Lili Kyawt (pseudonym) reflects on experiences of trauma shared by different generations.

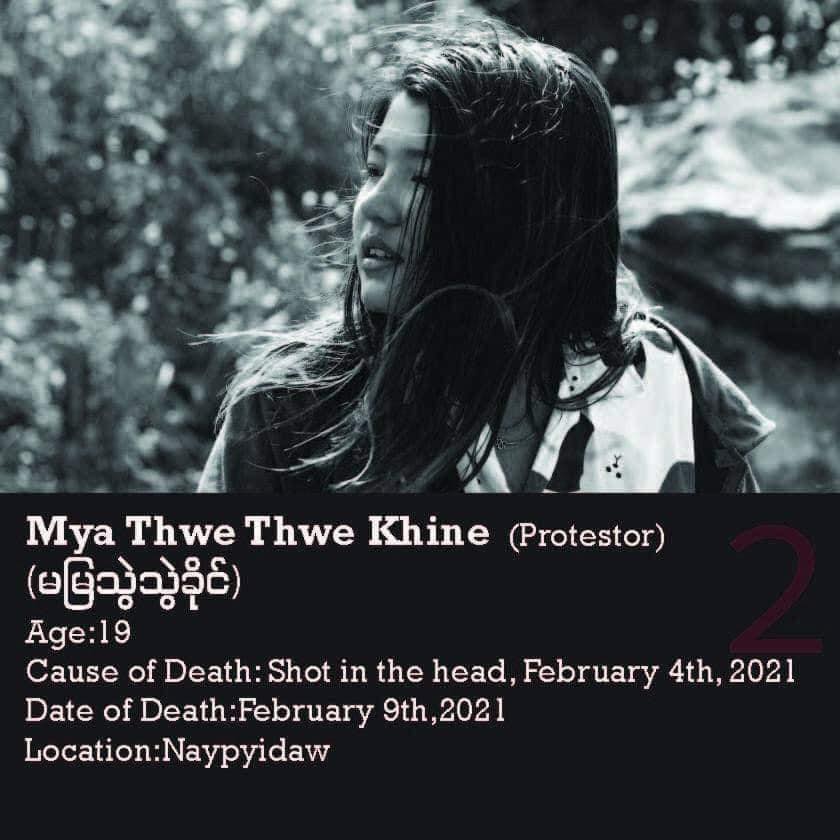

When I got up on 1 February, I heard about the coup in Burma, my country. I tried to identify an assortment of feelings: anger, despair, distress, sadness, hopelessness. None of them seemed to fit precisely what I felt. Since I am not in Burma, I rely on Facebook, the communication channel most Burmese use for information, to stay informed. With those unnamable feelings in my chest, I started checking Facebook almost hourly to catch up with the ongoing situation. When a 19-year-old girl died, the first death of the protest, I could finally name the assortment of emotions I was feeling – trauma. A few years ago, a former political prisoner told me the whole country was experiencing trauma because of the violent suppression of resistance over five decades. Her words now came back to me as I tried to understand the emotions running through me.

We are re-experiencing the collective trauma of living under the grip of the military. Every day the violence against protesters escalates and reminds those of us who lived and grew up under the military regime and who witnessed many violent crackdowns since 1962, of “the dark times.”

I was born two years after the coup in 1962. I remember talking with my friends about politics and rumours we heard from adults, when we were about ten years old. Had Ne Win died? How much we children and the adults around us wanted him to be gone, the former dictator. My overriding memories of growing up in Burma under the military dictatorship involve a sense of lacking – of lacking necessities, and above all lacking rights and freedom. Economic struggles, censorship, martial laws, fear of the military and people associated with them; these were a big part of our everyday life. In the backdrop, there were ongoing wars with various ethnic groups. I can still recall watching tanks drive through our township to suppress the student demonstrations in 1974. The next day, we heard many young people had been killed or arrested. The atmosphere was full of fear and suppression, and it was suffocating. Then in 1988, the military killed thousands of people during a massive popular uprising for democracy. My mother went into depression in 1988 at the loss of life she witnessed. This is etched deeply in my memory.

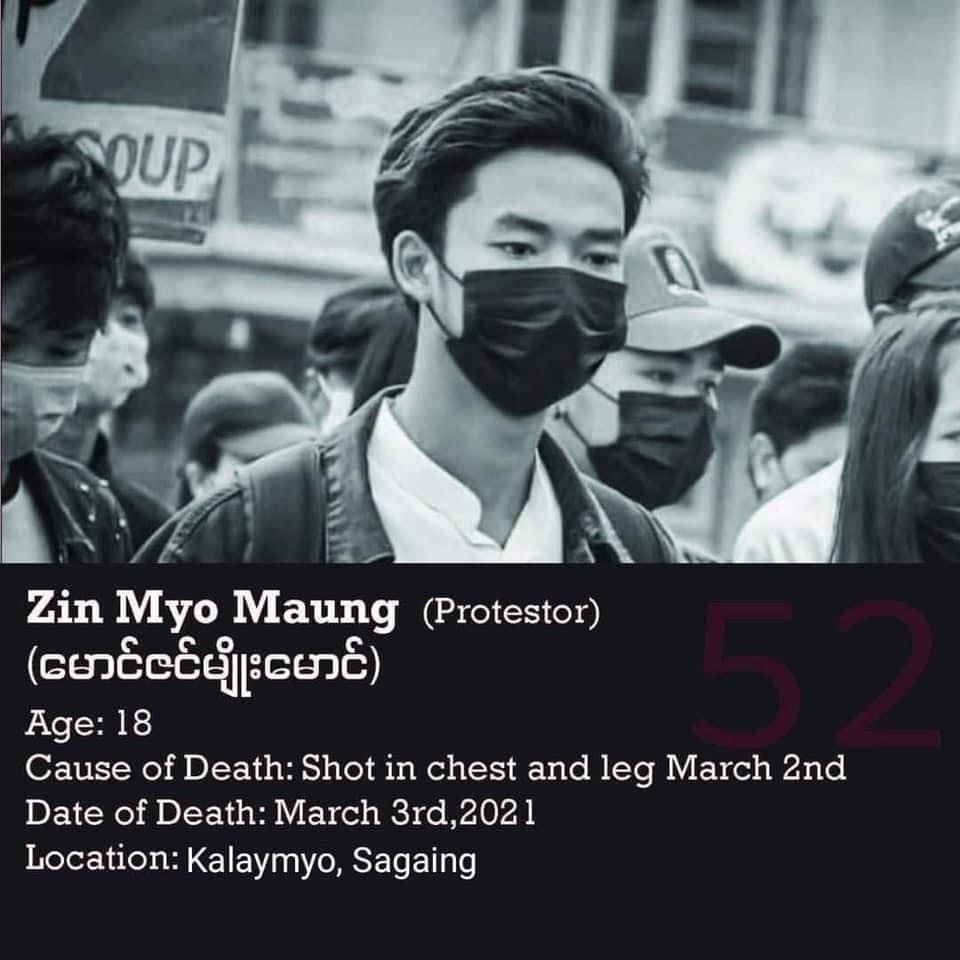

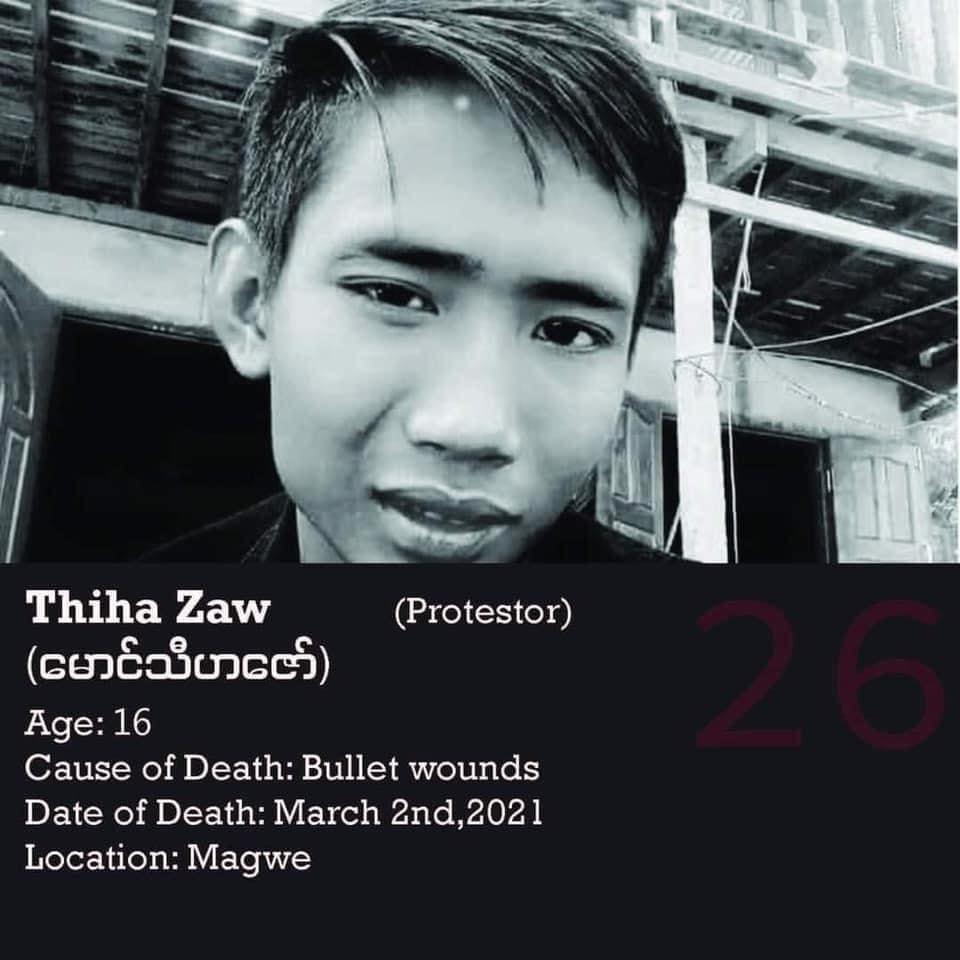

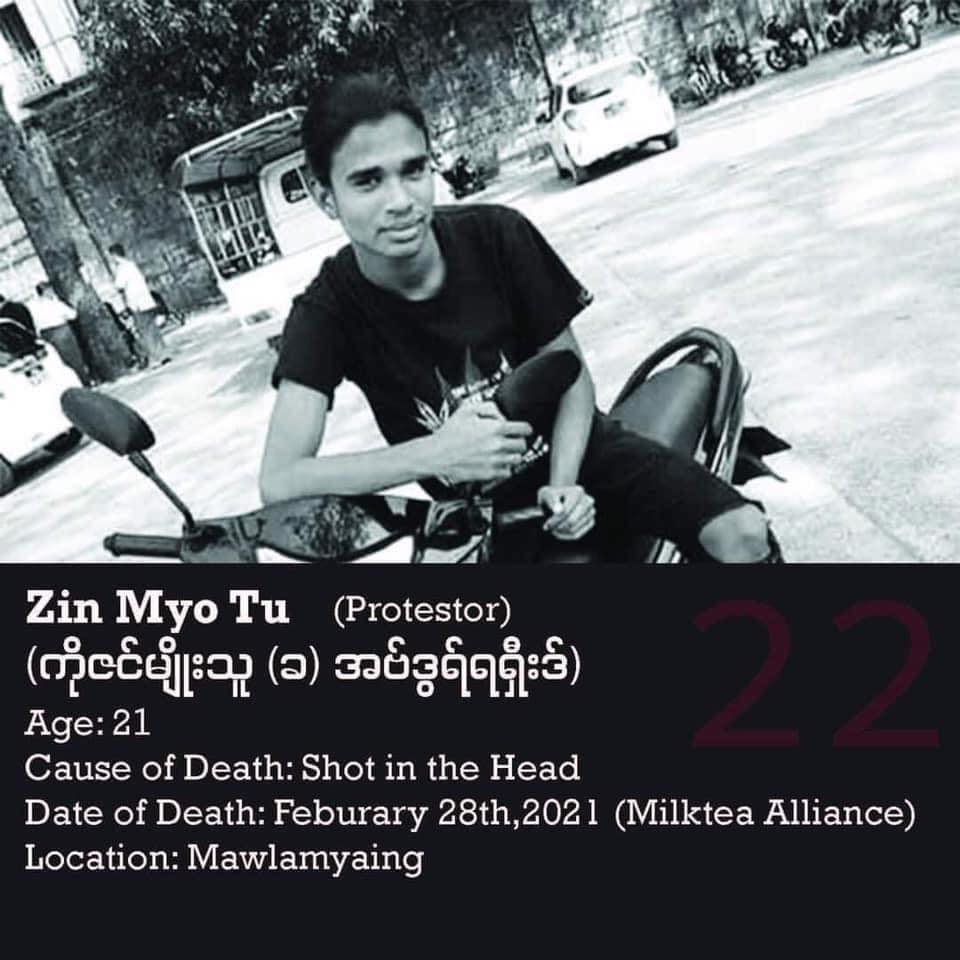

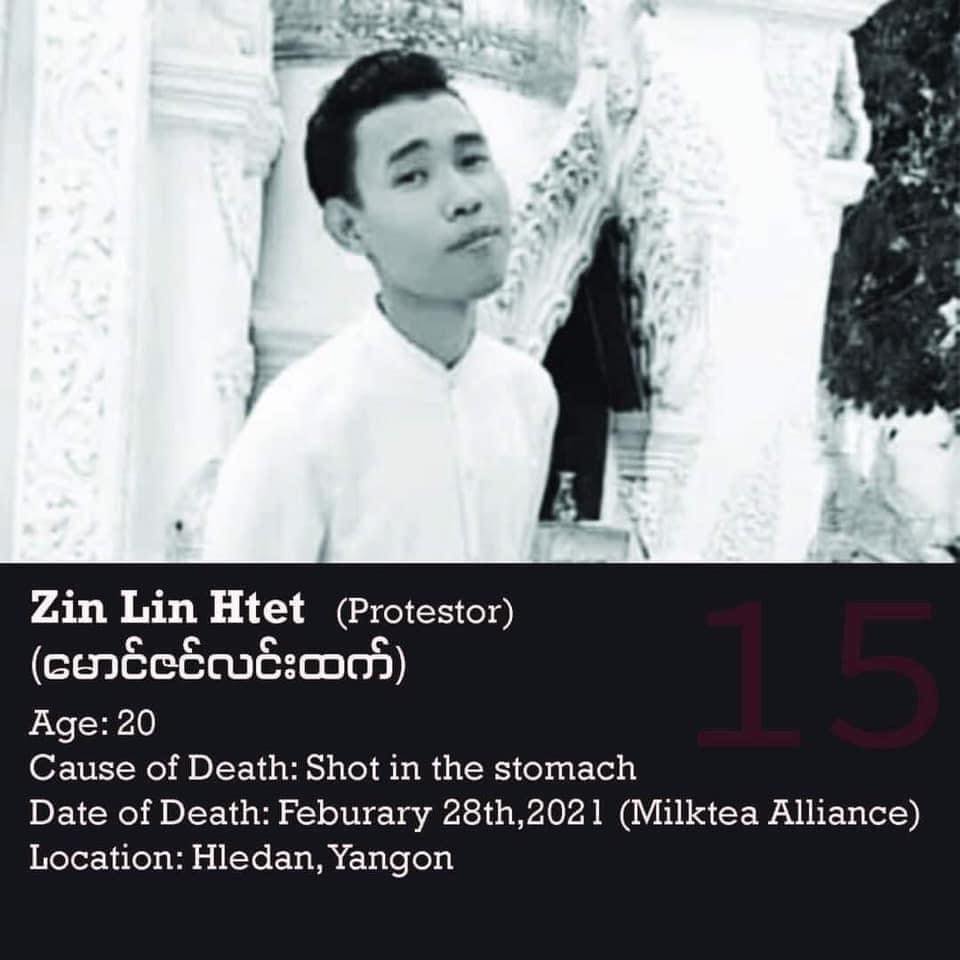

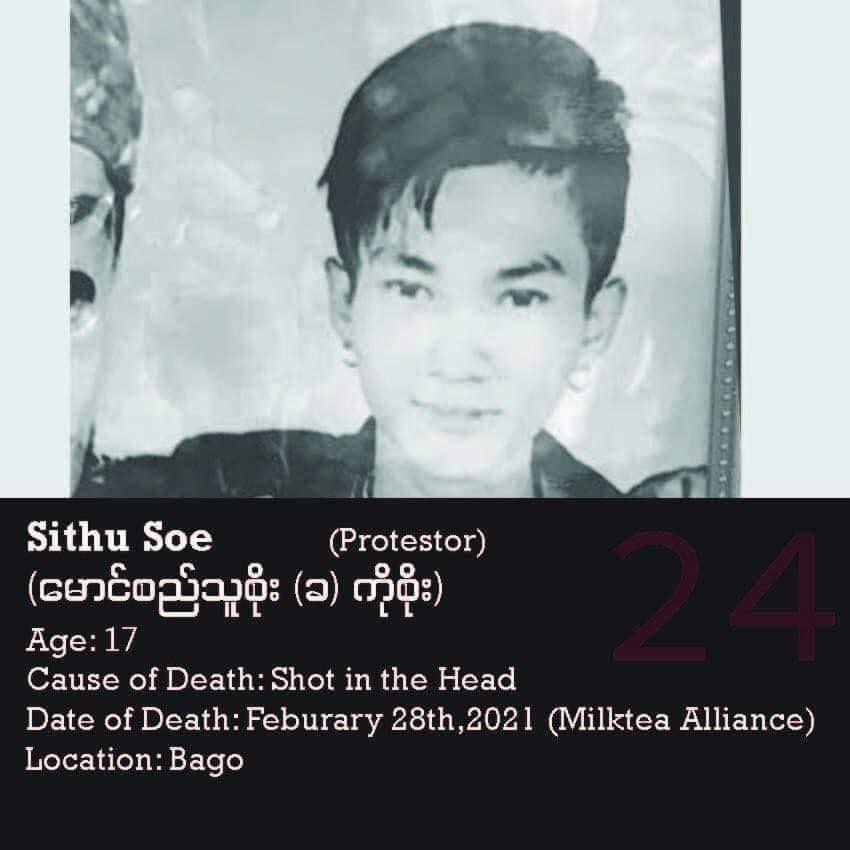

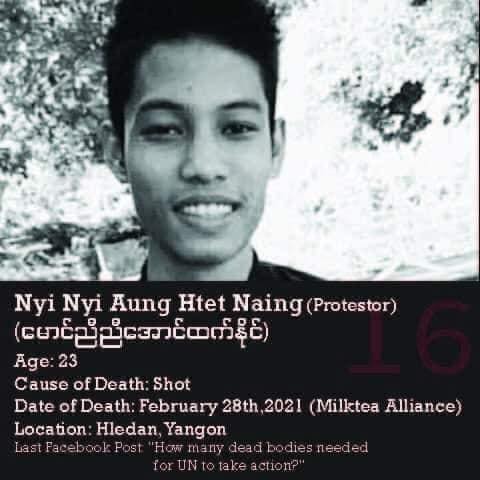

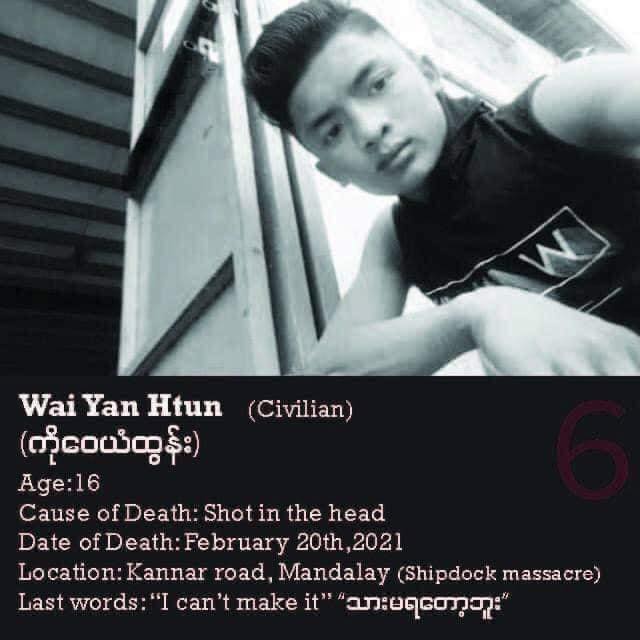

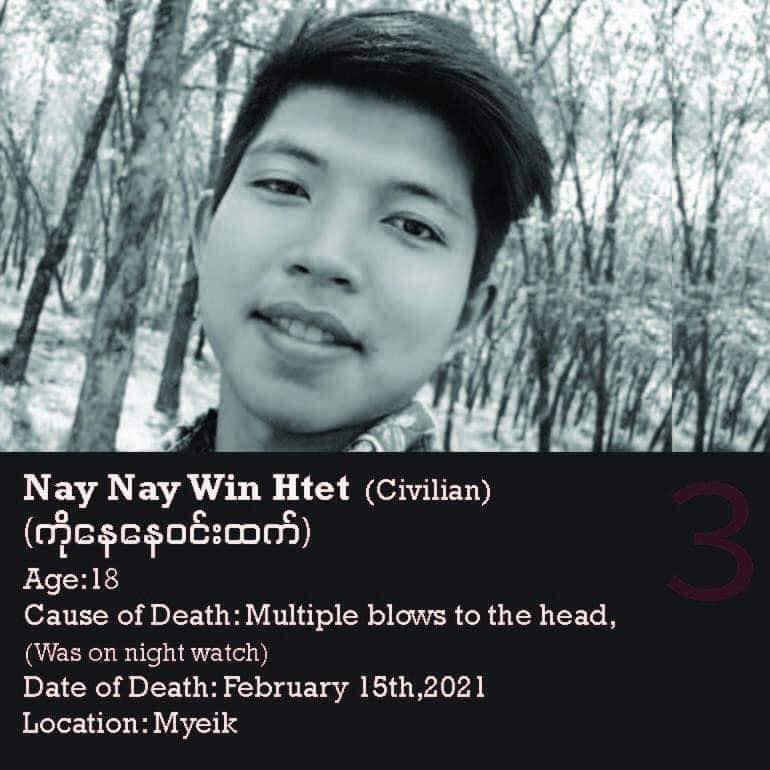

History has shown us again and again that it is always the young people who fight back, and now like before, they can be killed, beaten, tortured, raped. Still, these young people go on and take the front line. Now in 2021, Burma is a different country, but it is still beset by endless political, social and economic problems. Despite these problems, people have some freedom and hope, and communication with the outside world. There is also the widespread use of social media, which we didn’t have access to in 1988. Hence today’s young people, Generation Z, live in a very different political, social, and economic context. However, like many generations before them, they are the ones who dare to start the fight back and sacrifice their lives. The pain, sadness, anger, and anxiety of the families of those young people killed and arrested are unfathomable.

Many people are saying that the revolution is close to victory. I want to believe that the people will win in the end, but at this point, it is not easy to see how the whole debacle is going to unfold. How do you fight an institution that does not hesitate or express remorse about using any weapon available to kill their own people—who are simply asking for their rights to be respected?

People, especially Generation Z, persist despite the violence. On 3 March, Burma mourned the death of Kyal Sin, a 19-year-old girl who got shot in the back of her head. The words on her T-shirt said “Everything will be OK.” She left a note asking for her organs to be donated if it were not possible to resuscitate her.

I felt devastated at the death of Kyal Sin and other youths on 3 March. However, it was seeing an emotional video posted on Facebook by a young woman, and recognising her own trauma, that led me to write this piece. In the video, the young woman films herself narrating her experiences of helping protesters on the frontline. This first-hand account is a plea for others to understand the violence that protesters face every day.

This young woman has been helping protestors to flee from police violence. She repeatedly saw young people being brutally beaten up by the police. She had been using her car to block the road to delay the police vehicles so that she could assist the protesters to safety. It had been getting more and more difficult for her to do this because fewer people were turning up for the protests. The increasing use of tear gas, stun grenades, and live bullets emptied some of the main streets, and it was easier for the police vehicles to get through quickly to attack the protesters. Sometimes the makeshift roadblocks put up to deter police forces or police cars from passing through accidentally blocked her from reaching protesters. Other times people taking videos of the protests ignored her request to let her car pass through. Not being able to get through to the people she intended to help, and seeing police beat up her colleagues brought her to breaking point that day. She repeatedly said, “They asked the kids (protestors) to put up their hands on the heads and then they relentlessly beat them on their backs.” This broke her heart more than anything else.

This woman knows she might die helping them, but she puts herself at risk to rescue the core young protestors. She wants more people to participate in protests to fight against the military and shield the front-line protestors. Since 1 February, she has hardly slept and has only eaten one meal a day because she is too tired. For her, the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) is not helping unless everybody participates in the protests. Like most young people, her fear of losing out to the military is far greater than her fear of dying. Her emotional response on Facebook to those criticizing young protestors for confronting the police instead of having small protests near their places of residence, and her plea to people, gave me a glimpse of what young protestors are going through.

There are good days and terrible days in the over-a-month-long ongoing protests. On good days, most protestors get away unscathed, inspired, hopeful, and with renewed aspirations. On terrible days, some get killed, wounded, arrested, but the people do not give up. Every day, they come out to protest the coup. They are determined to make sure the military goes down. That’s when you can see the best of Burmese people, their resilience. The younger generation fights with creativity, resilience, and humour that keeps them going even though they are putting their lives on the line. You can see messages or posts on Facebook that encourage unity, such as “we can have different opinions but we are not divided.” People set aside religious and ethnic tensions to fight the common enemy – the military, and, by doing so, they have more compassion and understanding of years of atrocity and violence directed at ethnic groups, including the Rohingya.

I have learned from a good friend of mine, a survivor of violence, that post-traumatic growth and resilience emerge in the aftermath of violence. Dealing with trauma is not a walk in the park. There are good days and bad days. Bad days can take you to the edge, but resilience can bring you back to embracing life. Sometimes it comes from inside. And sometimes the help from outside is necessary to keep on going.

More than ever, people in Burma need every possible form of assistance from the international community to continue their long struggle. The UN, ASEAN, China, Russia, India, Japan, and other countries need to take action. Every country can take action if they take their mind off trade, regional competition, and geopolitical influence. The Burmese people have shown their spirit and resilience in the face of the violent suppression by the military. Day by day, people in Burma realize they cannot depend on outside help, not even the UN. Regardless, they are determined to continue their revolt against the military. The protests have grown so large and spread across the country that they have become transformed into revolution. Even if the international community fails to help Burma, the “Early Summer Revolution” (named by the protestors) will go on.

People of Burma have experienced collective trauma, but they have tremendous resilience, and the world needs to stand by them.

The following is an English translation of a post by a poet that was shared on Facebook:[1]

I am afraid of mornings.

When he wakes up, he goes straight to the bathroom, has a shower, changes his clothes, picks up his bag, and gets ready to go out of the door.

He doesn’t even notice the breakfast I prepared for him.

I ask, Where are you going today?

He used to tell me whether he was going to Hledan, Sule, Sanchaung, or Bargyar.

Now he only says where the protest is.

I warn him they are going to shoot today.

He said they are shooting every day. Don’t spread that kind of talk. Instead of 100 people, only 50 will come to protest. Don’t make me afraid. It’s not the time for fear.

Looking thin and sunburned, no gun, no bullet, just a backpack and the three fingers salute.

He: Don’t keep calling me.

He goes, and I go. I can exhale when everybody comes back home in the evening.

Exhausting days since the coup.

I have absolute empathy for the fallen heroes and their families. Salute to them!

[1] Little information about the author, including his real name, is available online.

Lili Kyawt (pseudonym) is from Burma and a part-time lecturer based in Japan.