Julian (pseudonym) outlines China’s geostrategic calculations and ambitions in Myanmar.

Since the coup, the majority of anti-coup protesters and the general public in Myanmar have suspected that China (and Russia) gave implicit consent to the military to stage a coup, which China has since denied. Some have cited the cargo flights between Kunming and Yangon, which was claimed by both sides as regular flights for ‘seafood’ cargo. Such events have fueled speculation that China is supporting the junta with equipment and experts.

Subsequent events have shifted public perceptions of China in a negative direction, resulting in growing anti-China sentiment in the country. For example, protests near the Chinese Embassy in Myanmar were frequent in the early days of protests before the brutal crackdown by the military. Amid growing tensions, there have been threats to burn down Chinese oil pipelines, a reflection of public anger and perception that China is backing the military. Tensions escalated when some of the Chinese investments in Hlaing Thar Yar, the manufacturing district of Yangon, were burnt down on 14th March. The Chinese Embassy issued a statement on the same day, demanding that authorities take effective measures to stop violence and to punish the perpetrators (although it is unclear who the perpetrators were), but the statement does not mention the brutal military crackdowns and mass civilian killings that occurred. Furthermore, despite the consensus reached and explicated in the Press Statements in 4th February and 1st April, and the Presidential Statement in 10th March by all 15 United Nations Security Council (UNSC) members to condemn the military’s actions, to urge the military to immediately cease the violence, release all political prisoners and return to democracy, Chinese diplomats offered ‘watered down’ statements, urging softened tones of the condemnations of the violence in Myanmar; for instance, blocking the use of the phrase ‘readiness to consider further steps’ in reference to international sanctions, and softening the word ‘killings’ into ‘deaths’.

China’s responses to Myanmar’s coup are somewhat complex. To understand China’s actions thus far, it is beneficial to widen the scope of analysis and consider China’s geopolitical interest and calculations in the country and its motivations for establishing regional and global hegemony, particularly in Myanmar. This essay will look at China’s stance on the geopolitics of the region, it’s foreign policy, and its links to Myanmar’s current crisis: First, what are China’s geopolitical ambitions in Myanmar? Second, what is China’s non-interference foreign policy, and some of its recent controversies? Finally, how are these related to Myanmar’s ongoing crisis?

China has important trade and investment relationships with Myanmar, especially in providing food and energy security for the landlocked Yunnan province in southwest China. For instance, Myanmar-China pipelines linking the deep-sea port of Kyaukphyu to Yunnan provides essential resources for Yunnan’s energy security. In addition, Myanmar is an integral part of China’s Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI), China’s most ambitious infrastructure project in the 21st century. Most BRI projects in Myanmar were agreed to and signed during President Xi’s visit to the country in 2020. Myanmar is also geographically pivotal in BRI projects, as they link China’s southwestern interior to the Indian Ocean.

The Indian Ocean has its own geopolitical importance to China. The Indian Ocean is vital for China’s geopolitics as part of its ‘Two-Ocean’ strategy. The strategy, in its simplest terms, is to gain more political influence over both the Pacific and the Indian Oceans to balance the power of its geopolitical counterparts in the Asia-Pacific Region, and to expand China’s geopolitical power regionally and globally. In the Pacific Ocean, China’s major geopolitical threats are Japan, South Korea, the naval bases of the USA, Taiwan, and Australia. The Indian Ocean serves China’s ambitions for growing influence in the far seas through its vision for expanded commercial and logistics interests.

The Indian Ocean also serves China’s geopolitical objective of ‘containing’ India, one of China’s largest geopolitical threats in the region. China’s aim to encircle India with Chinese mega infrastructure, marine bases and facilities, both militarily and commercially, is known as the ‘String of Pearls’ strategy. Some of the biggest projects under the strategy include the Gwadar Port Project in Balūchistān province of Pakistan as part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the Hambantota Port Project in Sri Lanka, and the Kyaukphyu Port Project in Rakhine state, Myanmar. It is believed that China has an overall geopolitical aim of establishing global dominance and hegemony in West Pacific as well as in Eurasia, Africa, and the Indian Ocean, as reflected in the Foreign Policy article by U.S. National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan.

As Myanmar is one of the two countries bordering China with direct access to the Indian Ocean, it is a key country where China’s two crucial geopolitical strategies––the ‘Two-Ocean’ and the ‘String of Pearls’ strategies––intersect. As China’s projects in Myanmar are economically and geopolitically significant, China’s fear is that further escalation of the conflict in the country will jeopardize the successful implementation of the signed BRI projects in the country, especially the Kyaukphyu Deep Sea Port, which is central to China’s massive economic and geopolitical interests, and the two crucial strategies mentioned above. Therefore, in the eyes of China, prolonged conflicts between the military, Ethnic Armed Conflicts (EAOs) and the public in Myanmar do little to further China’s geopolitical interests. China’s actions are thus consistently aimed at reducing the tensions and resolving the conflict among different stakeholders in Myanmar, which I discuss in the below sections.

Since the coup, Western democracies––the US, UK, and the EU––have been vocal in condemning the coup and advocating the return to power of the members of parliament elected in the 2020 General Elections. Britain was the first country to request a UNSC meeting in response to Myanmar’s military coup. Consequently, Western nations have continuously pressured the junta through multilateral diplomatic channels and targeted sanctions of top military generals as well as some military-related business enterprises. Such Western sanctions were generally opposed by China.

Chinese foreign policy centers around the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, which include non-interference, non-aggression, peaceful coexistence, and respect for other country’s sovereignty in the international arena, as set out by Zhou Enlai at the Bandung Conference in 1955. Generally speaking, China’s foreign policy adheres to the principle of non-interference in the internal or domestic affairs of another country, and urges the international community to respect the territorial integrity and sovereignty of a nation.

However, as China emerges as a superpower with growing global dominance and geopolitical ambitions in international politics, the country has faced difficulties in adhering to its non-interference foreign policy, as set out during the Cold War era. As its economic and geopolitical interests now span the world, China intervenes only when a nation’s internal conflicts have prolonged and deteriorating effects on its ambitions within that country. To that end, China rebrands its non-interference principle as consultative intervention when necessary, arguing that its role is to apply the policy of non-interference by framing its engagement through consultation with the sovereign body, rather than forceful intervention. China’s non-interference is under scrutiny due to its willingness to protect its economic interests through military means. As China’s status has grown in recent years, it faces a new dilemma between non-interference and protection of its national geopolitical interests in its foreign policy. For the first time in history, China broke with its non-interference policy when it sent peacekeeping combat troops to Mali in 2013.

The abovementioned rationale and case shows the disparity in China’s non-interference foreign policy and its practice. China’s recent foreign policy considerations are not only limited to its prescribed objectives, but also by its growing economic and geopolitical interests and a concerted effort to protect its role in the international community.

5 Minutes To Read

October 10, 2018

15 Minutes To Read

January 31, 2019

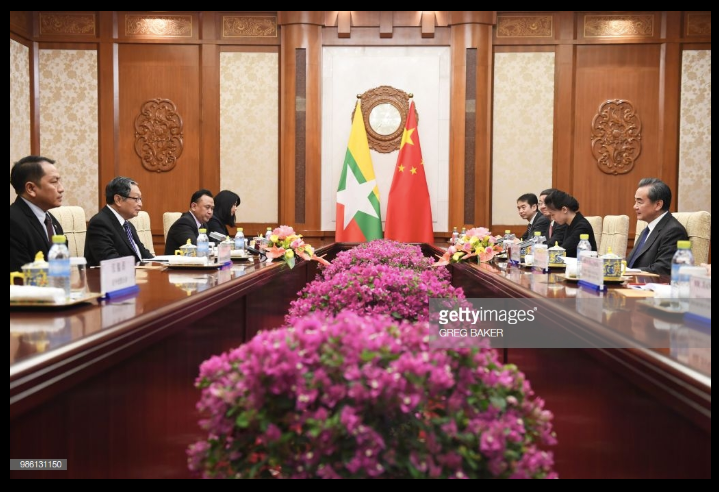

In the case of Myanmar’s coup, Chinese media has been reluctant to use the term ‘coup’, describing it instead as a major cabinet reshuffle. In Beijing’s response in February, China urged different stakeholders to resolve the differences in Myanmar through dialogue, though it continues to be hesitant in explicitly condemning the coup. As the tensions have escalated in the country, China has shown support toward ASEAN efforts in resolving Myanmar’s political crisis. From March 31 to April 2, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi met with representatives of four ASEAN members––Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines (the countries most vocal about Myanmar’s crisis)––to discuss the issue. Although ASEAN decision-making is based on consensus, these nations could help facilitate backdoor diplomacy through negotiations within ASEAN. Furthermore, China’s meeting with these ASEAN nations shows its willingness to deescalate the tensions in Myanmar and to support ASEAN’s role in facilitating Myanmar’s crisis. This also shows China’s strategic diplomacy in dealing with the conflict. Its willingness to deescalate the tensions, however, is not out of concern for the protestors or alarm about the junta’s brutality, but likely because of its interest to protect its geopolitical and economic assets in Myanmar. In addition, such acts makes it clear that China aims to assert its geopolitical influence in the region by positioning themselves as a key mediator for resolving conflicts in the region.

China’s reluctance to call out the military coup in Myanmar alongside their subsequent support for the role of ASEAN in resolving the conflict can be seen as part of diplomatic efforts to balance its geopolitical interests and non-interference foreign policy. As China needs political stability in Myanmar to ensure the success of its investments and BRI projects, China is practicing ‘soft interference’ through dialogue and mediation, thereby relying on regional organizations like ASEAN to mediate in times of severe challenges to regional peace and stability, as they have done with Myanmar’s coup. China has also tried to minimize Western interference in Myanmar by rejecting the use of sanctions and softening the tones of the statements in the UNSC. However, as there has been a history of Chinese interference when its interests are severely challenged, whether it will further intervene in Myanmar remains a question.

There are two conflicting perspectives on whether or not China has bet on the military. Betting, in this case, means the country believes that the Myanmar military will succeed in consolidating power and hence, will provide the needed support. As a result, the country cultivates a closer relationship with the Myanmar military in the long run.

One perspective is that China is the biggest loser in Myanmar’s coup. Myanmar’s coup has produced political instability and uncertainty, which is detrimental for China since it will only delay the implementation of its various BRI infrastructure projects and China’s ambitions for wider geopolitical influence. Furthermore, China is concerned by the disruption of existing trade relations and investments, such as the Chinese gas pipelines in Myanmar that serve the energy demands of Yunnan Province. Clashes and fighting along the Myanmar-China border between the military and Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and other EAO alliances, as well as the likelihood of further escalation, will only produce massive humanitarian, political and economic consequences in the border area.

Another parallel perspective that favors China’s bet on the Myanmar military is its demands for border security, regional peace, stability, and efforts to strengthen its relations with Russia. In Jason Tower’s article, he mentions a Chinese think-tank’s claim that the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) and the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH) is funded by the Western NGOs and others in the West, painting a partial picture of how the Chinese perceive the CDM, CRPH and the overall anti-coup movement in Myanmar.

Unpacking the historical relationship between China and Myanmar’s military leadership will also help us understand whether China has bet on the military. China’s relations with the military were jeopardized in the previous decades (1988-2011) when Myanmar was under military rule. Despite the fact that Myanmar’s generals relied on China’s political and economic support during their isolation, and China handed its previous veto in 2007, the generals have always feared the domination by China, and have resorted to any attempt to counterbalance China by strengthening their cooperation with other countries such as India, Russia, Thailand, Singapore, North Korea and Malaysia.

After Myanmar’s top-down democratic transition and the 2010 General Election, the USDP government, led by President Thein Sein who was the former military general, suspended China’s ambitious Myitsone Dam Project in 2011. The USDP government established and renewed diplomatic relations with the West during its administration in 2011-2015 through a new foreign policy objective of reintegrating Myanmar into the international community. It is the USDP government that has attempted and succeeded in engaging with the Western democracies in international relations, inviting Western investments in the economic realm as well as welcoming Western NGOs, especially in the fields of human development and humanitarian assistance. For these reasons, China may harbor mistrust towards the Myanmar generals.

In addition, recall that Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Myanmar in January 2021 and met with President Win Myint and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi two months after the landslide victory by NLD in the General Elections. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China states that Wang Yi’s visit demonstrated “China’s anticipation and support for the successful formation of Myanmar’s new government as well as Myanmar’s efforts to realize national rejuvenation and lasting peace and stability along the development path independently chosen by the country and in the long-term interests of the people of Myanmar.” The statement showed China’s support for the NLD victory and its upcoming formation of a new government by calling the Hluttaw in February 2021. In addition, during the NLD administration, the government sought closer ties with China, especially since the Rohingya crisis created deep divisions between Myanmar and the Western governments. During the past five years, Myanmar-China relations have improved not only between the governments, but between the two parties, the NLD and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

If China has had a history of controversial relations with the military, and a relatively ‘better’ relationship with the NLD, why do some scholars and the public believe that China has bet on the military? China’s responses to Myanmar’s coup focus more on its own geopolitical ambitions and less on the regime of the neighboring country. China’s geopolitical objectives in Myanmar are to ‘encircle’ India, and to gain access to the Indian Ocean through its BRI infrastructure projects as part of wider ambitions for global dominance. Therefore, China needs a stable Myanmar on the one hand, and on the other, to deal with the regime in power––legitimate or otherwise––in order to fulfill their geopolitical ambitions in Myanmar in the long run. China is making careful and calculated moves to protect their geopolitical interests in Myanmar, while relying on its policy of non-interference to limit Western intervention in Myanmar’s internal conflict.

(Featured image from Flickr Creative Commons)

Julian (pseudonym) is an independent political analyst who studied politics and geopolitics.

Like This Article