Charlie Artingstoll, Maha See, and Eolene Boyd-MacMillan explore a range of mental health challenges for Myanmar and identify where action is needed to increase mental health and psychosocial support.

For a country of 55 million people, in the midst of the longest-running civil war in the world, with a population suffering high levels of trauma and depression and a gutted public health system, the number of qualified clinical and counselling psychologists actively providing therapy and counselling is no more than ten. The proportion of the population with mental health problems who are not receiving any treatment is estimated to be over 99.5%.

The need for mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) in Myanmar is difficult to overstate.

Complex factors on multiple levels have interacted over decades to perpetuate this situation in Myanmar. The current law on mental health absurdly remains the 1912 Lunacy Act. Since independence in 1948, Myanmar has had one of the lowest expenditures per capita on healthcare in the world, and despite some improvement during the 2011-2021 movement toward democracy , chronic underfunding has restricted what little mental health care exists to biomedical approaches including psychopharmaceuticals and electroconvulsive treatment. The 2021 coup, with its ensuing violence and repression, has made the situation immeasurably worse. Those not experiencing direct trauma often suffer second-hand trauma from exposure to violence in grizzly detail on social media that lack any filtering or moderating protocols.

As a result, a study completed at the end of 2022 found that one in four people in Myanmar experienced moderately severe to severe levels of depression, more than twice the levels found in 2008 in neighbouring Thailand (whose 1037 reported psychologists are nonetheless viewed as a severe shortage). Another study carried out in 2021 in Myanmar disclosed consistently high rates of probable anxiety and depression (60.71%).

While counsellors, psychotherapists, and clinical psychologists cannot prescribe medication, they can offer behavioural, relational, and trauma therapies that often provide safer, more effective and sustainable relief than pharmaceutical interventions. The vast majority of psychiatrists in Myanmar do not offer psychotherapy or counselling.

The institutional infrastructure, regulation, and oversight of mental health services and programs remains compromised or simply absent inside Myanmar, and international collaboration with the current regime is not an option. So the only current solutions involve short or medium term (counted in days or weeks rather than years) projects offered by the NGO/foreign aid sector, such as brief training sessions or psychological first aid courses.

There are reportedly no investment targets for mental health beyond the short term. These are often one-off projects, and medication management, even by large international organizations that have supported Burma/Myanmar over the decades. No universities in Myanmar currently offer certificates, diplomas, or degrees in clinical psychology or counselling.

The handful of Burmese students who manage to study abroad thanks to international scholarships can never fill the treatment gap. Even applicants who can pay their own fees face few options in the ASEAN region. For example, there exists only one English-language counselling program in Thailand and only a few in Singapore. Such program rarely, if ever, reference the Myanmar context or account for Myanmar indigenous cultures.

Without longer-term capacity building, Myanmar will not develop adequate public mental health support and services. Foundations must be laid for the large-scale equipping of indigenous mental health professionals from Myanmar and the surrounding region, supported in higher education institutions by ongoing research and professional development across mental health areas and specialisms.

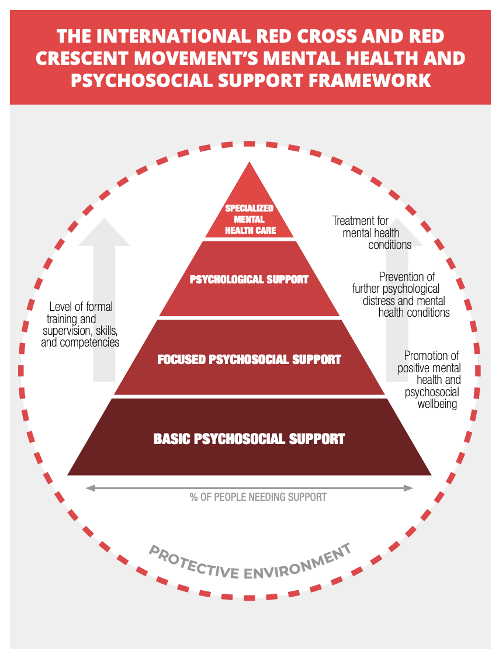

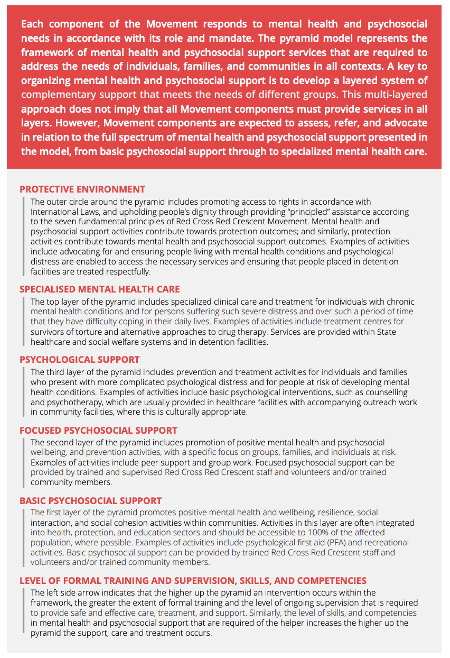

The widely used MHPSS pyramid of care diagrams four layers of support for varying levels of mental health needs and care provision.

If properly funded and structured, short-term training may provide temporary support for those on the bottom two levels. Prompt attention to milder cases of mental ill health, for instance, can mitigate against the development of serious symptoms. Similarly, ongoing training, resourcing, and support of community leaders such as teachers and healthcare workers can begin to address intergenerational trauma among children, young people, families and communities That said, all formal mental health support of any type or length needs to be supervised, monitored and regulated.

Each refugee or internally displaced group has a unique profile of protective and risk factors based on their respective histories of conflict and ongoing conditions. But given the grave situation in Myanmar and for the Myanmar diaspora in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore, it is not unreasonable to estimate that tens or even hundreds of thousands in country and border camp areas are living with severe, chronic mental distress that requires expert support from trained clinicians at the top levels of the MHPSS pyramid of care. Anything on Level 3 requires professional (i.e., a Masters or above) supervision, and Level 4 requires clinical professionals. The referral of serious cases up the chain to appropriate care cannot work when specialists or community-based providers are not present or have no capacity to take on new cases. Conversations with groups directly involved in the ongoing crisis, such as human rights defenders and journalists, indicate that there is a critical need for specialist mental health services, including for those experiencing second-hand trauma.

First-hand reports[1] from the Myanmar diaspora in the Thai border town of Mae Sot, for example, speak of increasing demand for quality social services and case management. Almost all potential clients in Mae Sot have experienced trauma – even gender-based violence or torture in prison – and many are likely to require mental health services well beyond psychosocial support. But the reports question the credibility of existing counsellors and MHPSS services, referencing the large increase in the number of brief training projects being offered. One individual reports that practically every NGO or group is providing some form of training because that is where the funding is: short-term projects with minimal supervision or monitoring.

Due to the lack of regulation of mental health provision, those with short-term training (days, weeks, or months) and very little, if any, counselling experience are able to offer training courses and issue qualification certificates. Since 2021, short (e.g., 20-60 hours total), often online, courses in mental health have grown in popularity. In contrast, clinical psychology and counselling psychology degrees demand 1,000-1,500 hours of higher education level input, followed by 1,500 hours of supervised practice.

Regardless of the availability of trained psychologists and institutional frameworks, if people are ignorant, dismissive ,or distrustful of mental health services, then significantly improving the situation becomes almost impossible. Simply put, seeking professional support will not even occur to many or most who would benefit.

Effective efforts can be made to inform the public about mental health while addressing the barriers to service access. Well-structured online campaigns of outreach and education could work with some populations, notably among Myanmar’s 22 million social media users (mostly youth). Indirect social contact, such as video content, can also effectively combat widespread stigma against psychological therapies.

Older adults who are not on social media are more likely to be reached through in-person strategies that build relationships based on trust. In Myanmar culture, mental health stigma can be a collective phenomenon. Individual services are never merely individual and the development of outreach or educational programs that counter stigma often ‘takes a village’ built on longer-term relationships and training of community leaders.

In a country as diverse as Myanmar, raising mental health awareness requires culturally relevant collaboration and coordination with local people, especially since a large majority of the population live in rural areas, are members of ethnic minority groups, or primarily speak one of Myanmar’s 135 ethnic languages.

This linguistic diversity necessitates sensitivity to wide variations even within communities in terms of levels of literacy, linguistic formality and style, and the relative acceptance of Burmese, which is sometimes viewed as the language of the oppressor. That said, given the lack of MHPSS funding for ethnic language speakers whose exposure to poor health, poverty and trauma is often high, the relatively low cost of translation makes it a worthwhile, cost-effective approach, particularly when targeted in audio or audio-visual format at groups that most need support.

In short, we believe that systematic and sustainable development of the mental health landscape in Myanmar will require multi-level, multi-sector, multilingual, cross-institutional partnerships and collaborations in Myanmar, the ASEAN region, and beyond.

Locally-led collaborations with indigenous actors will need to form an oversight committee that can write, develop, and implement a code of conduct for organizations and individuals working in the mental health space, setting quality standards for service provision and clarifying the limitations of different MHPSS activities, using the pyramid of care as a guide. Led by indigenous partners, these efforts may aim at future engagement with the National Unity Government (NUG) to create a sustainable roadmap for improved provision of services over the long haul.

In terms of supply, indigenous actors need to develop partnerships with regional universities and other bodies able to support the creation of faculties equipped to teach students from Myanmar and countries in the wider ASEAN region that face similar mental health challenges. The resulting higher education programs and qualifications will need to be coordinated with existing providers to ensure that critically-needed specialist support is offered to the most vulnerable populations, such as IDPs and victims of torture or violence. Finally, there is an acute need for the development of more rigorous online courses with adequate, ongoing supervision and monitoring by qualified, experienced professionals.

From the demand side, Myanmar has a critical need for collaborations with indigenous actors to develop multi-media, multi-language public information campaigns that increase understanding of locally identified and experienced mental health issues. Campaigns should be based on evidence from culturally-sensitive MHPSS models that account for variations in needs, risks, symptoms and thresholds for disorders. In keeping with a 2019 study on trusted sources of information in Myanmar, they should prioritize content from well-coached celebrities and influencers who are a vital source of information for the public and should include video content, social media campaigns, websites, resource development, and group workshops with key community leaders.

All these resources must be developed in consultation with teachers and healthcare workers who can identify priority needs in the children, young people, families, and older populations they encounter on a daily basis in schools and other community-based facilities.

The woefully ineffective response by international donors to the realities of the mental health crisis in Myanmar will have adverse effects for generations to come. It has been described as a band-aid strategy focused on short-term Psychological First Aid (PFA) courses that train non-specialists to assess mental health needs and refer patients to specialist care – which is almost always unavailable.

Such courses are necessary but far from sufficient; they can only be useful as part of a wider response. Ultimately, fully-realized short, medium, and long-term solutions will require PFA, social services, further training on evidence-based therapeutic approaches, and oversight in terms of clinical and institutional supervision.

Those providing mental health services need to be trained and accredited. As with any medical doctor, they must have an education and a licence that correlate to the level of care. In practice, this typically translates to at least a Master’s degree in counselling, clinical psychology, or clinical social work from an accredited higher education institution. Unfortunately, basic accreditation or standards in Myanmar do not exist, nor do safeguarding and oversight, nor even restrictions on who can provide mental health support.

As a result, a recent 2024 survey of Facebook ads in English and Burmese has revealed a high number of offers of mental health services and training from sources without evident qualifications. In comparison, a similar investigation from 2017 found five clinics offering counselling and psychotherapy provided by professionals with a minimum of a master’s degree.

None, however, offers specialist training that can address the needs of people suffering from trauma; and just as someone with a basic first aid course cannot perform surgery, individuals with only PFA courses should not administer mental health support to those with serious mental health problems. Ultimately, without ethical and institutional safeguards, this practice is dangerous.

Organizations must ensure that their training is provided by qualified, ethically responsible professionals who clearly outline the limitations of the courses they offer. At a minimum, those who complete the training must clearly understand and communicate what help they can – and cannot – provide.

In a context with an adequately functioning government, international donors would be justified in focusing on emergency PFA—as they successfully do in many LMICs (low and medium income countries)— to plug gaps and provide immediate results through short-term project timelines. However, the current situation in Myanmar is far from functional and the usual roles are not being fulfilled by a legitimate Ministry of Health in the de facto government or by multi-sector professional oversight boards.

Consequently, grant-dispersing entities and NGOs that want to have the greatest impact and ROI (return on investment) must look to address the bigger gaps in care by incorporating medium and long-term planning into their approaches. The time required for adequate, professional training of counsellors and clinical psychologists need not dissuade funders from contributing to the development of long-term resources and platforms. They will be laying a solid foundation for a future with the kind of well-integrated physical and mental health care system that, according to the WHO, is essential for all health and wellbeing.

The current situation represents an opportunity to strategize and create something new with long-term benefits for Myanmar and the wider region. If one issue stands out from the current mess, it is the need for the in-depth capacity building of mental health professionals. Aspiring or counsellors-in-training must have access to the education and training required to serve the specific mental health needs of Myanmar.

Given that there are fewer than ten individuals who have the experience to properly train such mental health professionals, a transitional period will be required while increasing the number of qualified frontline mental healthcare staff and putting in place supervisory and monitoring processes.

One sustainable solution is the creation of counselling training programs that provide committed learners with graduate-level certificates and diplomas based on rigorous evidence-based theoretical and practical training. That this does not exist in Myanmar, or even in English at many regional universities, severely hinders mental health support and care capacity by denying would-be counsellors access to the education required to serve the mental health needs of the country.

This was the concept behind the founding of the Myanmar Clinical Psychology Consortium (MCPC) in August 2017. Although small in scale, with many donating their time without payment, the MCPC runs the only 16-month graduate level program developed in Myanmar. It has awarded graduate diplomas to 18 alumni in clinical psychology, 11 of whom have been accepted to a Masters or equivalent level programs abroad through Australia Awards, Chevening, Fulbright, and other scholarships. Some MCPC alumni plan to pursue doctorates in clinical psychology when funding becomes available. Others have returned physically or virtually to the region to provide mental health services.

MCPC also provided in-person continuing education classes on clinical and counselling psychology topics by experienced, qualified instructors from around the world to over a hundred learners in Myanmar pre-COVID. Discussions are now underway to house this certificate and diploma program in a reputable, committed university in the region, and thereby, extend the programming scope to the degree level, but this urgent need requires support from donors, funders, and higher education partners.

It will take many such programs and considerably larger sources of long-term funding, but if Myanmar is ever to emerge from this mental health crisis, it will need to look forward to a time when some semblance of normalcy returns to the country’s healthcare system. We need to train new generations of professionals who in due course can provide competent direct services and ‘pay-it-forward’ as mental health teachers and leaders in Myanmar.

Charlie Artingstoll runs Sin Sar Bar — a social change organization in Myanmar. His work focuses on taking important ideas and concepts and finding creative ways to communicate them to the general public across multiple channels and also multiple languages. In the past, he has run projects on a wide range of issues: landmine awareness, COVID-19, domestic abuse, drug dependency, and other social issues. Before starting Sin Sar Bar, Charlie worked in the development sector, working for both microfinance and alternative development programs for opium farmers. He has lived in Myanmar for nearly 10 years and has produced a number of articles and interviews on various topics in both English and Burmese.

Maha Y. See, PsyD in Clinical Psychology, is an educator, trainer, researcher, supervisor, mentor, program director, and direct service provider in Myanmar, Thailand, Singapore, and San Francisco, working alongside his team of mental health care providers. His work centers on minority populations across international and cultural boundaries. Beginning in 2006, he worked with refugees and asylees from Myanmar, focusing on trauma and protective factors. Maha has been studying Myanmar mental health issues for 18 years and founded the Myanmar Clinical Psychology Consortium (MCPC) in August 2017 in Yangon, Myanmar. He can speak, read, and write in Burmese.

Eolene Boyd-MacMillan, PhD, is Convenor, Myanmar Desk, Cambridge Refugee Hub, Centre for the Study of Global Human Movement; Senior Research Associate, Co-director IC Research, Co-Founder IC-ADAPT Consortium, Department of Psychiatry; and Member, Cambridge Public Health interdisciplinary research centre, University of Cambridge. A social psychologist, she works within a trauma-informed public mental health promotion – resilience and wellbeing framework. Current research includes reactions to social exclusion and discrimination among young people with diverse political commitments, ethnicities, and cultures across four countries; the supervision of an IC-ADAPT intervention during a pilot study in three contexts (schools, community centres, and NGOs); and the relationship between resilience and resistance among frontline healthcare workers. She contributed the social and emotional learning (SEL) component to the UNICEF-Cambridge Learning Passport (Boyd-MacMillan and DeMarinis, 2020, SEL HIgh Level Framework; and Cambridge University Press & Cambridge Assessment (2020). ‘Section Four: Mental health, psychosocial support and social and emotional learning’, Boyd-MacMillan and DeMarinis, pp.56-90, The Learning Passport: Research and Recommendations).

Notes

Like This Article