In Part Two of a three-part series, Bobby Anderson examines the case of Tonzang and its exception to conditions for opium-funded insurgencies in Myanmar, as outlined in Part One.

This three-part series discusses historical and contemporary insurgency and opium cultivation in Myanmar, and the conditions in which the drug trade supports territorial control, either for the state or its rebels. It focuses particularly on northern Chin state—an outlier in that a thriving opium trade there does not finance an insurgency.

In Part One, I described the factors that lend to the durability of insurgency in Myanmar over time: geography, resources, and people. I also explained the interplay of drugs and insurgency across decades. Part Two looks at where Northern Chin, and Tonzang in particular, fits into this triage of crime and insurgency.

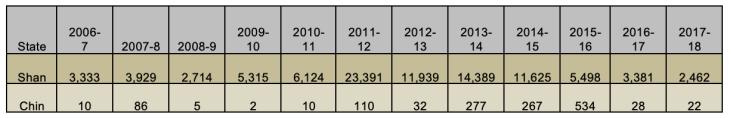

Simply put, it doesn’t. Tonzang contains all the elements for durable insurgency, but without the durable insurgency. Tonzang might be characterized as a forgotten township in a forgotten state. This says more about our short attention spans than the actual forgetfulness of such places as we overlook Tonzang and innumerable other corners of the Union in favor of place-names like Shan and Kachin, lands soaked in stereotypes of blood and shadow like hardtack in water.

Further to the west, however, Tonzang contains the advantage of geography in spades. To the west of Kalay (the nearest town to Chin State with an airport), the road into Western Tonzang rises in unstable and landslide-riven switchbacks, only stabilizing when it reaches the tops of mountain ridges. The road passes Tedim before plunging thousands of feet downward and briefly following the Manipur river, again rising in switchbacks to the township capital, after which it drops to cross the Manipur river one last time before rising, in ever more switchbacks, over the hills toward Chikha.

Here swiddening Chin families build new villages on outcroppings where water is scarce, not in the interests of defense, but because a 3G signal is plentiful. We humans are really just a less-majestic species of crow.

The Kukis have yet to realize self-rule, the postcolonial mantra. We continue to be victims of sub-colonial imperialism...

PS Haokip | Zale’n-gam: The Kuki Nation. Zale’ngam: Kuki National Organization, 2008

In May of 2015, Public Radio International (PRI) cast doubt upon reported eradication, quoting Tonzang town council member Cin Tung Mang:

“[In 2013] there were people here from government who were supposed to eradicate opium. They only destroyed a few nearby fields that are easy to get to. They said they eradicated 60 percent of all the fields, but that’s not true.”

PRI reported it was closer to 20 percent. In that article, USDP Tonzang chair Hen Thang claimed that opium farmers were taxed by local officials in exchange for protection, and that “last time the police went out to eradicate, they took bribes from the farmers to ignore their fields.”

In early 2018, local officials in Tonzang told me that 202.5 ha (500 acres) had been eradicated the previous year. Who is to be believed? UNODC records are likely less accurate than township sources. But at present, township officials don’t know how many ha are under cultivation. One can purchase high-resolution satellite photos and undertake a manual count, but even that won’t reveal the extent, because the steeper the cultivated hillside, the harder it is to see from space. Township officials and locals only know that it’s happening, and likely with the collusion of and taxation by select local authorities, civilian and military—a protection racket of the classic sort described by Charles Tilly or Diego Gambetta.

An insurgency must lay claim to lands and peoples claimed by the state. It has to be noticed. If an armed group claims no square footage, it implicitly places itself in a subservient position vis-a-vis the sovereign that claims the territory it exists within; instead of offering protection, it accepts, and pays for, protection.

When this is coupled with interviewees across Tonzang uniformly asserting that opium here is trafficked into Northeastern India through a multitude of official and unofficial border crossings, one begins to see less an alien insurgent presence and more the people who have always been here, and who have always just regarded the borders as inconveniences—for hunting, visiting family, smuggling, and demarcating their own territories in a manner that transcends those of states.

Tonzang’s stereotype is Shan-lite. Lacking warlords and child soldiers, but still a place remote and primitive, lacking all semblance of the state bar corrupt security forces, with opium farmers and smokers everywhere.

This, however, is not the reality of this township.

In Part Three of the series, I describe the opium growing villages I’ve visited in Tonzang, and how they differ from the stereotypes we often hold about such places. I describe the difficult positions of farming communities who were once self-reliant but are more and more integrated, for better or worse, into cash-based markets. This is followed by the conclusion of this series, which considers opium as a proxy indicator of coerced integration of non-market-reliant peoples into markets, from resource security to cash insecurity.

Bobby Anderson (gletkin@gmail.com) is a Myanmar-based Research Associate at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. He thanks Jasnea Sarma for her comments on an earlier draft.

Notes

Like This Article

March 06, 2024

February 23, 2024

February 22, 2024