Rosalie Metro looks at multilingual classrooms on the Thai-Myanmar border.

Translanguaging can be defined as using all of our language resources to communicate, instead of relying on just one language (Freeman & Freeman, 2018). This term has gained prominence in academic literature about education in the last decade, but it’s also something that teachers on the Thai-Burma border have been doing for much longer. It’s natural for people in multilingual societies to switch among various languages in the same conversation or even the same sentence. However, too often, teachers and students have not been allowed or encouraged to translanguage in the classroom. They have been told that in an English class, students and teachers should only speak English; or if the textbook is in Burmese, only Burmese should be spoken. This is a missed opportunity for learning.

In July 2024, I facilitated a workshop for a group of migrant English teachers from Myanmar in Mae Sot, organized by a local community-based organization. These teachers taught different ages and levels of students, but they had one thing in common: all of them spoke multiple languages, although they had chosen to teach English, or been assigned to do so.[1] I wanted to help them take a strengths-based approach, or an assets-based approach (Colorín Colorado, n.d.) to their own language capabilities. This meant working with the skills that teachers already had – including their knowledge of multiple languages – instead of starting from skills that they seemed to lack.

To do that, I shared some history about second language acquisition theories. In the past, many people believed that students would learn a new language better if they only spoke that new language, and stopped speaking other languages in the classroom or even at home. This is “subtractive bilingualism,” or the idea that there is limited space in our brains for learning language. But in fact, people learn new languages better when they maintain and develop the languages they already speak. We don’t have to worry about running out of space in our brains. This is called “additive bilingualism” (Minshew, 2020). In Myanmar, as well as in the US, subtractive bilingualism has commonly been practiced. Children have been punished for speaking their home languages at school, and parents have been encouraged to speak the only dominant language (Burmese in Myanmar, or English in the US) with their children. Therefore, many families have painful histories of languages lost and suppressed.

Learning a foreign language, such as English in Myanmar, can be especially difficult, since most students have few chances for immersion. Nonetheless, even an hour of English immersion can be overwhelming for a child displaced from their home by war and forced to attend a school where they struggle to communicate in any language with their teacher or peers. This is a situation where translanguaging can be beneficial.

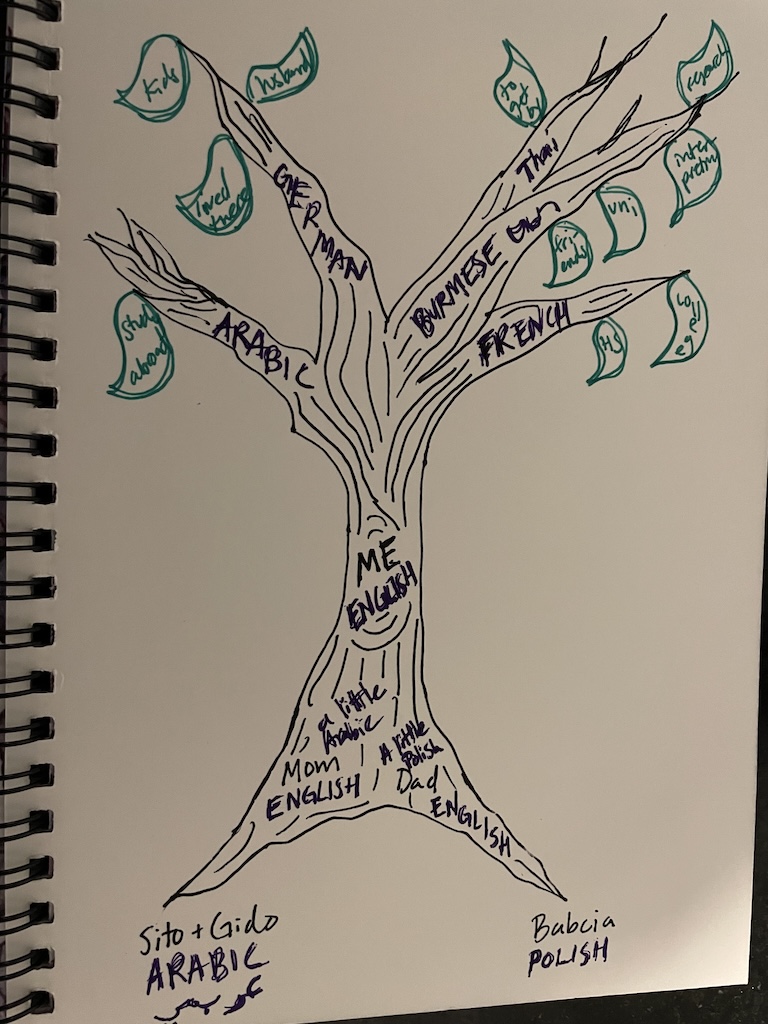

I encouraged the teachers to reflect on their capabilities by having them sketch “language trees” showing all the languages they could speak or read. The deepest roots of the tree are the languages that grandparents or older relatives spoke. Roots closer to the surface are languages spoken by parents or caregivers. The trunk of the tree is our own first language(s) or mother tongue(s), and the branches represent languages that we have learned throughout our lives.

When the teachers created language trees, they included languages such as Burmese, Karen/Pwahkanyaw, Karenni, Thai, English, Japanese, Chinese, and Korean. If they used a language often, they added a lot of leaves to that branch. If a language was suppressed by their schools or communities, a branch might be cut off or the leaves on it might wither. Some teachers added branches for languages they wanted to learn, which had no leaves yet.

I explained that translanguaging was like jumping from branch to branch of our language tree, and nourishing the health of the whole tree, not just one or two branches. We don’t have to let some branches wither and die if we want to sprout new leaves on a new branch. We don’t have to leave behind our languages and identities in order to grow.

The teachers could understand this concept easily, and they shared examples of how they already used translanguaging. For instance, although their textbook was in the “target language” English, they might use Burmese or Karen as a “classroom language” to explain a grammar concept or an unknown word. Or, one student might explain instructions to another student in Karen, after hearing the teachers’ instructions in Burmese for how to play a game using English. Teachers created vocabulary lists in multiple languages. They used “comprehensible input” strategies by buttressing spoken and written communication with images and gestures.

Conversely, the teachers noted that they used only English when they wanted to challenge older or more advanced students, or when encouraging less experienced students to memorize simple phrases. They used a classroom language to help establish strong relationships with students and build classroom community, for classroom management and discipline, and when having meta-level discussions with students about how class was going. They were strategic about what language to use, and they were flexible in switching among languages depending on the situation. The workshop helped them to see translanguaging, which they were already practicing, as a robust pedagogical method.

Teachers also explained some challenges they have encountered with translanguaging. Sometimes they don’t share any languages with their students, and communication is quite difficult. Or, when relying on students to translate for each other, they have no idea whether accurate information is being conveyed. If they aren’t intentional about grouping students, some might rely too much on their same-language peers, and learn little of the target language. Translanguaging takes time, but teachers have to follow a strict timetable of topics whether students have understood or not. Some languages might not have standard written scripts, which can make it more difficult for students to transfer literacy skills as they are learning a new language.

Most crucially, many teachers are in survival mode, coping with low salaries, classes of over fifty students, flooded school buildings, ongoing violence, and accumulated trauma for themselves and their students (Carey et al., 2024), so they may not have the bandwith to focus on effective translanguaging.

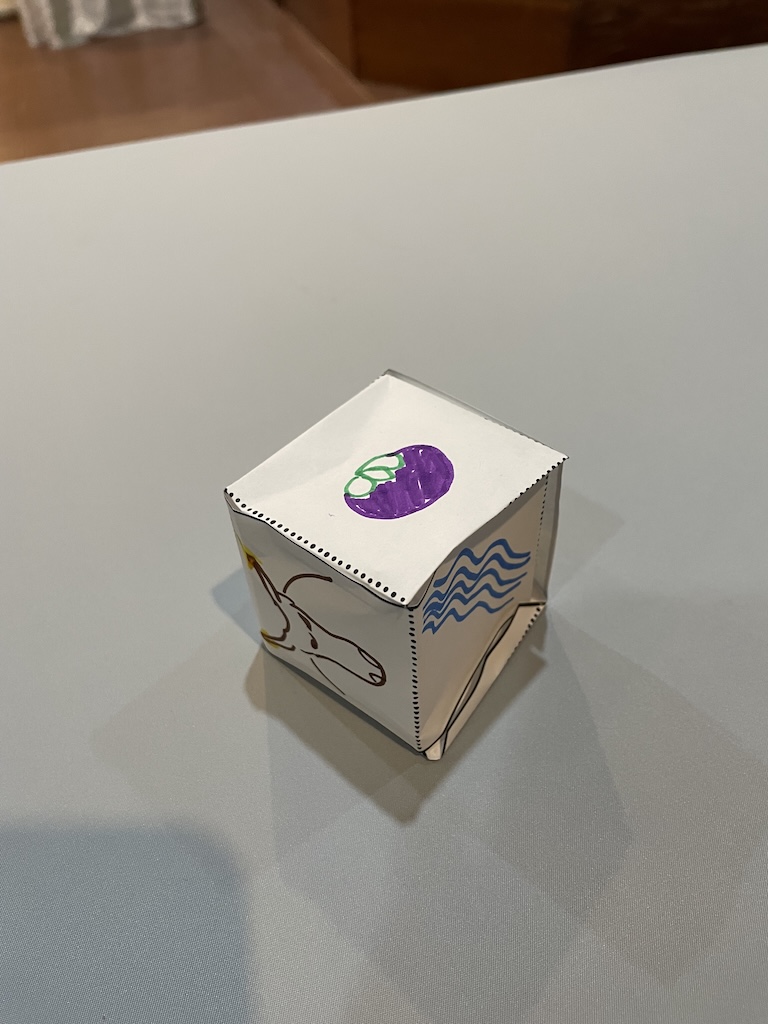

Taking these circumstances into account, the teachers and I explored ways to use translanguaging that were flexible and took few resources. We made our own story dice with printable paper patterns, tape, and markers. Teachers added simple pictures that showed objects from their many languages and cultures—soccer balls were popular, as were umbrellas (it was rainy season), ဖိနပ် [panaq], and tropical fruits such as မင်းကွတ်သီး. [man-kut-thee]They worked with small groups to play with their dice, using the images for collaborative multilingual storytelling.

For instance, one student might roll the die in Figure 2, see the water buffalo on top, and say, “One day there was a ควาย [kwai].” The second student rolls and gets the mangosteen on top, and continues the story: “The ควาย [kwai] was hungry and it saw a မင်းကွတ်သီး [man-kut-thee] tree.” The next student might continue, “The hungry ควาย [kwai] could not get the မင်းကွတ်သီး [man-kut-thee] down from the tree, so it walked to the river to drink water instead.” The story would continue with each new roll. Students could play with multiple dice depending on the size of the group.

Teachers had great ideas for how to use story dice in their own classrooms, including pre-making dice with a specific set of vocabulary (e.g., weather). They appreciated that the activity could work for groups with very different levels of English—some students might speak entirely in English, while others might use a few English words interspersed with other languages known by the group. All would learn at least a few English words, in a low-stress, low-stakes way.

One might fear that students would learn less English if they had the option of using other languages, or that the mixing of languages would confuse communication. Advocates of translanguaging would point out that languages are never “pure,” but always evolving and hybridized with loan-words. Teachers could decide which students they would push to stretch their English capabilities versus which ones they would welcome to simply participate in the activity in any language. As students advanced and matured, teachers could raise the bar for communication in the target language.

Zooming out from this small training I facilitated for English teachers, there is a larger picture to consider. Despite the painful history of language suppression in Myanmar, there have been positive developments for language rights in the last decade. Prior to the 2021 coup, Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE), in which children learn in their first language as they begin schooling, had been gaining prominence. In the Spring Revolution, the right to speak one’s own languages has been an important demand, to counteract forces of Burmanization as well as neocolonial dynamics that might pressure people to study English. Online universities such as Spring University Myanmar now offer classes in many ethnic languages. Many people recognize that multilingualism would be important in a federal democracy. This principle is reflected in the National Unity Consultative Council’s 2023 Federal Democratic Education Policy, which asserts the “linguistic human rights of all citizens,” meaning that “everyone in the Union has the right to speak, write, and develop their own language.”

MTB-MLE is educationally valuable, but it can be difficult to implement, especially in linguistically diverse classrooms, where teachers who speak each child’s language or the resources to train and hire them may not be available (Salem-Gervais et al., 2024). Therefore, mandating MTB-MLE in a future federal democratic union could create major challenges. While MTB-MLE is a rights-based model that asserts children’s prerogative to learn in their first language, translanguaging is a freedoms-based model that removes restrictions around language use. It’s not an either/or model with strict requirements, but a set of possibilities that teachers can explore as they are able. Schools that were able to implement MTB-MLE could do so or aspire toward that model, and those that couldn’t might use translanguaging strategies instead or in the meantime.

For instance, imagine a primary school in Karen state with mostly Karen and Burmese-speaking students, and some Karenni and Shan speakers. Under the military regime, only Burmese would be taught and tolerated, disadvantaging a majority of the students. In areas controlled by Karen EAOs, Karen might be the primary language of instruction, which would be a challenge for the kids speaking other languages. In the MTB-MLE model, teachers would need to be found for each of the four languages–nearly impossible in many villages. However, if translanguaging strategies were used, Burmese and Karen-speaking teachers might be able to meet the needs of the majority of students, while creating a welcoming environment where Karenni and Shan speakers were able to build on their language skills. Multi-age grouping could enable scarce resources to go further. When translanguaging is encouraged, teachers may find even more creative solutions to work around language difficulties.

The complexity of Myanmar’s language landscape can be daunting, but the creativity of its teachers is impressive. The most powerful part of the workshop I facilitated was seeing teachers’ willingness to keep developing in their profession despite significant obstacles. Several were actually learning new languages to communicate better with their students. They had so many insights and so much encouragement to offer each other. Their ingenuity and determination can be an example for educators around the world who are facing the challenge of how to serve students in linguistically diverse settings.

*I would like to thank Mary Shepard Wong, who facilitated this training with me, as well as to the staff of the community-based organization that hosted the training, and the teachers who participated.

Rosalie Metro has been working with teachers from Myanmar since 2001. She is an Associate Teaching Professor at the University of Missouri-Columbia.

Notes

Like This Article