Hitomi Fujimura explores how Karen Baptists understood “modern knowledge” in nineteenth-century America.

This essay is about relatively unknown ‘modern’ experiences by locals of Burma who sailed to the U.S. in the mid-nineteenth century. These accounts have never attracted scholarly or public attention but are full of lively, first-hand perspectives. The stories below demonstrate how these local experiences were not necessarily confined to the colonial framework. They will help us learn the unknown past through locals’ own eyes, revealing that some Karen Baptists witnessed the latest technology in 1840s and 1850s America. Those Karen converts interpreted the technology and new way of life that we often characterize simply as ‘modern’ or ‘advanced,’ as incomprehensible, superhuman, and thus divine.

Scholarly discussion often equates the arrival of modern scientific technology in Asia with the expansion of Western colonization (for classic, yet well-known arguments, see Headrick 1981 and Headrick 1988). As in the case of Burma, the British empire connected the country to its other Asian colonies and beyond, making an imperial web by steamboats, locomotives, and later undersea cables. Regarding Burma, what local people experienced within this modern web and how they understood and responded to the rapidly changing reality have been analyzed in terms of colonial encounters (Thant Min-U 2001, Charney 2006).

The initial moment when locals encountered such new technology was worth exploring because it captures the very instant how different worldviews and ways of thinking met. Michael Charney, in Powerful Learning, features one experience of a Burmese colonial officer who depicted the new technology with his own words in 1835 (Charney 2006, pp.146-7). Shwe Htun kept a journal during his trip to Calcutta from Dawei as an attendant with the Commissioner of the Tenasserim Province. He recorded his bewilderment with an electric machine, calling it as ‘မိုဃ်းကြိုးစက် (thunder-bolt machine).’ After having had an electrical shock experience with a finger dipped in water where an electric machine was placed, he wrote that “if there is a bigger thunder-bolt machine, it will burn up the whole town.”[1] While Charney identifies this account as one of the earliest indigenous experiences of modern technology that later became the seedbed to transform the knowledge landscape among the Burmese literati (Charney 2006, p.148), Shwe Htun’s metaphor of electricity as a natural phenomenon, something beyond human control, indicates some discordance between the Western way of scientific knowledge and locals’ interpretation. A similar point will be articulated in Karen Baptists’ accounts.

Of interest, Shwe Htun’s case also exemplifies locals’ initial familiarization with modern printing, as his journal was published as a print book. Yet, it will be too simplified to say that the British colonial authority was the only provider of such new experiences. Newly converted Baptists in Taninthayi started to have similar experiences as Shwe Htun did. By introducing the Karen Baptists’ accounts, this essay shows an example of multiple networks transcending colonial boundaries and various interpretations that locals of Burma developed about the rapidly changing world.

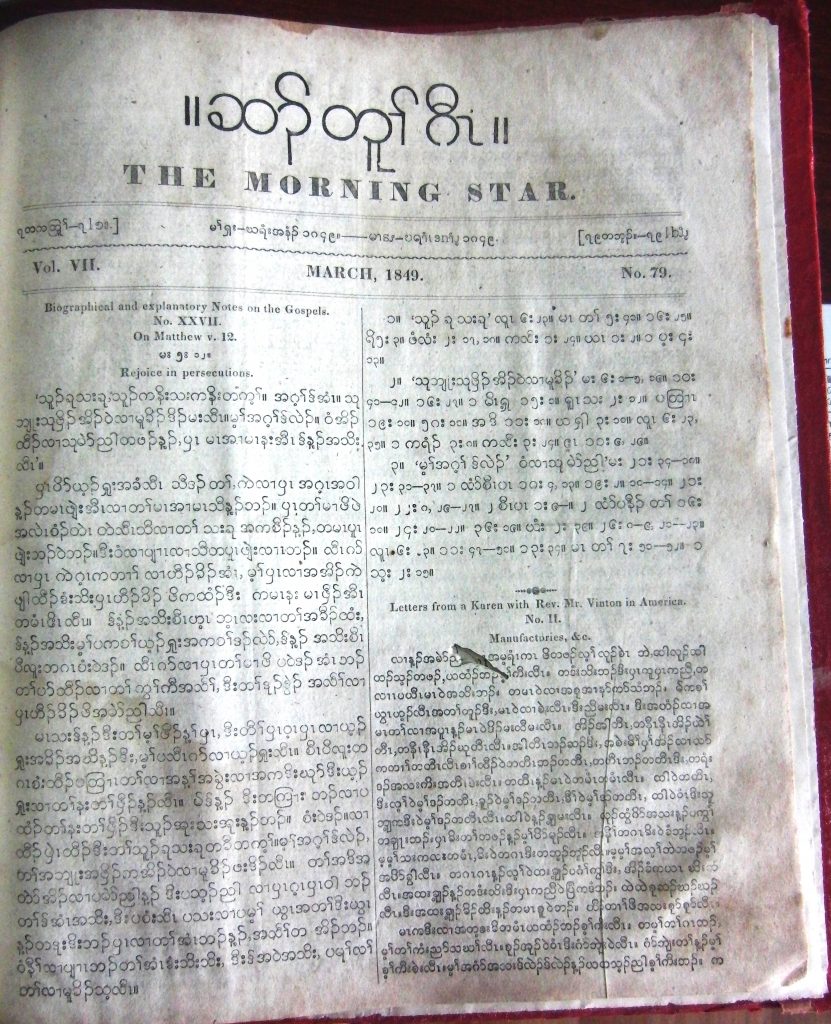

Karen Baptists’ first-hand accounts on their journey to the U.S. can be found in the Sgaw Karen[2] written newspaper Hsa Too Gaw (ဆၣ်တူၢ်ဂီၤ), known in English as The Morning Star. Karen-speaking people started showing interest in the American Baptist mission in the late 1820s, and Karen conversion swiftly increased thereafter. The evangelical appeal was seemingly more successful among the Karen who worshipped ancestral spirits than those who followed Buddhism. In the early 1830s, American missionaries decided to devise Karen characters and the Sgaw Karen writing system. Only a few Karen converts could use the missionary-made Karen orthography initially. However, by the time of the first publication of Hsa Too Gaw in 1842, at least dozens of Karen Baptists had already learned it and regularly wrote letters. Their writings from the 1840s are difficult to access. However, I luckily encountered one set of copies, privately stored by a Sgaw Karen elder living in Kyeemyintdaing, Yangon.[3] Some issues are missing, and many pages are almost unreadable due to huge moth holes, but this set seems the most complete set of the issues of the 1840s.[4] These copies let us trace the first-hand experiences back in the mid-nineteenth century to learn how locals of Burma tried to make sense of the transforming reality through bewilderment.

Our first storyteller is Ko Ler. He sailed with the American missionary Justus Vinton, as Vinton had to return to his home country in 1848 to recover from illness. Boarding the Ocean Queen, the party took a voyage via the Cape of Hope (Baptist Missionary Magazine 1848, p.93). Vinton, Ko Ler, and another Burmese convert named Myat Aye reached New York in March of 1848 (Ibid., p.151). The exact duration of their stay remains unknown, but the party spent at least two months in New York. They both attended the annual conference of the American Baptist Missionary Union held in May of the same year (Ibid., p.207). Although why these two converts visited the U.S. is unclear, the missionaries’ intention, without a doubt, worked out to prove their success and raise donations by displaying the fruits of their foreign mission to Baptist fellows in their home country.

Ko Ler’s life before his conversion is unknown. Some historical records speculate that he was a native Pwo Karen speaker from the Dawei region. An English manuscript produced by an American missionary in 1963, entitled History of Baptist Work among the Pwo Karens of Burma, mentions a convert who travelled to the U.S. in 1848 as one of the earliest Pwo converts.[5] According to this manuscript, he was Missionary Brayton’s language teacher, assisting with Bible translation, and later became a church pastor in Dohn Yahn.[6] He passed away in July 1893, at the age of 75.[7] Ko Ler’s letter was published as five serialized articles in Hsa Too Gaw in 1849.[8] The five articles must have been initially one long letter, but the editor of the periodical at that time, most likely an American missionary, divided it into five separate articles to publish.

Ko Ler started his letter, dated August 25 1848, by explaining his motive to write it, stating that he wanted to share his own experiences with other Karen fellows in Burma.[9] The first section of his letter summarizes Ko Ler’s impression of people there.

America is good. American people believe in God, read and understand God's words, and therefore he gave them every wisdom. If they wish to get something, they can do anything. They live in cities, and their houses are not the same as those in an Eastern country, Burma...God blessed and enabled them to do many things…If everyone in our country prays for God and devotes one's soul to him, we would be able to live in peace, and God would joyfully give us the same skills as Americans have. [10]

Noting the country’s size and the way of life, both of which were so different from his homeland, Ko Ler considered the piety of Americans as the critical factor in gaining God’s wisdom. He continued his letter explicating what kind of ‘wisdom’ he mentioned above: locomotives.

America is not a tiny country…But it is easy to go back and forth between cities, and it is fast. God gave them wisdom when they wanted to go either water or land. You do not need to go on foot if you go by land. If you go by water, you do not need to use your body. You have steamships for waterways and locomotives for land routes…Locomotives move as follows. It does not move by itself. There is one fire-heated car that is working. Many cars with rooms for people are attached behind it. Each car is not very large. The length is about seven fathoms, and the width is about six cubits. I am not sure how many cars the head car can pull. Steam locomotives weigh a lot and continuously move. If the railroad is in good condition, it runs fifty or sixty miles per hour. If the railroad is rough, it runs thirty or forty miles within an hour. They[locomotives] always move and run between cities fast…It moves as if a bird flies. But no birds can fly as fast as locomotives.[11]

Astonished by its velocity, Ko Ler tried to describe how this object functioned. His illustration of the first car as “one fire-heated car” speaks for his genuine observation. To him, a locomotive seemed indeed burning up because it blew up heated steam as it went by. Interestingly, Ko Ler used Western measurement units to explain the velocity, employing an unfamiliar system to calculate distance. However, he must have been certain that this information was surreal and not compelling enough to make what he described apprehendable to his readers. So he added a figurative description, comparing a locomotive and a bird about the moving speed.

In addition to what Ko Ler wrote, his neologism to describe scientific technology demonstrates its novelty to his eyes. His terminology for a locomotive was lày mày oo (လ့ၣ်မ့ၣ်အူ). While this term is common for railways today, it must have sounded very unusual in the 1840s. Etymologically speaking, lày means “cart”, a loan word from Burmese hlé (လှည်း). Mày oo, another loan word from Burmese meé (မီး), stands for “fire”.[12] This new lexicon indeed reflects how odd it was to see the alien artefact running at a tremendous velocity.

His puzzlement to interpret novel objects did not end with the locomotives. He also wrote about the telegraph, which made him even more confused.

They do something like conversing over irons. We have never seen anything like this. It can be surely said that they do not actually talk to each other. It is somewhat similar to exchanging letters. When we receive letters in hand and send them back, a person delivers them, so they do not arrive quickly. Their letter-like message moves through irons within five to six days, ten to twenty days or one month, and reaches [another place]. This letter flowing over irons is not written by hand. A person who has a message to another person living in another area goes to an operator of irons. The person pays a fee as told. Then, he [the operator] quickly types out the letter. The letter is then delivered to another area. But, the letter he types out is not something others can read. The operator is the only one who can interpret. It is not like a usual letter. He bores holes in a line, as if he does so with a gimlet, and reads them one by one. Another operator decodes and re-writes the letter on paper when the letter reaches the other end of the iron. I do not comprehend this whole matter at all. I understand just as what I have just written.[13]

On the contrary to Ko Ler’s confession that what he was seeing was beyond his understanding, his account is surprisingly precise in terms of the operation order. Nonetheless, this communication system using just lines and dots was mysterious. As Ko Ler said, the telegraph letter was incomprehensible unless one already knew how to decode it. Furthermore, it was inexpressible to see letters transported through iron cables to miles afar places. The whole phenomenon seemed to surpass human capability.

Recalling that Ko Ler characterized industrial technology as the wisdom given by God, his comparison of the entire phenomena to nature hints to us what underlines his way of understanding. To the early Karen converts who embraced spirit worship before their encounter with Christianity, controlling nature was never in the human realm. For example, there were different spirits associated with nature, ‘the lord of water and land,’ ‘the lord of huge stones,’ and ‘lord of paddy’ [16] People consoled and prayed for those spirits to avoid any sorts of calamity. Mindful that the Christian God was often referred to with the Karen term ‘lord,’[17] it was perhaps natural for Ko Ler to relate the American’s wisdom beyond the law of nature that is supposedly in the realm of superhuman beings to the power of God.

The next story is told by Taw Mu, who stepped on the land of the U.S. in 1853. Taw Mu was a Sgaw Karen speaker in Dawei. When he became a Christian is unclear, but his encounter with Christianity must have been in childhood because his mother was already a Baptist in 1834. Previously practising animist beliefs, his mother received Baptism in 1837 and made her children learn the Baptist-made Karen characters and the Bible.[18] Taw Mu worked as a preacher at a small village Gyu, located in the southeast of Beik, in the 1840s.[19] He later became one of the prominent pastors in the region as he represented the Dawei congregation at a missionary meeting.[20]

Taw Mu was in the company of American missionary Cross. He spent a short time in Boston, only fifteen days, leaving there on January 17 1853.[21] Despite his limited time, Taw Mu’s stay was full of encounters with bizarre phenomena.

His journal was divided in two and published separately in Hsa Too Gaw. The first part appeared in the issue of August 1853, entitled “Tau Moo’s Letter,” and the second part in the April 1854 issue. Similar to Ko Ler, Taw Mu explained that he would like to describe the things he witnessed in the U.S. “because they [Americans] utilized much wisdom.”[22] The very first thing he picked up was, again, the railways.

When they [Americans] move…they also make locomotives, which run fast on the land. The railroad is made of iron so that no obstacles would block it when it is running. The iron rails are curbed on both edges so that cars would not roll out from the railroads. With such treatments, the rails go back and forth between two places…One town can be very far, and the rails extend for 1,000 or 1,500 miles. Besides the long length of the railroad, the locomotives are very fast. If a railroad were laid, one would be able to move the long distance between Inwa and Beik, for example, just one and half days. Like this, it is as if people are so close to each other, although they are physically far away.[23]

The locomotives’ speed attracted Taw Mu’s attention very much. Referring to Beik and Inwa, the closest town to his village and the former capital of the Konbaung dynasty, Taw Mu illustrated how far locomotives could travel within a short time. Remembering that most Karen speakers travelled on foot or by small boat in those days, it must have been unbelievable to move over 700 miles within one and a half-days. Readers of this letter may not have comprehended the railroad but must have sensed that something inconceivable was happening in their missionaries’ homeland.

Taw Mu also wrote about the gas lamps, another unprecedented invention of the day, the telegraph system, and specimens. In particular, his description of various specimens is worth exploring.

They [American] thoroughly know everything they can hunt on Earth, such as quadrupeds, birds, snakes, centipedes, and aquatic animals. They put them in a large building and soak them into a kind of medicine to preserve the forms of creatures. Whoever wants to see can come and see. Their appearances, including faces, are not decayed at all. It was as if they were still alive. Brothers, there are more things that I have seen in America…There are many things I cannot explain with words because I have never seen these things before.[24]

Observing a strange way to preserve the physical appearance of the dead creature as if it were still alive, Taw Mu was convinced, just like Ko Ler, that Americans knew the way to break through the law of nature. Taw Mu’s comment that “they thoroughly comprehend everything they can hunt on the earth” testifies to this point.

In the latter part of his letter, Taw Mu shifted his attention to the church activities and people’s life as Baptists. Attending a prayer meeting, He was impressed with the size of the church building, the fact that there was a church in every town, regardless if it was big or small as a village, and the number of people gathering for Sunday’s prayers.[25] After providing the details of church prayers, Taw Mu moved on, depicting city life in Boston.

I came to know that the wise people are living in this town, and I am glad to learn that. Their houses and roads were made elaborately. Their clothes and everything we saw was all elegant and luxurious. We saw these things, and we think this is very good. Brothers, please bring all of our family together and let us start helping each other, like helping cook rice. We may not be able to do big things [right away], but we can plan a small thing and do it ourselves.[26]

Given that Taw Mu made the above description right after explaining the widespread Christian community in Boston, his appraisal of refined housing, the townscape, and people’s outfits could be read as connected to their Christian life. Acknowledging God’s blessing at work in American life, Taw Mu cried out to his Baptist fellows to unite and help each other to achieve a similar life. Helping cook rice is an example of “a small thing,” implying the importance of doing what you can do yourself to reach the larger goal. Similar to Ko Ler, Taw Mu understood the unfamiliar lifestyle in the U.S. in a positive tone and urged his readers for devotion to God so they would be able to receive his grace and own the same knowledge.

As shown with both Ko Ler’s and Taw Mu’s cases, Karen Baptists interpreted scientific technology and its industrial implementation, which seemed incomprehensible and beyond human intelligence to their eyes, as knowledge gifted by the superhuman being. Their detailed explanations of events and vivid words show the multiple ways of interpreting ‘modern knowledge’ in those days. It is unfitting to characterize the above stories solely as colonial modernity because those Karen Baptists’ experiences emerged outside the British colonial web. The network they relied on was prepared by the American Baptist mission. Although the American Protestant missions’ networks and their aims overlapped with the British colonial project in many aspects, the above attests that locals’ experiences cannot always be best understood within the colonial framework. The experiences of the colonized did not happen only in the colonial realm.[27]

The Karen Baptists’ voyages to the U.S. attests to their mobility, questioning a premise that non-Europeans in colonies were passive, static subjects awaiting the arrival of the Western people who brought them modern knowledge. Diverse ideas, thoughts, and experiences were open through various channels. Assessing possible dynamic interactions, including people’s mobility, also requires reconsidering the spatiality in which ‘modern knowledge’ was formed. Scientific knowledge formation in the nineteenth century was not unilateral or exclusively Western, but rather an interactive, shared process (Raina 2013). [28] Locals of Burma were indeed more mobile and less confined within the colonial territory than they once seemed.

Lastly, the Karen Baptists’ interpretation tells us that the modern secular understanding was not the only possible perspective towards scientific technology. To many Euro-American people at that time, scientific advancement functioned as markers of civilization and their superiority. But it was mundane testimony of God’s grace to the eyes of Karen Baptists. Echoing the scholarly argument that knowledge is what has been processed by thought, taking shape based on interpretations of those who witness or learn the information (Burke 2000, Livingston 2005), the Karen Baptists were producing their own knowledge about the new, transforming reality through their lens. In this process, the Christian worldview they recently acquired helped them craft a plausible understanding of the new ‘wisdom’ which seemed to surpass nature and human capacity.

Hitomi Fujimura is a postdoctoral fellow at Osaka University, Japan. She is currently visiting York University in Canada as a postdoctoral fellow. After two years of fieldwork in Myanmar from 2014 to 2016, she obtained her Ph.D in 2019. Her dissertation reconsiders Karen converts’ experiences and roles, particularly Baptist intellectuals, within their mission and political actions. Her research interests include local Baptists’ activities in colonial Burma and the history of Christianity in Myanmar in general.

Like This Article

May 15, 2023

November 25, 2021

September 08, 2021

August 13, 2020

Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Asian Institute 1 Devonshire Place Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3K7, Canada

©TeaCircle All Rights Reserved 2023