Tha Peng Cung examines the reasons for severe deforestation in Chin State.

While State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi inaugurated the Tikir Dam, a hydropower plant in Than Tlang, Chin State, she declared:

I wish to request the Chin people one thing though [sic]. Please, try to refrain from cutting down trees. Because, on my way here in the helicopter, I could see the enormous extent of deforestation in the area… In Kachin State, I saw the lush green forests… I want Chin State’s forests to be the same.

Aung San Suu Kyi, (Global New Light of Myanmar, 21st January 2019).

Her speech raised many questions for me: is wood for cooking fuel a major driving force for deforestation? How many areas of the forest in Chin State have been devastated? What are the main reasons for such an enormous extent of deforestation in Chin State? When did deforestation begin?

I was given an opportunity to answer these questions during my postgraduate research titled “Water Governance in Chin State from Political Ecological Perspective and Integrated Water Resources Management Perspective ” in March and April 2019. By exploring forest management in Chin State from political and ecological perspectives, I found that forest coverage in Chin state had been in decline since British colonisation. As a result, I decided to compare the policies of forest management under British administration and the current administration and seek reasons for deforestation in the region.

I took a journey to Hakha, Capital of Chin State, from Brisbane, Australia, where I was doing my postgraduate study.

Due to steep terrains in Chin State, transportation links are very limited. The infrastructure is inferior, with no fully paved roads, making access difficult. The journey from Yangon to Kalaymyo takes approximately 18-19 hours. The bus from Kalaymyo to Hakha began with a prayer for a safe journey, led by one of the passengers.

Google Maps indicates that the journey is 110 miles and 5 hours and 47 minutes long, but in reality, it took me 7.5 hours on a bumpy road. There were no seat belts. Although the roads were designed for two-way traffic, they were not enough for two cars driving along the road. The driver had to honk forcefully during blind turns and slow down when the bus went within inches of the edge of the road.

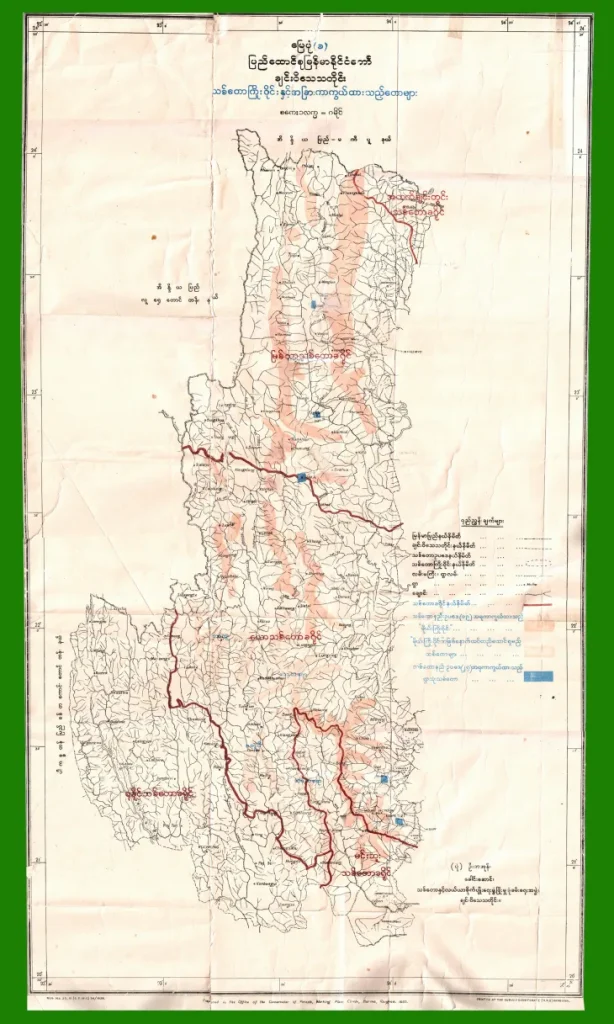

I explored the forest management system in Chin State through a literature review and interviews with local people. I was able to retrieve the data of climatic and reserved forest areas under the British Administration, which are not accessible to the public, from one of my respondents’ private libraries.

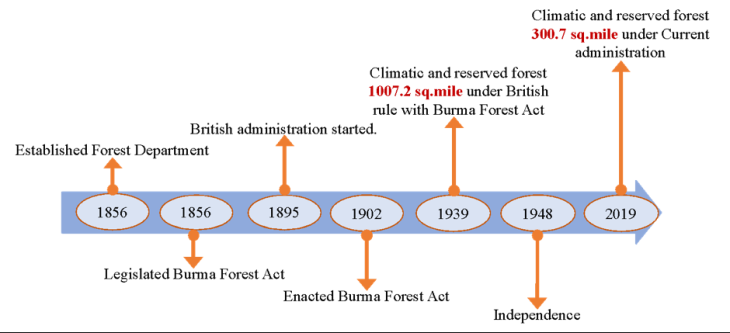

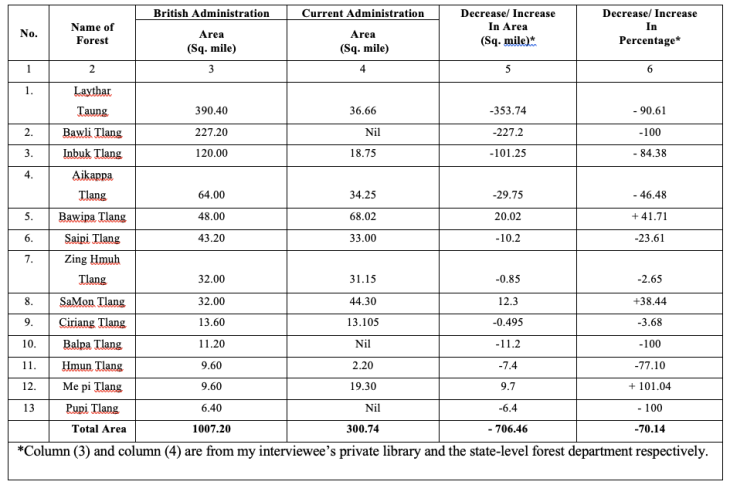

The British Forest Department was established in 1856 and the first Burma Forest Act was legislated in 1881. However, Chinland was an independent domain until 1895, the year in which Chinland came under the British administration. Under the Burma Forest Act of 1902, the climactic forests (မိုးကြိုးဝိုင်း) and reserved forests (သစ်တောကြိုးဝိုင်း) in Chin State were notified in 1939 (see Table 1).

Under the British Administration, forest policies were laid and practiced after gathering data about the climate and forests reserves according to the Burma Forest Act. The Burma Forest Act was then adapted into the local Chinland context as follows:

As a consequence of preserving the forest, the local people enjoyed not only tangible benefits such as timber, food, fodder and shelter, but also intangible benefits such as water storage, soil formation, air purification and a healthy life. According to one of my interviewees, “the monsoonal wind brought regular precipitation, and there were seasonal flowing creeks and brooks across the state. Thanks to the British administration for preserving the forests” (independent expert, 22 March 2019).

I approached the Chin State Forest Department in Hakha to get data about current forest management policies. There, one person suggested that I go to the Chin State Government Office to get forest data that had already been approved. However, when I got there, the Chin State Government Office referred me back to the Forest Department in order to get the most up to date data.

Hence, there are some data variations in regard to the current situation of climatic and reserved forests areas as a result of poor data keeping practice. According to the collected data, I compared the situation of forest coverage under British rule and current administration (see Table 1 below).

Unfortunately, it is very difficult to verify why the areas of three reserved forests, namely, Bawli Tlang, Balpa Tlang and Pupi Tlang are “nil” in the Department’s documentation. Still, my data shows that the deforestation in Chin State under the current administration is substantial. Table 1 shows that, on average, more than 70% of the forest areas have been devastated between 1939 and 2019.

World War II was one of the main reasons of substantial forest deterioration, caused by bombing, gunpowder and transporting the troops through the reserve forests (interview, independent expert, March 22, 2019). Yet, deforestation has continued due to poor management by the administration of Burmese governments since independence. As my interviewee put it, the “Burmese Union administration was weak after the liberation of the country from British rule in 1948.” (interview, independent expert, March 22, 2019).

For instance, Dongva village (36 miles from Hakha), was established by the British as a forest village. Forest villages were instituted under British forest policy, which states that a forest village with a maximum of twenty households would be established in each reserved forest to assist forest rangers. However, there are currently more than 70 households in the village. As a consequence of weak administration, the deforestation rate was exponential and wildlife preservation was fragile.

When questioning the reasons for such substantial deforestation, one official from Forest Department shared: “I am not sure about other things but what I can say is that Jatropha plantation and green tea plantation projects imposed by the military regime might have had an impact to some extent.”

On 5 December 2005, on television, Senior General Than Shwe stated that “States and Divisions are to put 500,000 acres under the physic nut plants (Jatropha) each within three years, totaling seven million acres during the period.” The Senior General’s words set off orders commending every citizen to take up jatropha planting as “a national duty.” The uniform distribution of 500,000 acres in every state and division is not practical in terms of the total land area available, the population, and the climate or soil condition of each state. In Chin State, in order to meet the quotas under General Than Shwe’s plan, each Chin person would have to plant more than 1.25 acres, since the population of the Chin State is less than 400,000.

Besides Jatropha, Chin State suffered from another government project called, “Chin State as Tea state”. During a visit to Chin State in 1998, the second chief of the Burmese junta General Maung Aye ordered that Chin state would become a tea state. In accordance with his declaration, the Chin State agriculture department started a tea plantation movement in 1999. The first report from the 2008 budget year report, total tea plantation areas is 19,433 acres, and of these, trees in 9,977 acres have lived.

In other words, the imposition of the central policies to Chin State without any consideration of the local context and social life is a reason for forest decline, apart from the weak administration of the Myanmar/Burma government.

Furthermore, 70% of my interviewees out of 31 respondents perceived that the practice of shifting cultivation which covers approximately 80% of the total land area serves as another factor to cause deforestation in Chin State. In fact, the stated ‘80% of the land area’ is just speculation as even the Department of Agricultural Land Management Statistics (DALMS) does not know the exact figures.

As an official from DALMS stated: “he department has a very limited capacity in terms of human resource, technical and financial to take the actual record data of shifting cultivation due to the topography in Chin State” (interview, government official, March 10, 2019).

The majority in Chin State are still using woods and charcoal as cooking fuel. This is another aspect to be considered for deforestation although there is no available data. However, it is assumed that a statewide electrical power supply can substitute the use of woods and charcoal for cooking.

As H.E. Daw Aung San Su Kyi mentioned, it is undeniable that deforestation in Chin State is extensive and substantial due to imposition of central power by force. Comparing the situation under British administration in 1939, it is revealed that more than 70% of the climatic and reserved forest in Chin State has been devastated after independence.

It is obvious that the climatic and reserved forests have been decreasing after the liberation of the country. I conclude that the reasons behind this extensive deforestation are as follows:

All in all, 70 % of my interviewees thought that shifting cultivation is a driving force for deforestation in the study area. However, this paper claims that the imposition of the central power (such as jatropha and tea plantation) without considering the local context and social life is more severe than the practice of shifting cultivation, a traditional way of livelihood. Therefore, legislative effectiveness and enforcement in line with local context, social life and traditional way of life is urgently needed.

The forest conservation and reforestation plan should be prioritized from the national level, and should emphasize local needs. The government should promote not only capacity building of the local authorized organizations but also community based public education plans. Conducting research on the kinds of agricultural technologies and policies that fit with the local situation is highly recommended for further studies.

Hope for the Ever-Green Chin State.

Tha Peng Cung is an emerging young water professional from Myanmar. He is currently working as a staff officer for the Irrigation and Water Utilization Management Department, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation. Ethnically, he is Chin and graduated from the Technological University (Kalay) with a Civil Engineering Degree. Further, he did his Masters of Integrated Water Management (MIWM), run by the International Water Center and hosted by Griffith University.

Like This Article

April 09, 2024

February 23, 2024

December 27, 2023