We dance to remember our forefather Shapawng Yawng and ask for his blessings, wisdom, wealth and protection,” he said.

In her 2005 doctoral thesis for the School of Oriental and African Studies, Dr. Mandy Sadan describes Manau festivals from before the British colonial era as “part of a deeply significant ritual system around which many aspects of socio-cultural and political structure cohered.” In her book Being and Becoming Kachin, published in 2013, she elaborates that these days-long festivals were most strongly defined by offerings to spirits and recitations of the genealogical origins of the host, performed by spirit-priests known as jaiwas.

Held for reasons including to mark moments when lineages separated or when communities came together to affirm their kinship, these festivals also enabled Jinghpaw chiefs to consolidate their socio-political positions, according to Sadan. Her research found that between World War I and World War II, the role of Manau shifted, as British colonial administrators began organizing the festivals as a way to strengthen their relationships with Jinghpaw chiefs and headmen and to expand their reach in Upper Burma and the Kachin Hills. By the late 1920s, the British were also using Manau to announce key policies, and the festival’s animist traditions were increasingly overshadowed by its administrative functions.

When Burma gained independence from Britain, the central government designated January 10 as Kachin State Day and began organizing Manau festivals in the state capital of Myitkyina to recognize it. Then in 1961, the KIO began its revolution for political autonomy and these events ceased. Instead, the KIO held a Manau festival in its territory to mark the outbreak of armed hostilities. According to Sadan, the festival was the first to explicitly celebrate a pan-Kachin, or Wunpawng, ethno-political identity representing six Kachin subgroups.

With the signing of a ceasefire between the military and KIO in 1994, Kachin State Day festivals in Myitkyina resumed, at times attended by both the KIO and military as well as military-aligned KIO splinter groups. But in the years leading up to the ceasefire’s collapse in 2011, the military increasingly took control over these events – an act described by local media outlet Kachin Newsgroup as “akin to cultural genocide.”

In February 2011, meanwhile, the KIO held its own Manau festival at its eastern regional headquarters of Mai Ja Yang to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Kachin Revolution Day. By this time, the military had restricted travel to KIO territory, and those attending the festival from areas under its administration had to take a circuitous route via China. War between the military and KIO resumed that June, and Kachin State Day festivals in Myitkyina have since seen a heavy military presence as well as strong opposition from Kachin civil society. At times, Kachin activists have instead used these Manau grounds to hold large protests against armed military offensives.

As Manau festivals in Myanmar remain shrouded in controversy, Kachin populations in other countries have carried on the tradition. In the Dehong Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture of China’s Yunnan province, home to a significant community of Jinghpaw and Zaiwa-speaking people collectively recognized as Jingpo, the festival is known as Munao Zongge and is organized by the Chinese government. Now in its 39th year, it was most recently held this February and included 60,000 attendees according to Chinese state media.

The festival is also celebrated in the village of Banmai Sammaki in Thailand’s Chiang Mai province. Established in the late 1970s by ex-KIO members, the village acquired official status in 1982. Shortly after, its residents began holding Manau festivals on the birthday of the late Thai king Bhumibol Adulyadej; the most recent of these festivals was held in 2018.

India’s Shapawng Yawng festival, held every February, is organized by the Singpho Development Society. According to Singdu Nong, the festival enables Kachins across the India-Myanmar border to reconnect. “Even though we settled in different countries, we hold this Manau to remember that we are all of one blood,” he said.

During this year’s festival, some of those in attendance were Jinghpaws from the Hukawng valley, many of whom are closely related to India’s Singphos. Along with vendors from Myanmar who came to sell souvenirs, they mostly traveled overland, briefly entering Sagaing region from the Hukawng valley before crossing the Pangsau pass.

The mountainous border crossing is located on Ledo Road, constructed during World War II to enable the Western Allies to deliver support to China in its fight against Japan. Then, it was nicknamed “Hell Pass” for its difficult terrain. Today, although a bilateral agreement reached in 2018 between India and Myanmar allows local people to travel visa-free within 16 kilometers on either side of the border, travel further inland remains otherwise restricted to the public – with the exception of the Shapawng Yawng festival, when visitors from Myanmar can apply for a permit through Indian border authorities to attend the festival on the condition that they return immediately after.

The festival saw particularly large participation from Myanmar for its 25th anniversary in 2009, when those who joined included jade tycoon Sutdu Yup Zau Hkawng. Two years later, however, the Kachin political context dramatically changed with the collapse of the KIO-military ceasefire; since the coup, fighting has further escalated amid a widespread armed uprising against the junta.

According to Singdu Nong, such grand events as the 2009 festival are no longer possible due to a tightening of the issuance of border passes by Indian authorities. “The government is very strict about how many people are coming,” he said. “We used to formally invite hundreds of delegates [from Myanmar] with permission from the [Indian] government, but because of the political environment, this year we didn’t invite them. Even if we were to invite them, they wouldn’t have been able to come.”

For Kachins from China and other countries, attending the festival is even harder due to a history of territorial disputes between India and China in the Tawang district of Arunachal Pradesh. Foreign nationals wishing to visit the state must apply for a Protected Area Permit through India’s Ministry of Home Affairs.

Nnau Brang Nan, a lawyer from Innao, Arunachal Pradesh, described a situation in which Kachins and other ethnic nationalities whose populations span borders became “sandwiched” by geopolitics. Unable to legally visit his relatives in Myitkyina by crossing the land border, he is instead required to apply for a visa through the Myanmar embassy and fly into the country, while Kachin nationals living in Myanmar face a similar dilemma when visiting India. “We have been victimized as an ethnic border race – not only Kachins, but Chins, Nagas, [and other] Tibeto-Burman groups,” he said. “We have to go round and round…That feeling is very painful.”

Kachins from Myanmar already living in India are more easily able to join the Manau festival. This year, around a dozen university students traveled from Shillong, the capital of northeastern India’s Meghalaya state, singing songs around a campfire late into the night with their Singpho peers. “After so many years being far away from our own community, this is the first time coming back and getting this vibe of Kachin. It is a very warm feeling,” said Tsam Rawng Seng Maji, who studies political science at North-Eastern Hill University.

But he and others expressed concern that the Singpho cultural identity is disappearing. “My main wish is to be united with this Singhpo community and grow with the Singhpo community… [and for the] language and culture not to be erased or vanish,” said Mung Ran Awng, a physics student at the same university.

Also joining the festival were a handful of Kachin missionaries from Myanmar who live in India. While the vast majority of Kachins in Myanmar are Christian, most Singphos practice a combination of Theravada Buddhism and the worship of ancestral spirits.

Religion appears to be a somewhat sensitive issue between the two communities. “Even when hanging out with friends or visiting neighbors, we have to speak very carefully when the conversation goes to religious topics,” said Hka Tawm Maran, who runs a Kachin Baptist mission school in Inthem, Assam State. Still, she described a general understanding that has developed. “We cannot preach the gospel outside of the [school] compound, but we can practice our religion freely, because they understand that we are Christians and we are also doing our worship,” she said.

Nnau Brang Nan, the lawyer from Innao, also said that the two communities were able to overcome their religious differences. “Here in India, we have no religious connections with Kachins in Burma, but the thing making us connected across the border is the culture, tradition, language and belongingness from Majoi Singra Bum,” he said, using the Kachin name for a mountain in today’s Tibet.

In addition to its social functions, the Shapawng Yawng Manau festival has encouraged the sharing of Kachin traditions. In 1995, naushawng from Myanmar trained Singpho men to lead the dance. Then in 2009, Langjaw Kyangying, the Kachin linguist from Myitkyina, composed a song for the festival whose lyrics describe the westward migration of Kachin people into today’s northeast India.

The festival’s keyboard player, Jau Lat Manje of Margherita, Assam State, studied under a keyboard player from Myanmar in 2018 and then on YouTube. “I was learning music since I was young, so I thought maybe I could try it,” he said. “Now it’s my responsibility. It’s been five years that I’ve been involved, and it feels great.”

One role still lacking among India’s Singphos is a buffalo horn player, a rare skill across Kachin society. This year, Salang Magawng Awng joined the festival from Myitkyina, climbing a tall bamboo tower to play three melodies which helped direct the dance’s movements.

In further efforts to promote Kachin culture and traditions, the Singpho Development Society organized competitions including in folk tale and essay writing, drawing, and dance. The latter was performed during nightly stage shows alongside singing and a fashion show featuring traditional costumes and talents.

The main event on the last night was a performance by Anong Singpho, a Bollywood singer and songwriter who also composed the popular Kachin love song Yu Saalai. In an interview after his performance, he said he hopes to inspire other Singpho youth. “We have so many different kinds of people in our society. Some are good in sports, some are good in music, and some go in different directions – peer pressure, drugs, opium, anything which can harm them and harm their society,” he said. “I hope that some youngsters can take me as a role model.” He is now working on his second Singpho song – a particular challenge because like many Singpho youth, he is not fluent in the language. During the festival, youth from India and Myanmar often spoke English for this reason.

Singphos are not alone: the government of Arunachal Pradesh counts 26 “major tribes” and 110 “sub tribes” in the state, each with its own language or dialect. In recent years, however, the state government has taken initiative to promote this diverse linguistic and cultural heritage. In 2022, it launched mother tongue instruction in eight languages alongside Hindi and English. Although Singpho was not among them, the chief minister invited all ethnic communities in the state to prepare textbooks in their mother tongue. The state government has also allocated funds toward the celebration of traditional festivals since 2020, and in January of this year, announced plans to build an Indigenous prayer hall in every district.

“In Assam, we do not have facilities regarding our literature and the value of our identity, but in Arunachal…we have the opportunity to promote our culture, identity, language and literature,” said Singdu Nong.

Authors’ note: Edith Mirante contributed to this report.

Emily Fishbein is an independent writer who focuses on underreported issues related to Myanmar using a collaborative approach.

Kelvin Sinpraw (pseudonym) is from Putao, Kachin State, Myanmar and is currently pursuing a degree in political science at the ICFAI University in Shillong, India.

Like This Article