Khine, Nway Oo, and Peter (pseudonyms) express what they stand to lose in Myanmar’s Spring Revolution and why they continue the fight.

On the 1st February 2021, my aunt woke me at 6am. She told me, “Min Aung Hlaing is conducting another military coup.” I woke up immediately, confused. “Is this a nightmare or is it really happening?”, I thought to myself, shocked by the news.

I have been facing down Myanmar’s military junta since I was in my mother’s womb in 1988. Born in 1989, I am now 32 years old, the same age as my parents during the 1988 uprising. But our battle for democracy and human rights goes on.

My first response to the emergency was to go out and buy essentials: rice, oil, a torch, a radio, candles, and batteries. From past experience, we knew exactly what we would face under military rule. When I finished, I felt blank. I struggled hard to focus on staying calm and coming to terms with the situation. I knew that if I could achieve this fundamental step, I would be equipped to focus on what to do next.

The voice of the people is a fundamental element within a democratic political system. As an independent researcher in spatial design and participatory place-making, I believe in listening to people’s voices. I understand that compassionate listening is a priority in every project; it is the best way to find comprehensive solutions for a better living environment. Inspired by this approach, I decided to express my voice as an individual citizen through writing. On the 3rd day of the coup, I decided to write, to make my voice heard as a citizen.

On the 28th day of the coup, I finished this draft and handed it over to my co-authors overseas. I felt relieved and satisfied with what I had accomplished. I saw it as the first strike in a long battle.

However, later the same day, my optimism disintegrated. News reached me that my father had been detained due to his involvement in the uprising. I felt as though the sky had fallen on me. He has now been detained in prison for more than a month without charge, in violation of his human rights. At his first trial, on 8 April, they did nothing but postpone the trial for another date.

My involvement in the uprising against the military coup began when I was just a fetus in 1988. Now, at 32, I am the same age as my parents during the 1988 uprising. Now, father and daughter fight side by side.

According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), as of 23rd April 2021, there are already 745 people killed (more than 40 are underage), 3371 people detained (like my father, thousands are still awaiting trial, and are being abused in the meantime) and more than 1118 arrest warrants (under 505-a) for speaking out against the coup. The figures are still increasing, and there are ongoing deadly attacks and arrests against unarmed civilians. Those events are obvious proof of how our battle for democracy and human rights remains unfinished. Like us, many other fathers and daughters, mothers and sons are now working to resist the military’s deadly crimes against humanity.

As Ermonela Jaho, the Albanian-born soprano, said in her interview for Global Woman Diva Program, “live every day to the fullest and you have already made the future a reality.” We are struggling for our right to live every day to the fullest. Under a dictatorship, there is no room for people to create their own destiny. I owe it to myself to design my life and live fully. For that reason, I cannot accept living in a dictatorship.

This time, I believe we will win because we must.

Perpetrating an unjust military coup in the middle of global pandemic clearly demonstrates that the power-starved military in Myanmar has no empathy for civilians. We have been suffering a combined health, economic and social crisis resulting from Covid-19 for over a year. We are awaiting the arrival of the vaccines and preparing for Myanmar’s recovery. Even so, with whatever strength we have left, the people are non-violently resisting the coup-makers in spite of our fear of Covid-19 and the deadly attacks against us.

Myanmar society has suffered the trauma of living of under an oppressive regime for more than 50 years. We are all tired of being attacked by those who act against morality and humanity. The putschists will never stop on their own! Now, it is the civilians’ duty to stop them.

Though we know we will win this battle, Myanmar still risks facing further political, economic, and social crises. With each subsequent crisis, recovery becomes harder than ever.

The following are the major political and socio-cultural issues impacted by this selfish and egotistical act on the part of the military in Myanmar.

This coup poses a major threat to the reform of the 2008 Constitution.

To accelerate the peace process and ensure federal democracy in Myanmar, the 2008 Constitution has to change. This constitution was drafted by the dictators and designed to safeguard the interests of the former authoritarian regime.

To allow room for justice, fairness, inclusion and respect, the values of diverse civilians from all ethnic groups should be reflected in the constitution of Myanmar. But, in reality, the views of civilians were ignored and the 2008 Constitution does not represent the will of the civilians.

Under the dictatorship governance, the citizens’ voices will be silenced even further.

Recently, on 31 March, the Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH) declared the abolition of the 2008 Constitution. This is the first step towards federal democratic state-building. Despite the challenges facing us, this is a ray of hope among the ruins.

Our experience clearly reminds us that there is no room for democracy in a land governed by a dictatorial regime.

We grew up without being educated about how to claim our rights. We were not taught tactics to identify what we really want as a society, what we want to change and how to make changes as a collective.

Military rule has failed to provide us with tools for (a) developing self-awareness, the ability to question and search for one’s true self; (b) knowing and valuing one’s own existence, and knowing how to respect others; (c) building self-confidence; (d) developing critical thinking skills that account for different perspectives; (e) building understanding and trust; (f) knowing how to conduct constructive arguments and knowing how to share, communicate, collaborate and commit to engaging with one another, in order to transform our thoughts into actions.

Without these key tools for self-searching, expression, communication and collaboration, we could not fully develop our self-awareness, self-esteem, and self-management. We became weak and were easily manipulated and brainwashed. The dictators conditioned us to have a “fear of expression” rather than “freedom of expression”.

We learned that the right way to live in Myanmar is to follow and obey our parents, our teachers, our elders, our religious leaders, and our government. Asking questions, arguing, or refusing to do as we are told is considered rude, even evil. The elders used to say, “We are older than you, we have lived longer than you and so we know you better than you know yourself. It is better that we manage your life than you manage your own.”

The prevalence of this type of thinking shows how the junta has shaped our psychology, since our elder’s time. Military rule has transformed our independence so much that conservative behaviors became the norm. What started with the junta using fear to oppress, nowadays operates as a kind of conservatism that claims to protect ‘culture.’ In reality, this ‘culture’ controls even our slightest social freedoms.

During the last five years, our dreams started to come true: we acquired much greater freedom of expression and the opportunity to put our thoughts and desires into action. However, rather than reconstructing the country, our time was wasted fixing problems caused by failures of understanding, communication and collaboration. Without the key tools mentioned above, we failed to see things from different perspectives, and we tended to express prejudices in a very subjective way.

Ego also plays too much of a role in the way that our people act and overwhelms our ability to communicate and collaborate. We believe that this egocentrism, a lack of openness to understanding, and an unwillingness to build trust are the root of the conflicts happening in Myanmar. Expressions from egocentric points of views provoke unconstructive hate speech and inhibit the potential to develop just and balanced solutions, such as can be seen in the Rohingya crisis and any other conflicts amongst the different ethnic groups in Myanmar. Our ingrained “fear of expression” caused us to underestimate the value of diversity.

We understand that five years is not enough to build a seamless democratic country, but ceasing conflict and instead making efforts to collaborate would greatly increase the speed at which we can see a difference. To acquire true democracy in Myanmar, we cannot rely solely on Daw Aung San Suu Kyi; we should look to ourselves too. If we do not have the societal and interpersonal habits required for a constructive dialogue, we will never see the beneficial outcomes brought about by democracy. Participatory democratic practices must be performed with urgency in reconstructing a Myanmar adapted to our personal and societal needs of today’s world. To make this a reality, Myanmar needs to cultivate democratic knowledge and practices.

Our battle for freedom and democracy is not yet won. We are only just beginning to realise the problems we have to tackle. But, again, today, the democratic transformation of Myanmar is being undermined by the unthoughtful, unjust, and disloyal act of the military coup.

Jane Jacobs writes that “cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”[1]

Indeed, it is only through people’s participation that we are able to develop better places for people, that respond to the problems and needs of each neighborhood. No outsider knows better than the local community.

Are government officers, mayors, and general administrators ready to set up the democratic governance necessary to manage cities, districts and townships with a participatory approach, working with the inhabitants and place-makers as stakeholders?

Myanmar is not yet in a position to give a satisfactory answer for this question. Even under the civilian democratic regime, Myanmar still needed to cultivate democratic knowledge and practices to ensure the participatory governance. However, the Myanmar Sustainable Development Goals include achieving the right to a safe and better living environment. Myanmar was figuring out the most comprehensive methods to bring more people into the process of creating people-led urban governance and development strategies.

The right to the city can be fulfilled only by means of democratic city governance that gives more space to people to participate. The dictators do not believe in participatory democratic governance. Thus, under the dictatorship, our dream for safe and better living environments for the well-being of the people will remain out of reach.

Sing loud. You shall hear other ears hearing. Look high. You shall see other eyes looking. Beat loud. You shall know that other blood is pulsing.

Rafael Alberti (Spanish Poet) [2] Tweet

We are making our voices heard through our uprising. We hold hands firmly and are working together to end the dictatorship and fulfill our own destiny.

We create a battle symphony with the sound of pots and pans!

We raise our three-fingered salute!

We march!

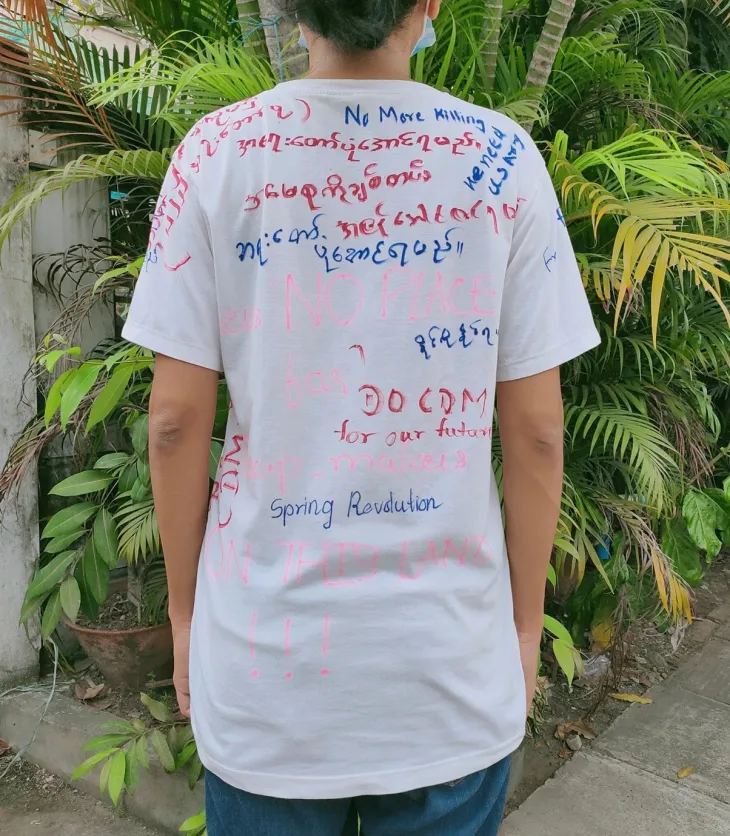

We stage creative uprisings through various forms of collaborative performance!

We help each other and show global solidarity!

We support the Civil Disobedience Movement!

Driven by our strong determination, we remain resilient against the deadly attacks.

There is a hidden gem in this battlefield that we can take advantage of to turn everything around. It will help us not only to defeat the military, but also achieve the federal democracy we dream of. It will determine the end result – who will pay and who will gain.

This key is the “synergy” born out of trust and cooperation between our diverse civilians

across the country, pro-democratic political parties and activists, the CRPH (The Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw), the EAOs (The Ethnic Armed Organizations) and pro-democratic supporters across the world. The coup-makers underestimate the power, resilience, and intelligence of the people.

In addition, the coup shows who our real friends, enemies and frenemies are. Because of this coup, we have begun to question the presence of China in Myanmar. Discussions about China’s purported support for the military makes us mistrust the country.

In order to achieve our collective dream for a functioning federal democracy, we first need to defeat the current military coup, then end ongoing attempts to reestablish a dictatorship. In the place of the existing military, we demand a trustworthy, faithful and responsible federal defense force in Myanmar.

Victory in this battle means a lot for civilians; not only the failure of the coup and the end of the dictatorship regime, but to end, once and for all, attempts to interrupt the process of building a federal democratic state.

We have only one another – our solidarity is our only weapon. We will never give up our rights to live freely and fully.

Khine (pseudonym) is a designer living in Yangon. She is passionate about exploring artistic ways of expressions and communications. Her focus is to take part in projects developing intercultural understanding and communication through design and artistic creations.

Nway Oo (pseudonym) is a researcher in Language Sciences based in Europe.

Peter (pseudonym) is an architect and film maker. He has led research, academic and curation activities in Alger, Addis Ababa, Istanbul, Yangon and Paris.