Wayland Blue explores the potential of community-based financial services for poverty alleviation.

Myanmar is the largest source of migrant labor in the Mekong region due to underdevelopment, internal conflict, and a perception that better jobs and greater security are available in neighboring countries—especially in Thailand. In the town of Mae Sot, a major land border crossing between Thailand and Myanmar, the majority of migrant workers receive relatively low wages working in agriculture, construction, manufacturing—especially of textiles, as well as the service sector, such as housekeepers and restaurant workers. While the low wages are offset by the low cost of living in migrant communities, which are often semi-permanent settlements or subsidized by employers, low incomes leave many at near-subsistence levels and vulnerable to economic shocks. These often take the form of medical emergencies and loss of employment. The economic situation, especially amid the COVID-19 pandemic is similar to that faced in rural communities within Myanmar, with the key difference being the absence of active conflict.

Compounding this vulnerability, many migrant workers face difficulty gaining access to open market financial services including the banking system due to language barriers and lack of appropriate legal documentation. As a result, the most marginalized often turn to black-market money- lending at exorbitant interest rates. For example, trusted local informants working in community-based organizations report monthly interest rates on principle for such loans as high as 20 percent. This systemic financial insecurity can result in individuals becoming trapped in expanding debt that is effectively unpayable at their level of income leaving them at greater risk for violence and further exploitation.

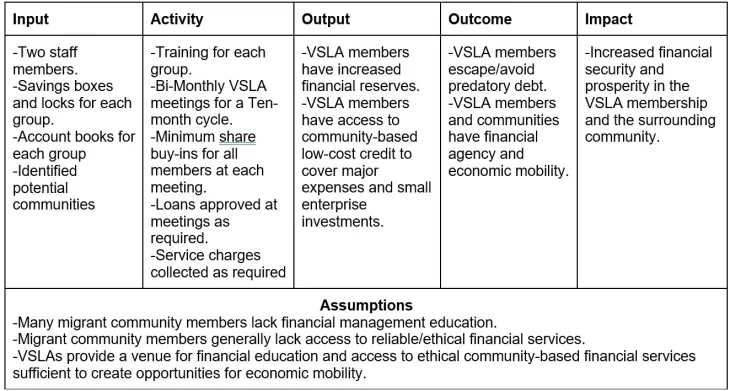

A primary objective of the Shade Tree Foundation, a Thailand-based NGO focused on child and family protection in the Myanmar migrant population, is improving the financial security of migrant families, specifically in Mae Sot, Thailand. This article outlines the concept and initial impacts of Shade Tree Foundation’s Village Savings and Loans Association (VSLA) program, which aims to increase financial literacy and provide access to reliable financial services in migrant communities. The program also shows the potential for further implementation within similar communities in Myanmar.

Originating in West Africa, the VSLA is a form of community-based microfinance that has shown significant benefits across numerous cases. VSLA programs have contributed to improved human security and greater levels of entrepreneurship in several development contexts. The VSLA concept differs from traditional microfinance in that there is no external seed money provided. Rather, VSLA groups are normally composed of members from a single community who build their VSLA fund from their savings throughout a mutually agreed upon time period comprising the VSLA group cycle.

Members save into the fund by buying a variable number of shares based on how much they wish to save and the established rules of the group, which may limit the number of shares a single individual can hold. The group then provides credit by making loans to individual members for group-approved expenditures and investments—like school fees, and capital investments to start small businesses. These loans are paid for with fixed low-rate service charges which are paid into the communal pool.

At the end of the cycle, the accumulated service charges on loans are equally divided by the total number of shares and the resulting quotient is added to each individual share. Members then receive their total savings with profit for their personal use. As a low-cost, community-based program, VSLAs have considerable advantages in flexibility and ease of implementation to provide accessible financial services to marginalized communities and promote greater economic security.

It is important to note that VSLA programs and microfinance, in general, are not without controversy, both globally, and in the Myanmar context. A key objective of microfinance is the provision of credit for entrepreneurship and human capital development for those too marginalized to access conventional banking. However, this objective is challenged under stagnant or deteriorating economic conditions in which borrowers are forced to use credit to pay for basic consumption or emergency expenses rather than reinvesting in capital purchases or skills development. The problem can compound when the same borrowers, unable to invest and turn a profit, are also unable to service their loans without taking on additional debt from the same or other creditors. These are precisely the problems some have identified in the Myanmar context where systemic underdevelopment and poor regulation of the microfinance industry have raised critical doubts as to its effectiveness and justify concerns of predatory lending.

The crucial difference between traditional microfinance and the VSLA concept is that, under ideal conditions, it is implemented to fit specific contexts and is regulated at the community level. However, there remains a risk of exploitation in settings with low social trust and existing marginalization. Furthermore, access to VSLA programs does not remove the problems of broader economic instability forcing borrowers to divert credit to basic consumption—thus continuing the vicious cycle of taking further loans to service existing debts. Nevertheless, well-regulated VSLA programs with high levels of community participation and trust have shown promising results for increasing financial stability, food security, and women’s empowerment in Rakhine State, perhaps the most systemically underdeveloped and unstable region in Myanmar. Thus, the potential and performance of VSLA programs elsewhere merit further exploration.

Since 2017, Shade Tree Foundation conducted training and coached VSLA groups in several communities throughout the Mae Sot area to increase financial literacy and encourage entrepreneurship in the migrant population—particularly among women. Group locations are referred by trusted informants and word of mouth. Community members who volunteer to join the VSLA group receive initial training and elect officers. All transactions in the form of savings deposits, loans, and service charge collections are conducted during scheduled meetings throughout a 10-month period which comprises a single VSLA cycle.

An average Shade Tree Foundation VSLA group is about 12 members from the same community, mostly women, and normally employed in factory or agricultural labor. They typically meet every two weeks in a community common area to open the deposit boxes, buy shares, request and vote on loans to fellow members, and update the group account books. Members requesting loans present their case, which is openly discussed and requires majority consensus to be approved. Shade Tree Foundation staff members observe and coach but gradually step back as the members become more confident in managing their group’s affairs.

Shade Tree Foundation’s initial inputs include qualified staff to train and coach the individual groups, transportation costs to and from VSLA group meetings, as well as deposit boxes with locks for each group to secure the group fund between meetings. Shade Tree Foundation staff serve only to provide training and coaching for the groups and do not have decision making authority, neither are they permitted to save into the group fund.

An important preliminary question regarding the outcomes for Shade Tree Foundation’s VSLA program is: how well did it serve to provide reliable financial services for its members?

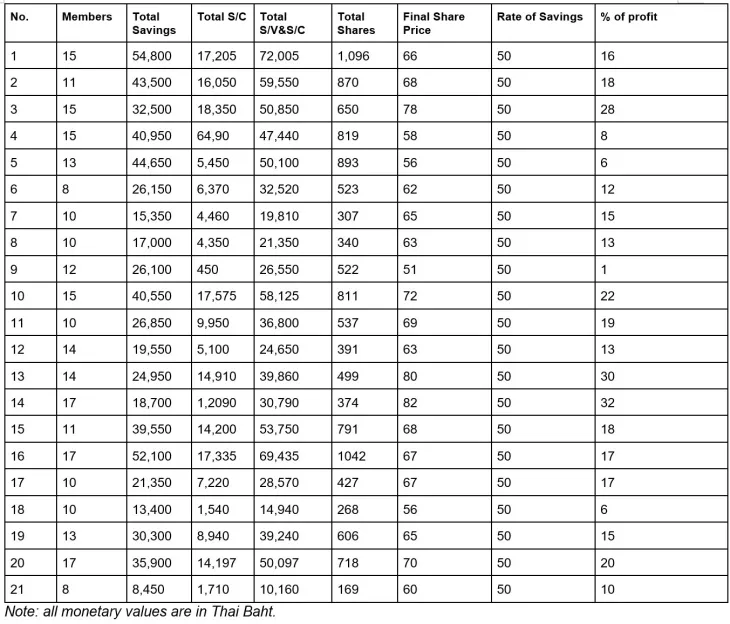

I provide an answer by analyzing first cycle share-out results for all groups with complete data from 2017 to the present. I proceed by calculating the amount of savings and profits from loan activity members who were able to accumulate. I then compare this with available data for prevailing wages to assess the benefits to members in increasing their financial security.

The group membership and savings behavior we observed in the first cycles is highly variable and is likely impacted by the different social and economic contexts of the individual communities. The majority of Shade Tree Foundation’s VSLA members are originally from Kayin State and Bago Region and live and work mainly in agricultural settlements or factory communities. Higher rates of savings in some groups likely indicate members have more reliable employment and can afford to save more, which supports the understanding that broader economic conditions remain important factors that microfinance alone cannot address. However, we can draw some general preliminary conclusions about the program’s effectiveness in providing reliable financial service.

The first key metric is the average individual savings. For the first cycle, this was 2,377 Baht (SD = 879). The second key metric is the final share-out portion which is the sum of individual savings and rate of interest the groups were able to generate. This is calculated in the three following steps.

At share-out, members receive the total of the shares they have purchased at the final share price. The average profit was 16 percent (SD = 7.8 percent), and the average share-out portion was 3,121 Baht (SD = 1,171).

Additionally, each group’s profit is linked to the loans made to group members with a higher profit rate reflecting more transactions. The profit rate for this program is also moderately correlated to group size (0.44). Therefore, higher profits infer greater economic activity with the major benefit that profits on credit remain in the community and are likely to increase with group size. Thus, in terms of providing a safe and ethical venue for savings, loans, and investment we can assess the VSLA program effectively meets one intended outcome of providing reliable financial services to migrant communities.

A critical consideration that remains though is that the current safety and effectiveness of the program as observed here is dependent on community trust and transparency. Without strong intergroup accountability facilitated by democratic management and detailed records keeping, the system is vulnerable to fraud and exploitation. Furthermore, Shade Tree Foundation staff have observed many group members still carrying significant debt loads from other creditors. Nevertheless, we can assess some overall financial benefits to the Shade Tree Foundation VSLA members.

A relative comparison of the impact for VSLA members in terms of overall financial security with the larger migrant population is confounded by limited data and the instability of the population. In particular, we lack a reliable rate of consumption and savings for the migrant population to which we can compare the groups’ performance. However, we can use the standard minimum wage as a proxy for migrant workers’ income to assess the significance of the financial reserves generated by the members.

The official minimum wage for Mae Sot and Tak province, Thailand as of 2018 is 310 Baht per day, which translates to 6,820 Thai Baht per month assuming a five day work week and uninterrupted employment. In comparison, the mean share-out portion was equivalent to 46 percent of monthly income at minimum wage. An important caveat is that many migrant workers receive below minimum wage and are not fully employed. This is especially the case for women who also comprise the majority of Shade Tree Foundation’s VSLA members. Thus, when combined with low-interest credit available during the cycle, we can reliably conclude the VSLA program positively contributes to increased financial security for its members.

Shade Tree Foundation’s VSLA program director further elaborates on perceptible cognitive shifts in members’ outlook towards entrepreneurship and finances in general saying:

This VSLA saving discipline leads the families in how to manage the income and control the expenses. As a result, the attitude and behavior have been changed by the financial training. Most of the saving members see clearly that they no longer want to be the workers and have prepared for doing business in the future when they return to Myanmar.

Ma Ching San, Shade Tree Foundation VSLA Program Director Tweet

The VSLA program has been effective as a low-cost venue for reliable financial services in Myanmar migrant worker communities, as well as increasing the financial security of its members. Although the environmental context of Mae Sot differs from much of Myanmar in terms of security and development, the success of the VSLA concept here shows significant potential for wider implementation by community-based organizations and NGOs within Myanmar.

Especially considering Myanmar’s large rural population and differential levels of development and access to financial infrastructure, VSLAs present a vital low-risk tool for poverty alleviation and economic empowerment for the most vulnerable members of society.

Additionally, the qualitative effects of VSLA membership on increasing members’ financial literacy and personal agency are perceptible, but not well understood. Further research is required to better understand the cognitive dimension of VSLA membership and how it affects financial acumen and entrepreneurial behavior. A better understanding of the mental and emotional processes of gaining increased personal agency will have a significant benefit to promoting the economic mobility of the most vulnerable, not only through VSLA type programs but also through a wide range of development efforts.

Wayland Blue currently volunteers as the director of research and evaluation for Shade Tree Foundation. He holds a BA in Political Science from UC Berkeley and an MA in International Relations from American Public University System.

Shade Tree Foundation: Instagram (@shadetreethailand), Twitter (@ShadeTreeFound2)

For English-language content, check out The Charis Project: Instagram (@thecharisproject), Twitter (@CharisProject)