David Scott Mathieson discovers some curious displays in Pansodan’s thriving book stalls.

Along downtown Rangoon’s Pansodan Street, this city’s hub of humming bookstores and street stalls, there are rich discoveries to be had. From bestseller novels, political investigations, bodice-ripper love stories, biographies, textbooks, TOEFL tomes, poetry, photocopied versions of Western works on Burma, and, in the dustier corners of the Lower Pansodan venders, dog-eared Mickey Spillane pulp fiction, distressed Marxist-Leninist texts in Russian, almost nostalgic Myanmar Socialist-era propaganda magazines, and sinister – yet laughable – military State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC)-era xenophobic conspiracy theory agitprop. A few years ago I found a prize for my library: an original Ian Fleming picture book of his classic Chitty Chitty Bang-Bang to join the collection of James Bond novels.

For any bibliophile, the downtown second-hand scene is a treasure trove. It breathes a reading culture that Burma is rightly proud of. Yet what also fascinates me is the contradictions of so many displays of books, which languish alongside each other with apparent balance, even as the subject matter on many works on Rakhine State have deeply divided people inside Burma, and have fueled anger at the West for its perceived pressure to end persecution of the Rohingya minority. The renaissance of the Burmese publishing scene, including hundreds of new titles in Burmese and English translation, new venues such as Yangon Book Plaza, Weekend Book Street around the Secretariat, and fixed stores and the many street stalls, have multiplied the availability of contemporary or competing narratives.

If you believe you can tell a lot about a person by the books they read, or don’t, then checking out the top-sellers in Rangoon’s bookshops can occasionally be unsettling. Last September, I perused the bestseller list in one store on Upper Pansodan to find a new, and lavishly produced, Burmese language version of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf at number 3 (and costing 15,000 Kyat, a hefty sum). The towers of copies of the new volume were a disturbing sight in the midst of the Rakhine crisis ‘clearance operation’ by the Burmese security forces, which were then forcing hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims out of Northern Rakhine State into Bangladesh, amidst widespread reports of ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.

I was a little encouraged when I next, nervously, checked the same bookstore a few weeks later to find that a Burmese translation of Chinua Achebe’s masterpiece Things Fall Apart had shot to first place on the list, and that Hitler’s abominable tome had disappeared. As Daniel Kaldor’s new book on despot writings and ideologies, The Infernal Library reminds us, initial sales of Mein Kampf were dismal in 1925, the sequel the next year fared even worse –only becoming a bestseller after Hitler seized power in February 1933 when copies were snatched up by the hordes of ‘March Violets’ who surged to support the Nazi’s.

From a racist madman screed to a celebrated study of pre-colonial life in Nigeria was certainly an improvement, but I did muse on the meaning of people being drawn to a title of things falling apart in the midst of so much conflict all around Burma.

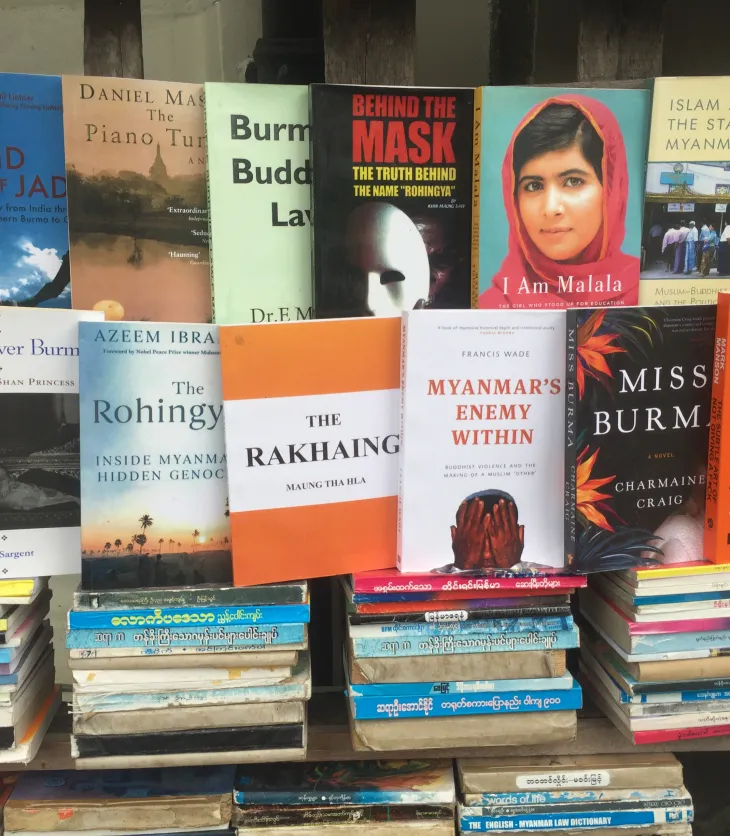

One confounding constant in the mix of booksellers of downtown Rangoon is the juxtaposition of books representing the competing narratives of the Rakhine crisis laid side by side for sale, with nary a complaint or protest from passing hoi polloi – let alone uber-sensitive ultra-nationalists. The word ‘Rohingya’ excites political passions in and outside the country, so it’s curious to see several books with that title publicly displayed alongside each other, as if inviting all to witness the polar opposite narratives that fuels the conflict and feeds the states of denial over mass atrocities that so many people of Burma are in.

I surveyed the motley selection at one well-stocked stand. Take for example a snapshot of this phenomenon in the above photograph. There were books with titles such as The Rohingya: Inside Myanmar’s Hidden Genocide by Azeem Ibrahim, a work riddled with errors and reeking of opportunism, yet which resonates with international peripatetic perceptions of the conflict despite its starkly obvious shortcomings. A shockingly racist, xenophobic, conspiracy theory screed entitled Behind the Mask: The Truth Behind the Name “Rohingya”, by Khin Maung Saw, with its dehumanizing artwork of an alien-type ghoul creature, proving one can indeed judge a book by its cover. The Spanish journalist Carlos Sardiña Galache, who has produced some of the most insightful, balanced, and principled reportage of the Rakhine conflict over the past several years, penned an excellent essay last year in the pages of the New Left Review of Behind the Mask and Azeem Ibrahim’s Rohingya book, which attempted to comprehend the perspectives of the crisis pulling in opposite directions. It is jarring to see both books displayed in downtown along the same bookshelves after reading Carlos’ carefully drawn critique as they represent the extremes of the debates over Rakhine State.

The bestselling Myanmar’s Enemy Within by Francis Wade, a potboiler of breathless reportage (based on a true story), that fuses a literary style with a tabloid analysis of the conflict— which some Westerners who rarely venture downtown are convinced could never be permitted to be sold openly given the furies of ethno-religious tensions in Burma, and yet is freely available for a spiffy photocopied version— will set you back 4,000 Kyat. The Rakhaing, a history of the Arakanese by Maung Tha Hla, that presents the central currents of Arakanese nationalism over the lost Mrauk U kingdom and the purported invasion of Muslims into Burma, and the threat Islam poses to Buddhism, is there too. Dr. E Maung’s Burmese Buddhist Law, outdated— but still an important read— is also present. Then Islam and the State in Myanmar, a fine collection of academic essays on religious conflict in Burma edited by the Australian scholar Melissa Crouch and released in 2016. Somewhat incongruously, copies of I Am Malala, by Malala Yousafzai, the Nobel Peace Prize winning Pakistani champion for the education of girls, who was pilloried on social media for her letter to Aung San Suu Kyi in late 2017 calling for protection of the Rohingya Muslims. All free to peruse or purchase.

Staples of many of these second-hand or photocopied illegal versions are present too; Bertil Lintner’s classic of conflict reportage Land of Jade, Thant Myint U’s sweeping history of Burma The River of Lost Footsteps, Charmaine Craig’s Miss Burma, Pascal Khoo Thwe’s From the Land of Green Ghosts, and Inge Sargent’s Twilight Over Burma, her account of being the wife and then widow of the Shan prince of Hsipaw, murdered in the military coup d’etat of 1962.

One recent addition, literally bookending many of the downtown displays, are English and Burmese versions of Mark Manson’s The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good Life, the Burmese language edition of which is currently Number 2 on the City Mart bestseller list. The pseudo-New Age manual of insouciance has apparently appealed to the book reading scene, and the laws of supply and demand are proceeding.

But what of all of these eclectic outlooks on the country and especially the Rakhine State conflict? All of them have grounds for furious political debate and serious emotions on the conflict, though not always with the facts marshalled. I asked one of my most approachable sa-ouk-hsaya (shop sellers, or, literally, “book-teachers”) why he sold them all? “They sell, like other books,” he said. Did he ever have problems with people passing by and objecting to the word Rohingya being so prominently displayed? “No,” he replied, “no-one really cares.” Do many people buy them? “Not really.” Why did he array them side by side? He shrugged, and looked at me as if I clearly didn’t understand the ways of book display. Then he told me, “People here care about eating and their own lives, they don’t care about all that.” How many people inside Burma actually care what foreigners write about the Rakhine conflict?

One would have thought such a tense environment over the widespread denial of the existence of the word Rohingya, let alone claims to that identity by millions of persecuted people, would incense violent ultra-nationalists to force a removal of such works from public sale. But then this is downtown Rangoon: cosmopolitan and with a sizeable Muslim population, and far more freewheeling in its intellectual appetites. It is doubtful if such insouciance would flourish in midtown Sittwe, the Rakhine State capital, now cleansed of most of its Muslim population in 2012 apart from the remaining ghetto of Aung Mingalar, or the central Burma city of Meiktila where anti-Muslim sentiment continues to simmer after the horrific violence of 2013 that killed scores of people.

There is no doubt the Rangoon book scene has come a long way from the crushing censorship of the Socialist and military dictatorship periods, when the cheap brown paper used to print everything from propaganda to poetry was sharply rationed. Many stores are now well-stocked with eclectic new Burmese authored works and waves of translations of English classics and contemporary popular books, with Mark Mason’s work being the current Zeitgeist. The cheaply produced photocopy versions of many classics on Burma abound, including many books that would likely have attracted the attention of the Special Branch not too long ago, include many books on Burma’s military.

But as Mandy Sadan has artfully analyzed in Tea Circle, many of the translations of English language works have serious limitations, her works included. Some are merely summaries; others have taken short-cuts around the facts in their interpretations, which have serious implications for how complex historical conflict events are perceived. Wendy Law-Yone wrote in the pages of the Times Literary Supplement in April this year about the publishing of the Burmese translation of her novel The Road to Wanting, which created an online storm of criticism. The wrong version, strewn with errors, had been printed, not the final version. What resulted was an online assault from readers against the well-known translator herself. Her defensiveness against the criticism was then condemned. Law-Yone is bemused by the reaction, questioning why there is more umbrage over perceived criticism of the national character than the substance of ideas, and links the incident with the nationalist response to criticism over abuses in Rakhine State: “What the vast majority of Burmese, at home and abroad, seemed to be protesting against was the affront of international censure” (italics in original).

On a recent research trip in central Rakhine State, I happened upon a local news journal in Burmese which I had inadvertently contributed to. An article from the Asia Times I had written in May about the Twitter account of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) had been essentially translated in paraphrase, but all the original details there, but with an editorial line imposed with I would never agree with. I am grateful to the plagiarist for not giving me credit.

But perhaps all this disregard for the display of contentious books harbors a deeper state of denial, that what appeals to the reading public is simply just not giving a f*ck about the horrors of what has, and still are, happening in Rakhine State and the rest of the country? That is the deeper concern. Does the book-reading public have open-minds about controversial works and their sale, yet a more enraged approach to perceived slights against identity and national pride in the anti-social media realm of Facebook? Or maybe many of the books on sensitive topics are avoided by most people, a legacy of the surveillance state which many analysts in Burma believe has staged a sinister resurgence? When the last several years have been marked by the relaxation of censorship on books, art and public debate (though with obvious limitations as the official assault on the domestic media has made clear) how much are these conditional freedoms in retreat?

One of the starkest examples of this recidivism was the recent sentencing of Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone of Reuters to seven-years imprisonment on trumped up charges of breaches of national security. Social media erupted in condemnation of the verdict, competing with many Burmese Facebook users who see the reporters as traitors.

It is an encouraging sign to see books at opposite ends of serious debates about Burma’s political dynamics being openly sold. But when real debate is increasingly retreating from the commons to an online arena of vindictive and violent posturing, the self-aggrandizement of personal opinion over balance and decency, then what people read in a book becomes increasingly marginal in a post-truth world. The hope is that people will break the imprisoning bonds of their cell-phones, the screen-reality of high volumes of online hate and distortion, and spend more time perusing the richly stocked stores of downtown and re-discover a measure of civility in the democracy of books.

David Scott Mathieson is a Rangoon-based analyst working on conflict, peace and human rights.