Ashley S. Kinseth probes the relationship between social media and conflict and its evolution over the past year.

This post is part of Tea Circle’s “2018 Year in Review” series, which looks back at developments in different fields over the last year.

“In a sea of human beings, it is difficult, at times even impossible, to see the human as being.”

Aysha Taryam, Author of The Opposite of Indifference

When I first found myself working in Northern Rakhine State (NRS) in 2013, I had already begun to observe that smartphones were becoming a global norm, even in the most remote of areas—not only in Myanmar, but around the world. Where I had once so nervously snapped candid shots in rural villages, I suddenly found myself surrounded by villagers nonchalantly photographing and videoing me using their phones. Over the course of a few years, “camera” ownership and use had gone from the purview of the world’s wealthy (in which I include virtually everyone from “developed” nations) to a nearly universal constant—for the rich and the poor—in the form of the cell phone. With that, our mutual camera shyness dissipated, and we (myself and rural villagers) would find ourselves taking turns playing photographer with one another, looking at one another’s shots in a playful and relationship-building exchange: where language failed us, photos brought us together.

In this way, the spread of the smartphone over the past decade at first seemed to me a beautiful thing: democratizing access to technology across the globe, and, as an optimistic activist like myself might hope, enabling—through social media—individuals around the world with the most seemingly distant lives to communicate, to understand one another, and fundamentally, I hoped—paraphrasing Aysha Taryam—to come to see other humans as beings. One might have also dreamed that social media might help to spread real, factual news, particularly in areas where such access was otherwise denied.

With that in mind, it is at this point perhaps worth highlighting some key facts related to the rapidly-evolving use of Facebook as a primary news source in Myanmar. Although in 2014 fewer than one percent of Myanmar citizens had internet access and less than five percent had mobile phones, by 2016 Myanmar boasted more Facebook users than any other South Asian country. Today, more than 14 million citizens (over 26 percent) use Facebook. Many of these users consider it “the only entry point for information,” regarding it as their primary news source and considering postings as actual “news” (with users outside Yangon seemingly less likely to understand that “postings may not be news and could be used to spread rumours”). Indeed, according to one Yangon-based cyber security analyst, “Facebook is arguably the only source of information online for the majority of Myanmar.”

Thus by the time I returned to stay in NRS in 2017, the latter notion I had held—that social media might serve as a platform for the spread of “real news”—had to my mind already been obliterated (since, as an American still reeling from the 2016 election, I could hardly fail to see the role Facebook had played in spreading misinformation in the US). Yet, ever-the-optimist, my earlier hope prevailed: could social media not serve to dissipate the all-too-human tendencies toward dehumanization and “othering”—thus widening the individual’s concept of the “in-group”—and ultimately, to help him to recognize a shared humanity in others?

It was thus with some degree of surprise that, as I resumed working in NRS last spring, I observed some of idiosyncrasies in the way social media was used and viewed in this particular corner of the globe. As a conflict specialist, I was of course well aware of the interethnic tensions surrounding me, and I knew that all foreign organizations operated there whilst tiptoeing atop eggshells, always at the government’s pleasure—or, with the slightest misstep, not at all. Nonetheless, over the past year—and particularly in the lead up to and during the August/September crisis—I still found myself occasionally taken aback, with my hopes for social media’s potential to do good growing increasingly tempered.

At the time I arrived, rumours were already long brewing about the international community’s work in NRS on both sides of the ethnic aisle: that the foreigners gave too much to one ethnic group, and not enough to the other; or that they supported one group’s political interests at the cost of the other. NGOs were thus keenly conscious of the dangers of disseminating branded goods (like logoed t-shirts, pens, and notebooks) that, in many other contexts, the same organizations would happily give out. For in Myanmar—and particularly amidst the fragile peace that barely held in Rakhine State—what might happen if one of those items found its way into the wrong hands, and if a photo were to circulate on Facebook and misrepresent the NGO’s work and intentions? Not only could it hamper the organization’s reputation and its ability to work in the region (or even throughout the country)—but in the powder keg in which we all lived, any misstep or slip of the tongue could prove to be the match to spark a great fire. Foreigners like myself thus relied on local colleagues to keep us in the loop as to how our organizations—and, more generally, the international community at large—were being portrayed on social media, and tried our best to remedy any false rumours about the nature of our work.

In the end, of course, we know that no organization caused the 2017 crisis (though prevailing beliefs about the international community’s work and interests in the region may have played some role in stoking tensions). Nonetheless, social media—and especially Facebook—certainly played a key role in what was to come: for as has now become widely known, in the wake of the August 25 attack on security outposts by a handful of Rohingya militants, hate speech and false information spread like wildfire. In many places, the number of Rohingya militants and their purported affiliation with international jihadist movements was gravely exaggerated, as were the numbers of security personnel and Rakhine killed. Rumours also circulated on both sides that ever-greater dangers were afoot, exacerbating tensions, fanning the flames of violence (as many individuals switched over to a “kill or be killed” mentality), and directly leading many Rohingya to flee.

Meanwhile, on a personal level—although I (like other foreigners) was soon expelled from the region—I remained Facebook friends with many locals, including both Rakhine and Rohingya who I had come to know well personally. I had known many of these contacts to work in various offices together, where—at least from an outsider’s perspective—both sides seemed to get on quite well; indeed, if we had not known better, we might have imagined our small offices and simple, quiet gatherings not to be surrounded by any sort of tensions whatsoever. Without directly witnessing any grievous acts, tense exchanges, or even disparaging words ourselves, it was often easy for foreigners like myself to fall into this mindset: believing most people to be generally good, and—though we all certainly knew the metaphorical matches were simply hidden from us—still reluctant to believe that widespread conflict could truly be sparked at any moment.

In that sense, I do not think I will ever know the full truth about how my local friends viewed one another, as the topic was always taboo. Still, I clung to the hope that—since most worked in development and human rights—they could not possibly harbour secret or blanket hatreds for one another, nor would they fall prey to mass hysteria. Yet as I took my forced leave—and despite my inability to read Burmese—one thing even I could see spreading swiftly on Facebook struck me: the sudden prevalence of the Rakhine flag across the profile photos of my Rakhine friends, which appeared as not-so-subtle code for “Rakhine State belongs to the Rakhine people” (and used, rather perversely, in much the same way LGBT pride flags had been in the US just two years earlier: overlaid on profile photos in celebration of the legalization of gay marriage). How was it possible, I still wondered naïvely, for individuals I felt I had known so well—and who I had seen interact so peacefully with their Rohingya brethren—to now so readily adopt such an exclusionary ethno-nationalist symbol (likely knowing that some may perceive it as a hate symbol, not unlike many perceptions of the Confederate flag in the US), and so prominently for all the world to see?

Tragically, from that point and as we now know, the situation in NRS would only deteriorate. Following my departure, as the pace of attacks on entire Rohingya villages by both security forces and emboldened Rakhine militant groups accelerated (details of which we now know to be horrific), and as the number of refugees fleeing to Bangladesh swelled, viral Facebook posts worked to gravely exacerbate the situation. The original authors remain generally unknown (though, it has been suggested, the Myanmar government itself may have worked to fuel ethnic tensions in the region). Nonetheless, statements by top Myanmar officials—including Myanmar’s Army Chief General Min Aung Hlaing and Aung San Suu Kyi herself (both, it seems, taking cues from the Trumpian “fake news” handbook), along with viral posts supporting these claims—insisted that the stories emerging from refugee camps and the international media’s portrayal of the situation were entirely one-sided. Some viral posts even claimed that it was actually the Rohingya themselves who slaughtered their own brethren, who razed their own homes and crops, and who staged seemingly gruesome photos to garner international sympathy. Meanwhile, other photographs were doctored or misrepresented, shared on social media and accompanied by misleading text intended to stoke fear and further incite violence.

With talks of repatriation looming, many of these same rumours continue to swirl on Facebook today—making refugees’ fears of returning to NRS even more valid, and increasing the likelihood that repatriations would eventually result in further conflict. Most recently, many in Myanmar have claimed that the Pulitzer Prize-winning Reuters’ photographs of Rohingya refugees were staged. Meanwhile, such racist-nationalist vitriol has taken root on Myanmar’s social media not only against the Rohingya, but against other groups, like the once-again-persecuted Christian Kachin. Having perfected its propaganda machine (not to mention military strategies) in Rakhine State—and with little real backlash from the international community—the Tatmadaw appears poised to turn its attention elsewhere, and to allow social media to do much of its dirty work on its behalf: ultimately ridding the country of any “unwanted” ethnic groups.

In retrospect, the immense dangers of social media should have been easy to spot. Indeed, in my own words, “there has never been a more powerful tool for the rapid dissemination of hate speech and racist-nationalist vitriol than Facebook and other social media”; and “historically, one can hardly fail to see the parallels between the current use of social media in Myanmar and that of radio in Rwanda to incite mob violence. The key exception is that social media is by all accounts an even faster, more graphic, immersive, ‘democratic’, and ultimately, dangerous tool for the dissemination of hate speech: perhaps the most significant precursor to genocide.” It is with this relationship in mind that so many civil society groups and multilateral institutions—some in which I myself have worked—have thus long focused on tracking hate speech with the aim of preventing mass atrocities.

Though their work could not prevent this atrocity, groups like these have proven instrumental—as has been reported heavily in recent weeks—in making Facebook and other social media platforms aware of the grave role they have inadvertently played in exacerbating this conflict, as well as the important role they must now play in subduing future conflicts. With respect to Myanmar, at least, Facebook Founder Mark Zuckerberg recently told activists in a personal email that the company has devoted increased resources to tracking and tackling hate speech, including by hiring “dozens” of Burmese content reviewers, by increasing the number of employees working on “Myanmar-related issues,” and by assigning a team to build “tools” to help stem violence in Myanmar.

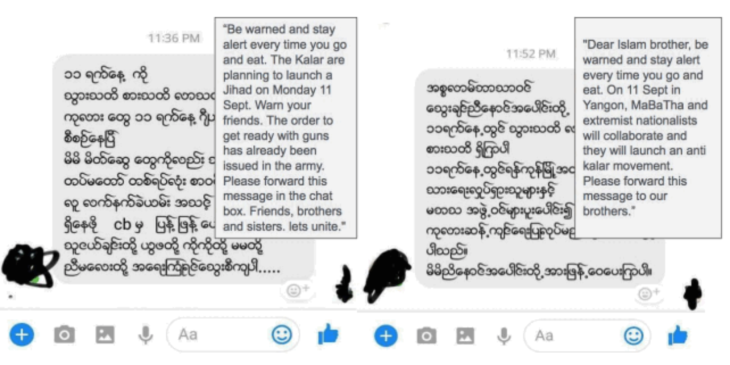

That said, in an April 2 Vox interview, Zuckerberg also held up a certain incident from September 2017—one that has been heavily criticized by civil society groups—as a model of Facebook’s effectiveness in tempering hate speech. The incident referenced involved a chain letter that had spread through Facebook’s Messenger platform, warning Buddhist communities of attacks by militant Muslims—while Muslim groups received similar messages warning them of imminent attacks by Buddhist extremists. According to Zuckerberg, Facebook was effective in swiftly responding to concerns about the messages raised by civil society groups, promptly detecting and removing the messages. Yet according to the groups and other critics, it took the company days after the messages had initially been flagged, and Facebook bombarded with activists’ pleas, before any action was taken. Yet by then, it was much too late: as the groups noted, addressing such dangerous hate speech should be a matter of hours—not days or weeks.

As with so many issues raised in this article, then, the question remains: what is the truth? In Facebook’s case, I’m inclined, perhaps ever-optimistically, to think that the truth falls somewhere in the middle. I do believe that Zuckerberg’s intentions are mostly good, and that looking back, he likely regrets Facebook’s role in the Rohingya genocide. Yet I also believe that Zuckerberg is, not surprisingly, also always looking out for his business interests: seeking to portray Facebook as having done better than it has to quell hate speech, while at the same time committing just enough additional resources to quiet public criticism.

But on this issue, I do not see civil society groups and activists going quietly any time soon: for it is perhaps only within the past year that we have entered a new era when it comes to hate speech propagation, particularly in Myanmar. As stated, never has there been a “faster, more graphic, immersive, ‘democratic’, and ultimately, dangerous tool” for spreading such information. As armed conflicts and political cyber-dramas continue to play out both in Myanmar and around the world, I doubt this is the last we will hear from either hate speech-conscious groups and activists or from Zuckerberg and other social media magnates.

Ultimately, the interplay between modern “leapfrog” technology and increased access to (mis)information, global issues surrounding social media as a platform for fake news/hate speech, and armed conflict pose a very new, and very real, threat to the safety and human dignity of ethnic and religious minorities not only in Myanmar, but around the world. Sadly, my own optimism has been all but quashed: for we see (perhaps more clearly in Myanmar than anywhere else) that social media has—rather than becoming a tool for the promotion of intercultural exchange and human empathy—instead been harnessed for what may perhaps be the very worst human evolutionary trait: that is, our tendency for “othering” as a means of protecting our own “in-groups.” To overcome this tendency, humans must rely on higher-level reasoning abilities, amplified by education and literacy, to reject objectively false conceptions of the group and what it means to be human—and in the end, to put an end to thoughtless dehumanization.

Of course, such higher-level evolution in human thought processes would surely require improvements in global education, which I do not expect to see in the very near-term. In the meantime, Facebook’s devotion of a few more resources to Myanmar is a start, and an important one at that. Nonetheless, it remains to be seen just how much more must be done to stave the relentless flow of false information and hate speech across social media, both in Myanmar and on a global scale.

Ashley S. Kinseth is an international human rights and humanitarian lawyer who has studied and worked on Myanmar- and Rohingya-related issues for over five years. She is also the recent founder of the non-profit organization Stateless Dignity Project, which works to advocate for the safety and dignity of stateless people and families. Prior to this undertaking, she worked with numerous international organizations, including the UN Office on the Prevention of Genocide, The Carter Center, and the International Senior Lawyers Project. She is a graduate of Columbia Law School (JD), the Middlebury Institute of International Studies (MA), and New York University (BA), and is the former Editor-in-Chief of the Columbia Human Rights Journal. She has previously published on Rohingya-related issues, including in Al-Jazeera and here at Tea Circle, as well as on Cambodian post-genocide reconstruction and peacebuilding efforts.

Like This Article