Edgard Rodriguez considers the role of investing in think tanks to support Myanmar’s ongoing reforms.

The Republic of the Union of Myanmar has made significant strides in modernization and in achieving greater openness since its days of being isolated from the Western world. Nevertheless, the country still ranks high, above Pakistan and North Korea, in the 2019 Fragility State Index.

As the transition continues, it has become clear that one of the biggest challenges for the civil government is to balance the interests of many groups, representing the country’s 53 million people and more than one hundred different ethnic groups. Myanmar’s ministers and MPs face in-trays filled to the brim with demands: they need to propose new laws, provide better public services, attempt to end the world’s longest conflict, and craft policies that can achieve sustainable, positive outcomes. A recent paper from The Asia Foundation, Managing Change: Executive Policymaking in Myanmar, recommends that high quality, comprehensive data and analysis can help ease the demands on policymakers to address the country’s economic and social problems.

But where might these data and analysis be found? Think tanks can provide this much-needed advice, and become an effective resource for governments. According to the 2018 Global Go To Think Tank Index, Asia is now home to about a fifth of the world’s think tanks. Myanmar’s think tanks are now emerging as an active addition. Donor support to this segment of civil society can make a solid contribution to ensuring the provision of evidence-based advice for policymaking. Investments in local think tanks could help produce contextually appropriate, effective policy options in the complex context of Myanmar.

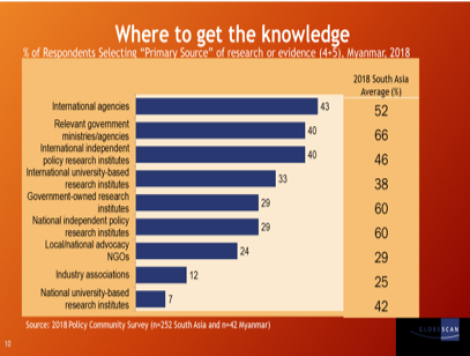

Findings from the groundbreaking 2018 Policy Community Survey of Myanmar show that think tanks in Myanmar must improve to ensure that officials have easy access to accurate information for national policy formulation. Only 29 per cent of the country’s policymakers sought information and analysis from government or independent in-country research institutes. The same survey conducted in five South Asian countries found that 60 per cent of South Asian respondents turned to their think tanks for their information needs. The results for universities are even more surprising: 42 per cent of South Asian respondents sought out national university institutes, while only seven per cent of Myanmar respondents did. This finding suggests very poor confidence in the research produced by the country’s universities following decades of systematic neglect.

For local think tanks to become the preferred source of data and evidence and thus play a greater role in Myanmar’s development, the survey recommends they focus on improving research quality, increasing the availability of experienced and trained staff, and building greater awareness of their services. While not representative of the views of the entire policy community in the country, the survey does gather valuable perceptions from senior-level participants to understand the strengths and weaknesses of local think tanks.

Despite this low confidence in think tanks generally, a handful of institutions that have good connections with, and access to, government are facing an overload of demand. Two well-known think tanks responding to the current administration’s needs are the Renaissance Institute in Yangon and the Myanmar Development Institute in the nation’s capital, Nay Pyi Taw. Because Myanmar government policy development and implementation capacities are still evolving, there is a strong appetite for the work of these two institutions.

The use of an evidence-informed approach to policymaking in Myanmar remains relatively new and many institutions are still settling in. Policymakers’ attitudes towards external advice differ depending on the policymaker and level of government: an experienced director-general in an influential ministry in Nay Pyi Taw is likely to have a very different perspective from a member of parliament in one of the states or regions with less experience in policymaking, who may simply not understand research and evidence.

The potential exists for smaller think tanks to provide advice. There is an opportunity to create demand from policymakers, if think tanks provide innovative ways to offer useful and accessible information. Think tanks in Myanmar have mushroomed, despite the constraint of operating in a restricted political space. There is a need to widen this space to make better use of research and evidence to support public debate with new ideas from independent think tanks. Media articles in Myanmar Times and Frontier have make the case for a role for civil society under the civil administration. This is all the more pressing as the next elections planned for late 2020 approach and public debate intensifies.

The key question for donors as a new electoral cycle looms is how much support is needed for more think tanks to develop capacity for policy-relevant research?

As Myanmar’s transition continues to unfold, newly established think tanks struggle to receive the support they need to become effective and sustainable. Myanmar’s think tank landscape will change rapidly, with some organizations flourishing, while others fail to reach long-term stability. This should be perceived as a healthy situation, but one that presents risks to donors who are looking to provide significant support to young and less established institutions. IDRC and Kivu International undertook a needs assessment to prepare for this task, finding many needs that are common to all think tanks:

Other needs identified in the Kivu International and IDRC needs assessment include:

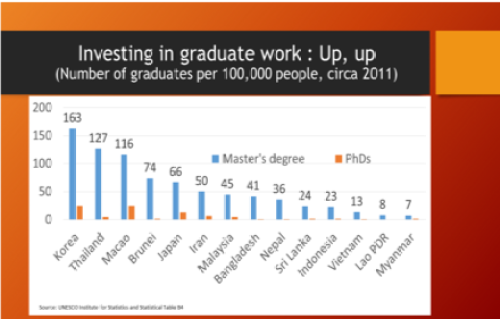

A sound higher education system could help address these needs and Myanmar is starting to tackle reform in this sector. It will take decades to create a vibrant and resilient community of local, independent researchers and policy advisors. In the meantime, think tanks provide an effective way, if not the only solution, to rebuild a society that is better positioned to provide thoughtful and prompt input into the many development challenges that the country faces. Donors should take note that investing in nascent think tanks could be one of the best investments they can make to nurture the world’s transitioning political systems, Myanmar being a compelling case in point.

To learn more about these projects visit:

Building Emerging Think Tank Capacity in Myanmar

Building organizational development among Myanmar think tanks

Edgard Rodriguez is a senior program specialist who leads the International Development Research Centre – Global Affairs Canada funded Knowledge for Democracy Myanmar Initiative, aiming to build the capacity of leaders to carry out research and evidence-based public policy.