Rosalie Metro discusses how Myanmar government textbooks can be used in innovative ways.

“If students start to question whether King Bayinnaung was a good leader…will they start to question whether their leaders today are good?”

It was the end of a day I’d spent in Mae Sot, Thailand, with a dozen teachers from migrant schools, as well as thirty more Zooming in from inside Myanmar or on the border. This daylong hybrid training on methodologies of teaching history, based on ideas I describe with my colleague Aung Khine in our chapter in the recent edited volume Teaching for Peace and Social Justice in Myanmar, built on work I’d been doing since 2001 about how to teach multiple perspectives on history in order to promote reconciliation. Yet the current situation demanded fresh approaches. We’d been working on new ways of using Myanmar government textbooks in Myanmar’s post-coup classrooms; in particular, we’d focused on a primary school text about King Bayinnaung.

This text explains how great Bayinnaung was, and how he did the same three things that all the ancient bama kings supposedly did. These are, not coincidentally, the same things the Myanmar military claims to do currently: strengthen the economy, unite the national races, and propagate Buddhism. This limited description is one of the many myths that dominates government textbooks. But at our training, the teachers worked in teams to do what I call “reading textbooks upside down and sideways”: using them contrary to their intended purpose to broaden students’ perspectives. They’d generated role plays in which the conquered Mon people talked back to King Bayinnaung, they’d come up with questions about the textbook authors’ biases, and they’d created lessons that invited students to test the textbook’s theories against alternate evidence.

Their work was so impressive. Nonetheless, this teacher’s question caught me off guard. She sounded concerned but also hopeful. Yes, I answered. If we teach students to read every text critically and invite them to form their own opinions about “heroes,” they are likely to turn those analytical skills on the current situation. That could be risky, for both students and teachers, and teachers would have to determine for themselves how much boundary-pushing was safe. Whether it was worth the risk depended on their purpose for teaching history.

I start many trainings by asking teachers: What is the purpose of teaching history? What would the authors of Myanmar textbooks say? What would your teachers have said? What would your organization or school say? And what do you think is the purpose of teaching history?

History textbooks produced by the Myanmar Ministry of Education before 2010 used to start with a foreword that explained that their purpose was to promote union spirit and patriotism. Despite the partial revision of this curriculum, textbooks are still oriented toward that goal. They tell a story of bama Buddhist rulers leading other “national races” toward unity and prosperity. They leave out the conflicts among those groups, as well as most of the accomplishments, cultures, religions, and languages or other ethnic groups. Textbooks produced by EBEPs connected to the Karen National Union, the Shan State Army-South, and the Karenni National Progressive Party prior to 2010 provided alternative facts but a similar narrative structure: the bama Buddhist rulers were the enemy, and the histories of sub-ethnic or non-dominant political groups were often minimized. In all cases, a one-dimensional view of history was presented.

In 2016, textbooks revised with the support of UNICEF, the Japan International Cooperation Agency and the Asian Development Bank started to be released. These organizations prioritized peace and social inclusion. The revised textbooks compromise between union spirit and patriotism on the one hand, and peace and social inclusion on the other, by editing out any mention of ethnicity from the primary level history textbooks. No longer are Anawrahata or Bayinnaung identified as bama, no longer are they battling with/uniting with the Mon or Shan kingdoms. There are only myanma tainyintha and nameless enemies. Personally, I don’t think this solves the problem, as students will learn from their families about ethnic tensions lasting until today; this approach, while well-intentioned, just sweeps problems under the rug.

But to teachers, promoting “patriotism and union spirit” or “peace and social inclusion,” are not the only reasons for teaching history. When I ask them what their own teachers were trying to accomplish by teaching history, they say things like, “make me memorize information” or “help me get a good exam score.” When I ask them what their own purposes for teaching history are, the answers vary: “tell students the true facts” is always popular; “help them learn from the past so they do not repeat mistakes” is often mentioned; and “show them the value of diversity and their own ethnic identity” is also raised.

Which methods and materials we choose for teaching history depends on the purposes we embrace. As I explain to teachers, there is no politically neutral history curriculum. There are so many historical facts that no textbook could include them all, and so what is put in and what is left out depends on the author’s purpose and biases. If we don’t consider our purpose carefully and reflect on our own biases, we will probably default to the way we were taught, or to the dominant ideologies in our society. If we are looking to change our society, we will have to think carefully about what kind of change we hope to make and why.

To return to the teacher’s question: do adults in Myanmar—or in my own country, the US, for that matter—want students to think critically about their own leaders? My former president, Donald Trump, said a clear no: he wanted the history of the US to be taught in a way that promoted patriotism, telling students that the US was the greatest country on earth, and whitewashing anything negative, like slavery or the genocide of indigenous people.

When I taught history in US high schools, I wanted my students to think critically and to hear the voices that had been left out of the curriculum. As a white person who had racial privilege because of the historical and ongoing oppression of people of color, I wanted to teach in a way that led to a more just society. But the administrators of the schools I worked in, my students’ parents, and political leaders did not always agree. I could not always choose my textbooks, or the tests that were used to assess my students, or the circumstances that interfered with my students’ ability to focus on school.

Myanmar teachers have many more factors outside of their control. The coup may have displaced them; they may be part of the CDM boycott of government schools; or they may need to continue teaching in government schools either for financial reasons or because they feel it’s their responsibility to continue educating youth. How much leeway they have to adjust the way they teach history depends on many factors, including whether they work for Myanmar government schools, Ethnic Basic Education Providers (EBEPs), migrant schools in Thailand, or private schools. Despite the constraints they may face, I deeply believe in the agency of teachers and their ability to keep their students’ best interests at heart.

While teachers in government schools must continue using state textbooks, many EBEPs and migrant schools also continue using Myanmar government textbooks even if they don’t agree with their ideological orientation. Their students may try to matriculate inside Myanmar and will need to know the answers to the exams. Or they may not have alternative curricula available. That’s what inspired me to do this series of trainings on reading textbooks “upside down and sideways.” Teachers may have to keep using these imperfect materials, but they can do so in creative ways that broaden the interpretive possibilities for their students.

All the same, they must keep the constraints and possibilities of their situations in mind. I often have teachers brainstorm the difficult things they can’t easily change about their teaching contexts (e.g., their salaries are low; students don’t have enough food; there are COVID-19 restrictions) as well as existing opportunities and possibilities (e.g., they have supportive colleagues; digital technology makes sharing resources easier). I write these on chart paper and keep them on the walls as we talk about teaching history, so we don’t lose sight of the realities they are facing.

Once we’ve talked about their current situations as well as their chosen purposes for studying history, I ask them about negative and positive experiences they’ve had studying history. Their responses often reveal deep emotion. On the negative side, they talk about being forced to memorize “facts” they knew weren’t true or complete, and having their ethnicity or religion ignored. On the positive side, they express gratitude to the teachers who worked against the system to teach more inclusive history, and how much they enjoyed the opportunities to collaborate with peers or be more active in their learning. We use these positive and negative experiences as our guides, considering how they can leave behind what didn’t work for them, and build on what did, in their own classrooms.

Then comes the fun: experimenting with how they can turn textbooks “upside down and sideways” to expand students’ experiences. Knowing that women and poor people are usually left out, we invent role plays that imagine their perspectives back into histories of wars and kings. What did the soldier’s wife who was left at home with five kids think of King Bayinnaung’s war? Historical sources are extremely limited on such questions, and there’s no clear right or wrong answer. But questions like this expand students’ thinking and open the question of how war affects women and children today.

These new methods do not always come easily. I have observed that it is easier for teachers to embrace active learning methods and child-centered education than it is for them to adjust their purposes for teaching history. For instance, one team of teachers designed a lesson on General Aung San that, while it vastly improved the instructional design of the textbook lesson, still asked students a leading question: “What do you admire about General Aung San?” This kind of question forecloses the possibility of criticizing a leader about whom many valid criticisms exist. Other teachers in the training gently raised this point, supporting their colleagues who had created the lesson while also encouraging them to think more broadly.

There are also important questions about when students should start learning about disturbing events such as wars and violence. The text about King Bayinnaung is from the 1st Grade Social Studies textbook, which students use when they are around 6 years old. These lessons on the ancient kings were moved from the old 3rd Standard to revised 1st Grade textbooks, for reasons I don’t understand. Some teachers in the training felt that young children couldn’t understand conflicts well and that textbooks that covered war in early grades could use additional context.

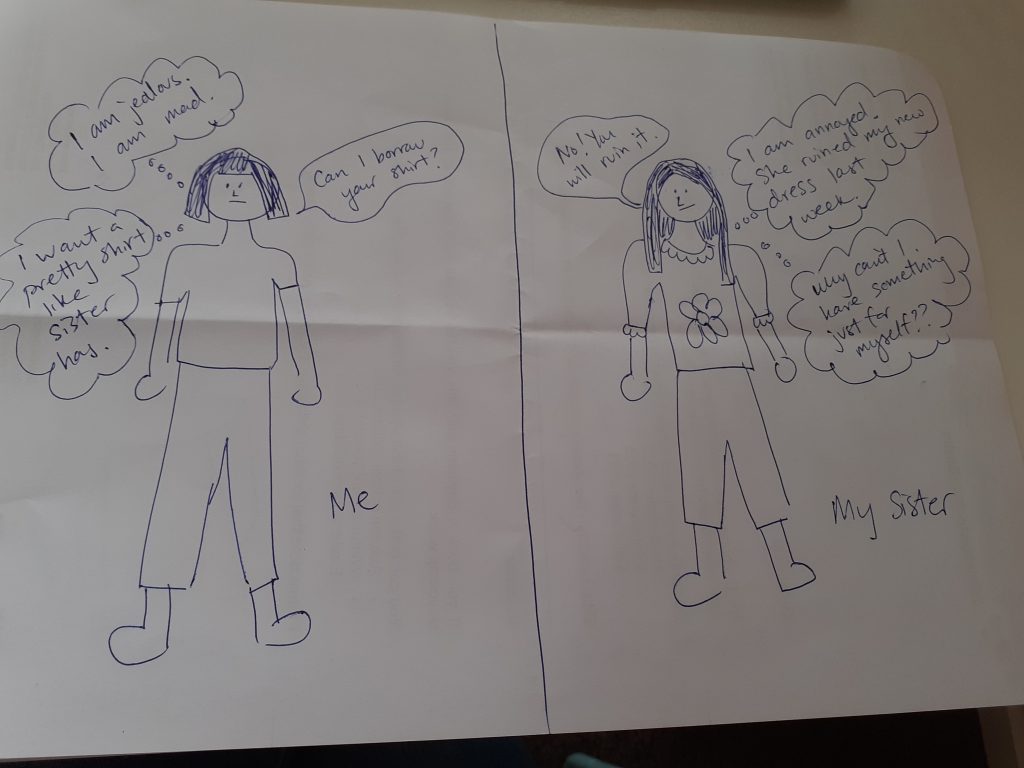

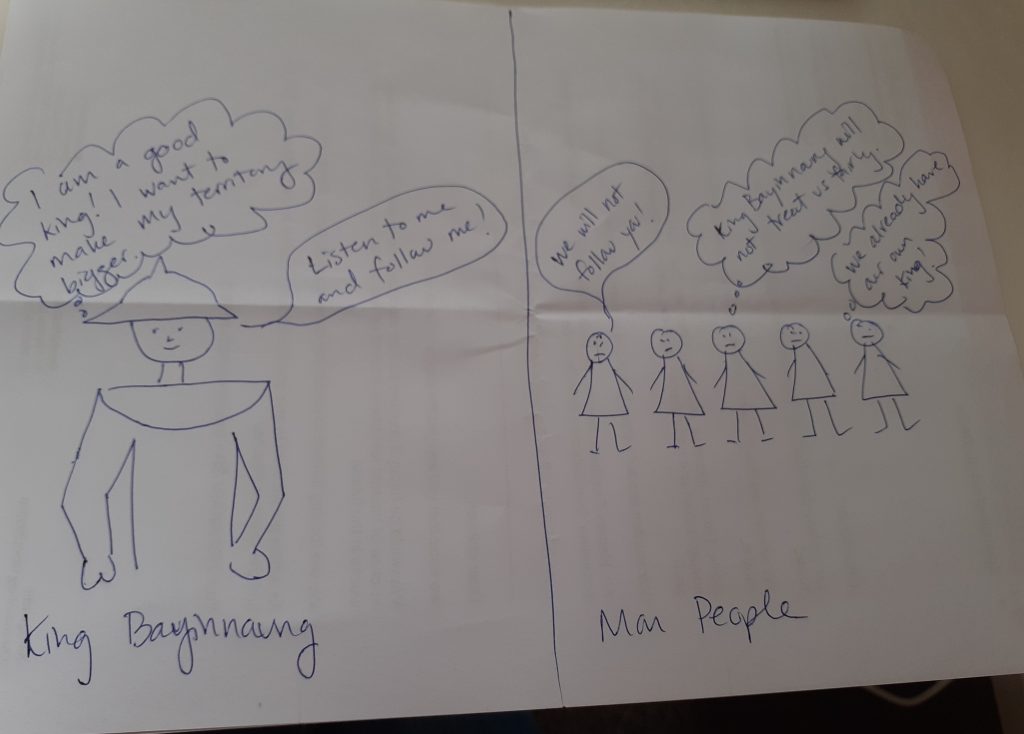

In response to this point about children’s developmental level, I shared with teachers some activities to help even young students develop their understanding of multiple perspectives. For instance, students could divide a paper in half and draw pictures of a time they had a conflict with a friend or family member to show the distinction between their own view and the other person’s view of the situation (see Figure 1—I have recreated these drawings based on what teachers created in the workshop to avoid the danger of their identities being revealed). They could then brainstorm solutions to their conflict. Through this activity, students could more easily imagine the different perspectives of, for instance, King Bayinnaung and the leaders of the areas he attacked (See Figure 2), as well as imagining other ways the conflict could have been resolved. We also shared ideas about positive ways teachers could add to the curriculum, for instance by covering the cultures, foods, dances, music, and traditions of various ethnic groups, so that they do not come to see certain groups only as victims of oppression, but also as leaders and innovators.

Unfortunately, it is a dangerous time to be a teacher in Myanmar and along its borders. Some would say that changes in teaching methodology can wait until there is peace and democracy. While teachers must take care of themselves first, waiting for total stability may take decades. That’s why I am eager to work with any teacher who wants to teach history to promote critical thinking, inclusion, and justice. Many teachers may face constraints in doing so currently. But the ones that are able to embrace new visions for the purpose of teaching history can make a huge difference in their students’ lives. History is so intimately connected to people’s sense of identity and their perceptions about the future; to deny students the opportunity to study history is to restrict their ability to understand how they fit into their society, and to limit their ability to solve problems in the present.

Even if some teachers are ready to change, is society as a whole? Are the leaders of the SAC, the NUG, ethnic armed organizations, or the Thai government ready for students to question the histories that are taught? These are not my questions to answer. But my impression of this new generation, which has seen the trauma and upheaval caused by the ideologies of militarism and narrow nationalism, leads me to this conviction: the students themselves are ready.

Rosalie Metro is an anthropologist of education who has been working with teachers from Myanmar since 2001. She holds a Ph.D. from Cornell University in Learning, Teaching, and Social Policy, and she is currently an Assistant Teaching Professor in the College of Education and Human Development at the University of Missouri-Columbia, USA. She is also the author, with Aung Khine, of Histories of Burma: A Source-Based Approach to Myanmar’s History.