Han Htoo Khant Paing and Richard Roewer analyze how political parties have changed their campaign strategies to prepare for the 2020 election.

On the 3rd of November, voters in 13 constituencies across Myanmar headed to the polls to choose their elected representatives. This was the second by-election since the National League for Democracy (NLD) won a landslide victory in the 2015 general elections. Since that hopeful juncture, the NLD has stayed behind the expectations of voters, while the West’s will to intensify economic cooperation with the country has diminished due to the government’s handling of the Rakhine crisis and the slow progress with legislation that secures foreign investment. Voters in ethnic minority areas have also largely lost hope in the NLD – once seen as a partner – in the face of a deadlocked national reconciliation process.

In the light of these developments, some observers have called the by-election a litmus test of the strength of political parties ahead of the 2020 general elections. Suggesting as much might be a little far-fetched. Even during the by-elections, members of political parties were quick to point out that campaigning resources were limited and that they were “saving strength” for 2020. Moreover, voter turnout is traditionally low during by-elections. But, as we argue here, the contending parties have been testing the water. They have been trying new narratives and are changing election strategies. The recent by-election is thus a useful barometer for the developments that we may see in Myanmar’s political party landscape in the next two years and can help predict the key dynamics in the campaigns leading up to the 2020 election.

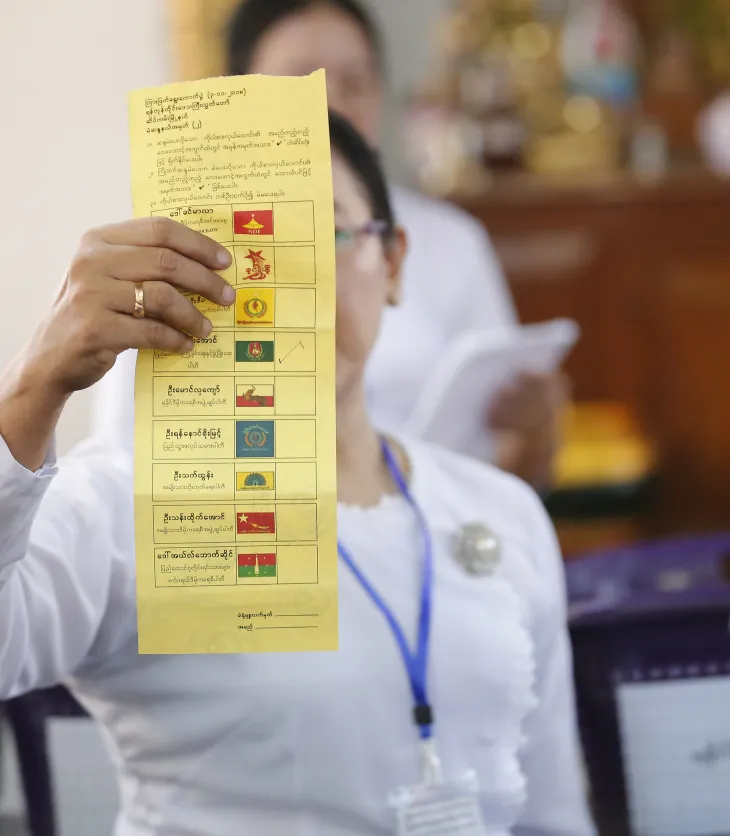

The official results were announced by the Union Election Commission (UEC) on the 4th of November, one day after the election. The NLD won in 7 constituencies, the USDP in 3, the Chin League for Democracy (CLD) secured a victory in 1 constituency as did the Shan National League for Democracy (SNLD) and individual candidate Tin Maung Win. The Human Rights Commission and other monitoring organizations, such as the People’s Alliance for Credible Elections (PACE) released findings stating that no anomalies were found. The results were quite unsatisfactory for the NLD since it had previously won in 11 of 13 constituencies that were up for grabs in 2015. Of the 6 constituencies it failed to win this time around, 5 are ethnic minority areas. Tamu, in the Sagaing Division, is the home to many Chin. Yet, the NLD was defeated by the USDP in that constituency. Dr. Myo Nyunt, the NLD’s spokesperson, commented on the result, saying that the party’s failure to succeed in the area was due to the widespread perception of the NLD as a Bamar party that relates too little to ethnic people. However, it had won in 3 of the constituencies in the 2015 election. In an interview with The Irrawaddy, when asked about the failure to deliver the promises made prior to the 2015 election, the spokesperson said that these goals cannot be achieved only by efforts of the NLD. Still, at some point in the same interview, he emphasized the need for a forceful unitary voice to amend the constitution and implement federalism, which were the party’s major promises.

USDP spokesperson Dr. Nanda Hla Myint, said that the party appreciated the NLD’s effective use of the in-office status in campaigning. Kanpetlet, a Chin ethnic region in which the USDP enjoyed strong support, was won by the NLD. He said the situation changed because of State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi’s visit to the region during the campaign period. During her visit, she promised to promote a village tract to township status. Since the USDP expected to win in half of the constituencies it contested in, it was not satisfied with the result. However, Nanda Hla Myint argued that the result proved that people had learned about the performance of the NLD government in comparison with the prior USDP administration, referring to the diminishing success rate of the NLD in 2017 and 2018 by-elections. The USDP won in the Seikkan constituency in Yangon which has only about 1500 eligible voters, who are mostly civil servants and their families. Back in 2015, the NLD candidate won the Seikkan seat in the Yangon region parliament. Although the NLD candidate tried hard to win votes, including making promises for better civil servant housing and canvassing with celebrities, he reported that his campaign received negative responses from the community such as “no red” banners and the throwing of water and litter at the campaign group.

SNLD candidate Sai Oakka won in the Lai-Hka constituency where the party has a firm hold through the support of the Shan majority. In an interview after the election, he restated his campaign pledge to promote in-school democracy and improve the teaching of the Shan language and literature. Another victory to note is the victory of the individual candidate Tin Maung Win in the Rathedaung constituency. He is the son of Dr. Aye Maung, former chairman of the Arakan National Party (ANP). After the party split in 2017, he was expelled and placed under arrest with the charge of treason. Dr. Aye Maung told the media before the election that he would quit Rakhine politics if his son were to lose the election. Yet, even before the election victory of Tin Maung Win, who won an absolute majority with 82%, Dr. Aye Maung had been trying to form a new party together with his son, the Arakan Front Party. The proposal to form the party was approved by the UEC a few weeks before the by-election.

Although the NLD faced losses in most ethnic areas, the party was able to maintain its grip in Kanpetlet and was able to keep the position of Shan Ethnic Minister of Mandalay Region. The minister-elect Sai Aung Pann Sai reaffirmed his promises to promote Shan literature and establish community centers for Shan as well as other ethnic people in the Mandalay Region. One of the losers was Nan Htwe Hmone, a prominent member of the SNLD. U Sai Lait, the spokesperson of the SNLD, argued that the voter list had contained a lot of errors due to the failed immigration regulation. According to him, many urban voters who were named Shan were not actually Shan. Apart from the SNLD, only the Chin League for Democracy (CLD) was able to secure a win (in Matupi).

According to media reports, the turnout was as low as expected. Out of more than 52,000 eligible voters, only 30,478 voted in Rathedaung. The situation was even worse in Kachin State, with less than one third of eligible voters (about 69,000 in over 230,000) casting their vote in the election.

Table 1: 2018 By-Election Results

| Hluttaw | Constituencies | Before | After |

| Amyotha Hluttaw | Kachin State constituency 2 | NLD | USDP |

| Pyithu Hluttaw | Yangon Region Tamwe | NLD | NLD |

Chin State Kanpetlet | NLD | NLD | |

Shan State Lai-Hka | SNLD | SNLD | |

Mandalay Region Myingyan | NLD | NLD | |

| State and Regional Hluttaws | Magway Region Minbu 2 | NLD | NLD |

Sagaing Region Tamu 2 | NLD | USDP | |

Bago Region Oktwin 2 | NLD | NLD | |

Mandalay Region Thabeikkyin 1 | NLD | NLD | |

Yangon Region Seikkan 2 | NLD | USDP | |

Chin State Matupi 1 | NLD | CLD | |

Rakhine State Rathedaung 2 | ANP | Individual | |

Mandalay Region Shan Ethnic Affair Minister | NLD | NLD |

The National League for Democracy was the only party competing in all vacant constituencies. It did so with a new tone, having changed its motto from “Time to Change” (2015) to “Together with the People” (2017) and finally, the current “Collective Strength.” Indeed, unity seems to have become a cornerstone of the NLD’s new narrative. The party’s spokesperson, Dr. Myo Nyunt, did not fail to reiterate that the party wishes to represent the whole union, adding that the NLD is not only working for the Bamar, but all ethnicities. He supported this claim with another, namely that the party gave priority to ethnic people when considering candidates. Yet, his comments drew criticism from other parties. Sai Nyunt Lwin, the General Secretary of the Shan National League for Democracy (SNLD) was quick to point out that Dr. Myo Nyunt had made a similar appeal to ethnic minority voters in 2017 in an effort to sway them to vote for the NLD, but pointed out that it was conceptually wrong to urge constituents to vote for a single party to increase ethnic representation and support the formation of a federal state.

The NLD itself is aware that winning seats in certain ethnic minority constituencies is an uphill battle. Dr. Zaw Myint Maung, the vice chairman of the party, told the media during the campaign period that the NLD’s chances to win in the Rathedaung and Lai-Hka constituencies (in Rakhine and Shan State respectively) were quite low. Notably, among all vacant seats in the 2018 by-election, these were the only constituencies in which the NLD did not win in the 2015 election. The choice to compete for seats in all vacant constituencies, specifically in ethnic minority townships where the party itself knows that it is likely setting its candidates up for failure, is a strategic decision that stems from the party’s narrative of “collective strength.” The party’s leadership seems to believe that unity does not so much lie in cooperation with other parties, but rather in continuing to cultivate an image of a “people’s party” that represents people across lines of ethnicity. In doing so, the party seems stuck in the pre-2015 past when this image was more popular amidst the euphoria of the changes the party promised.

The USDP has never hesitated to use the failures of the NLD to its advantage, taking every opportunity to remind the NLD of the things it had promised in 2015 while never failing to remind people of the successes the USDP had achieved following the 2010 general election. Unsurprisingly, the party’s campaign narrative was built around nationalism, patriotism and sovereignty. The party did not tire of framing the atrocities committed against the Rohingya as acts of ensuring national security, an approach that likely spoke to many voters. Moreover, the USDP portrayed itself as the founder of democratization in Myanmar, a process which it claims it would “consolidate” if it was to win more seats. While such a portrayal might be simplistic, it is not outright wrong considering the role of the military in Myanmar’s bumpy road to democracy and the close connection between the military and the party. If the narrative sticks with voters, it is set to have far-reaching consequences for the NLD which makes its own claims about introducing the democratization process.

Interestingly, the USDP changed its election strategy for ethnic minority constituencies. The party did not contest in Lai-Hka, Shan State (Pyithu Hluttaw); Matupi, Chin State (State Parliament); and Rathedaung, Rakhine State (State Parliament). U Than Htay, the party’s chairman, commented on the move by saying that the USDP wants the victory of ethnic parties because they are most able to represent the voices of ethnic people in these areas. Considering the party’s track-record on relations with ethnic minorities and their representatives, the statement should not be taken at face value. However, it may indicate that the party has learned from past mistakes.

The party’s decision is better understood by looking back at the 2017 by-election in which 12 out of 19 vacant constituencies were in ethnic minority areas. Back then, the USDP decided to run in all the constituencies but won in only two ethnic constituencies (Chaungzon, Mon State, Pyithu Hluttaw; and Keng Tung, Shan State, State Parliament). The NLD won 9 seats in the 2017 by-election, but only 2 of those seats were in ethnic minority areas, one of them being the constituency of the vice president Henry Van Thio. In fact, the NLD even lost in two constituencies in which they had won in 2015. One of them, Chaungzon, became a symbol of the NLD’s inability to consider the voices of ethnic voters when the party decided to name a newly built bridge “General Aung San Bridge” rather than honoring local histories.

The diverging strategies for campaigning and contesting in ethnic minority constituencies of the two main parties are going to be defining characteristics of the 2020 elections, should they remain unaltered. Currently, the USDP appears more clear-headed and it’s not unlikely that the party’s empty gestures of sympathy might sway at least some voters. The NLD’s strategy seems misplaced in light of the party’s failure to increase support in ethnic minority areas and makes the party appear locked into a self-image of a party of all people that no longer seems realistic.

While the parties differ in their electoral strategy in ethnic minority areas, they have moved closer together too. The increasing importance of the unity campaign narrative in the NLD and the party’s strong man attitude to resolving disputes with other parties are leading to a semblance between the parties. This is enhanced further by the USDP’s move to strengthen its image as a democratisation force, an argument that has become more potent because the successes of the party between 2010 and 2015 are increasingly viewed in comparison to the NLD’s current term in office, that has not brought the same kind of development leaps. The argument might seem prone to criticism because it addresses images rather than political substance but, in a country, where voters make their decisions based on party identities rather than party platforms it stands to have an impact.

The NLD’s spokesperson Dr. Myo Nyunt said that the party already has a policy that among those who were competing for candidacy with equal qualifications, priority is given to women, ethnic people and youth. However, out of 13 candidates from the NLD who contested in the 2018 by-election, there was only one female candidate. He commented on this decision that they had no chance to look at gender equality since the party only focused on victory.

The NLD is not alone with this problem. The USDP failed to select a single female candidate in all 10 constituencies it contested in. U Thein Htun Oo, the party’s spokesperson said, “we do not have a quota policy for the women and youths. We only prioritize those who can execute their duty.” Out of 69 by-election contestants, only 7 were women and none was able to win a seat. Yet, in a country with 51.8% women, 32% ethnic minorities, and 42% aged between 25 and 54 years, any rhetoric to take affirmative action against the “Burmese old man politics” has not even found its way into the general discourse.

In the 2015 general elections, 5.3 candidates competed in each constituency on average. This number remained roughly the same in the 2017 by-elections (5.0 candidates) and remained the same in the 2018 by-elections (5.3 candidates). If we were to consider these numbers alone, we could conclude that the competitiveness has remained the same. While this might be misleading, considering the myriad factors that shape competitiveness, the stability of the number is interesting because it tells us that ethnic minority parties, smaller issue-based parties and independent candidates have not stopped fielding candidates despite an electoral system that puts them at a distinct disadvantage. In fact, even more parties entered the field. The 2018 by-election was the inaugural election for 5 new parties, which were all established after the 2017 by-election: Myanmar People Democratic Party, Rakhine League for Democracy, People’s Workers Party, Union Nationalities Federal Democratic Party, National United Democratic Party (NUD).

Yet, not only is the extent of dominance of the NLD and the USDP in the ethnic areas a serious challenge for ethnic parties, but the vote split among them remains a main barrier too, with many failing to even win seats in the respective regional parliaments. The ethnic parties only got 11% of the contested seats in the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw in 2015. As the system elects only the candidate who gets the greatest number of votes, whether that number represents a majority of all the votes or not, the ethnic minority parties were heavily affected by the split of votes. In an interview, Dr. Myo Nyunt, the NLD spokesperson, refused to answer the question of whether the party had any plan to make an alliance with ethnic parties. A proposal to adopt Proportional Representation (PR), which is believed by many to be a better system, was rejected by then-Speaker of the Pyithu Hluttaw Thura U Shwe Mann, quoting the establishment of the Constitutional Tribunal, and saying that such a move would be unconstitutional.

To counteract vote splitting, ethnic parties have gone through with a series of party mergers. A good example is the recent merger of Chin parties. In the 2015 election, no Chin party won seats in the regional or national Hluttaws. The failure prompted talks between the Chin Progress Party (CPP) and the Chin National Development Party (CNDP) in 2016, which were later joined by the Chin League for Democracy (CLD). An agreement was finally reached on the 16th of October 2018, merging all parties under the name Chin National League for Democracy (CNLD). Yet, the merger came after the deadline for the submission of candidates for the 2018 by-election.

Several other ethnic parties have undergone similar processes. In Kachin State the Kachin Democratic Party (KDP), Kachin State Democracy Party (KSDP), the Kachin National Congress (KNC), and the Union and Democracy Party of Kachin State (UDPKS) formed the Kachin State Party (KSP).

In Karen State, the Palon Sawor Democratic Party (PSDP), the Karen Democratic Party (KDP), the Karen State Democracy and Development Party (KSDDP) and Karen National Democratic Party (KNDP) merged to form the new KNDP (the name of the one founding member party). Mann Aung Pyi Soe, the vice chairman of the Palon Sawor Democratic Party found vague but telling words, saying “I don’t want to mention what the NLD is doing for our rights because the Karen already understand it.” The NLD-led Karen government has received a lot of criticism since its controversial decision over the Asian Highway project. In a town hall meeting with the local farmers whose fields were flooded because of the upgraded roads, Nan Khin Htwe Myint from the NLD, the Chief Minister of Karen State, rebuked a young farmer who had raised concerns of the community by saying, “this [his voice] is by no means the people’s voice. This [his voice] is the voice of destruction.”

In Mon State, the All Mon Region Democratic Party (AMRDP) and the Mon National Party (MNP) formed the Mon Party. In Kayah State, the Kayah Unity Democracy party and All Nationals’ Democracy Party merged to form the Kayah State Democracy Party.

Yet, these newly-formed parties will have to prove that they can really pool their resources, connect with voters and bring home victories in the electoral arena. Unsurprisingly, more popular ethnic parties have by-and-large refrained from joining the mergers. The Shan National League for Democracy (SNLD), which won 3 seats in the Amyotha Hluttaw, 12 seats in the Pyithu Hluttaw, and 25 seats in the State Parliament in 2015, has no plans to form stronger alliances. Potential ethnic partners in Shan State, such as the Shan National Democratic Party (SNDP), stand too far apart politically.

It will also be interesting to see whether the recent party mergers will stand the test of time. One of the earliest party mergers, combining the Arakan League for Democracy (ALD) and the Rakhine National Development Party (RNDP) to form the Arakan National Party (ANP) in 2014, was initially very successful (10 seats in the Amyotha Hluttaw, 12 in Pyithua Hluttaw and 22 in the State Hluttaw), but split again in 2017 due to conflicts between party members.

In any case, the expectations of the party mergers are high as smaller ethnic parties are becoming more and more desperate for possibilities to get seats in the various parliaments in the face of NLD and USDP influence in ethnic areas. The frustrations go back to before the 2015 election, when the United Nationalities Alliances, made up of 8 parties, proposed the idea of an alliance to the NLD. The NLD, however, failed to respond before the deadline for the submission of candidates. As a result, the ethnic parties felt neglected. The SNLD, which had a leading role in the UNA, issued a statement declaring that the party would not form any alliance in the future in response to the NLD’s blunder.

Other ethnic parties also felt neglected by not being consulted, or by inconclusive meetings about important appointments related to ethnic affairs, such as the ethnic affairs ministers or chief ministers in the ethnic regions. “Even the Ne Win government didn’t appoint a man from outside our state as the Shan State Governor,” said Sai Nyunt Lwin, the SNLD’s General Secretary. The SNLD also complained about the appointment of a Burmese dentist as the Chief Minister of Shan State without consulting them. Sai Nyunt Lwin rejected an offer for a minister position in the state cabinet. However, he refused to state his reason. The party also rejected an offer by the NLD government for the position of Union Level Deputy Ethnic Minister with the reason that that position had nothing to do with federal union building and constitutional amendment, the issues at the core of the party’s mission. Nai Layie Tama, the General Secretary of the Mon National Party, said that there had been no discussion with the party over the NLD’s decision to appoint Naing Thet Lwin, the party’s vice chairman, as the Union Minister for Ethnic Affairs and that it made them feel uncomfortable. On the other hand, the ethnic leaders were afraid that they could move even further away from the NLD. “We are worried that if we disclose the reason for the refusal, we might be apart from the NLD,” said Sai Nyunt Lwin when asked for reason for the refusal of the offer by the NLD to make him a minister in Shan State Cabinet. Nai Layie Tama said, “we issued a statement to show that we continue to support the NLD and because we do not want the Mon People to worry that there is a rift between the ruling party and the MNP.”

It will remain to be seen whether ethnic party mergers can be a vehicle for navigating the difficulties the parties are facing and serve to improve the parties’ relationships with the NLD. If they do, they stand a chance to alter Myanmar’s political landscape in general and potentially shape the way major parties think about pacting and cooperation.

The effect of the 2018 by-election is not limited to the selection of representatives in a few constituencies but illuminated key trends that stand to shape Myanmar’s political landscape in the time leading up to the 2020 general election. The NLD and the USDP have been altering their campaign narratives and now appear to have moved closer together. Increased indistinguishability could have negative effects, especially for the NLD whose image has long been built on being an opposition force. The USDP has adopted a new approach to contesting in ethnic constituencies, carefully assessing its chances for victory before making the decision to contest. It has coupled this decision with a narrative that seemingly holds ethnic policy makers in high esteem. The tactic is undermined by the USDP’s policies towards ethnic minorities but is likely going to fare better than the NLD’s approach, that remained unaltered. The NLD would be well served by reconsidering whether it is in its interest to try and enforce an image of a people’s party that is the only “right” choice, rather than making constructive alliances with ethnic parties who are still not entirely alienated.

Ethnic parties no longer rely on potential pacts with the major parties but have increasingly merged to increase their influence. If they are successful in maintaining mergers, pooling resources and convincing voters this change has the potential to be the most far reaching yet.

Following the trajectories of these developments will be key for understanding the changes in Myanmar’s political landscape in the next two years.

Han Htoo Khant Paing studied Business Administration at Yangon University of Economics. He devoted most of his student life to challenging Students’ Union leadership roles including Vice-President at YUEco SU. He initiated university development projects for the enrichment of students’ campus experience. He was also the Editor 1 of The Uptown of Wealth Campus Magazine and an active contributor of various articles and essays. Currently, he is a Political Science student at Yangon School of Political Science, having joined the organisation in 2013. He researches the separation of power in different government systems and the impact of electoral systems on political parties.

Richard Roewer is a DPhil student at the University of Oxford, where he is a member of St. Antony’s College, and a doctoral student at the Institute of Asian Studies at the German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA). He conducts research on the consequences of democratic party formation under authoritarian rule with a focus on the NLD in Myanmar. Richard is also the founder and chairman of the Initiative Austausch e.V. (Exchange Initiative), a registered independent non-profit organisation that supports political education and participation. In this capacity, Richard organises the Political Education Programme for Junior Politicians (PEJP).

Like This Article