Day Wi and Zoe Matthews explore the post-election approaches needed for political leaders to honour the trust of their constituents, from the perspective of education.

In the run up to Myanmar’s November 8th general election, there is an air of both anticipation and trepidation. Some voters see the election as a chance to express their grievances about or support of the NLD-led government’s performance so far. Some will be expecting the so far successful new mergers between ethnic parties in Chin, Kachin, Kayah, Kayin and Mon States to represent a push towards a non-territorial form of federalism in Myanmar in order to strive for ethnic equality and address ethnic grievances.

Also notable is the number of young faces representing the major ethnic parties, signaling the growing clout of the youth. This is important in that it represents the opening up of channels for youth from all backgrounds to air their grievances as the first generation to work in Myanmar’s slowly reforming economy. The current NLD government’s plans and activities may be out of touch with the needs and expectations of the young ethnic nationalities that had formerly placed their faith in them.

The growing disunity between the NLD and the major ethnic parties is a result of, in part, a reluctance to listen to the non-state education providers and youth civil society groups on the frontlines, who are dealing with the legacies of previous governing regimes. More consultation is needed with education stakeholders to promote a diverse and inclusive national education system and to ensure quality. This would allow future leaders better insight into the positive and negative impacts of education on peacebuilding processes and on balanced economic growth.

Starting from July 2012 and conducted over 3 and a half years, the Comprehensive Education Sector Review (CESR) provided an in-depth analysis of the status of education in Myanmar to identify realistic policy options and priority reforms, as part of the Ministry of Education’s (MoE) commitment to quality, inclusion and equity. The creation of the Joint Education Sector Working Group (JESWG) by the MoE facilitated coordination between the CESR Task Force (chaired by the Union Deputy Minister for Education) and Development Partners (DPs), such as the UN, multilateral, bilateral, non-governmental and civil society organisations. This led to the formulation of Phase 1 of the National Education Strategic Plan (NESP), which began in 2016 and ended in 2021. Included in the NESP is the diversification of education pathways, which would allow the government to tap into the potential of new generations in pursuit of ambitious socio-economic reforms, which have skills development as a core element.

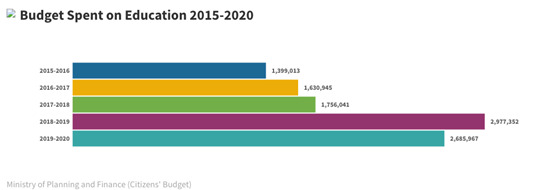

Over the 2015-2020 period, the MoE paid for items such as education infrastructure, scholarship programs for basic to higher education, and the overhaul of the basic education curriculum. This includes the development of the Local Curriculum with the support of UNICEF in five pilot states, which has been discussed at great length in another Tea Circle article. The production of local knowledge textbooks, by the MoE in collaboration with the local literature and culture committees (LCCs), is intended to teach the respective local histories, geographies and cultures of each state. This is an important step in both education and political reform, since the absence of ethnic languages has always been high on the list of grievances felt by ethnic nationalities.

Mother tongue-based education (MTBE) initiatives have also been important steps towards addressing the issue of language in education. Recognition that there is sometimes a need to use ethnic languages alongside Myanmar as a language of instruction can be found in article 43(b) of the National Education Law. Ongoing projects, continuing collaboration between the MoE and UNICEF in mother-tongue based education, include the production of ethnic readers and story books in different ethnic languages for primary schools. Ethnic parties such as the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy (SNLD) and the Mon Unity Party (MUP) have vowed to continue the promotion of such activities, as promised in their 2020 election manifestos. Their aim is to tackle unsolved issues that children in multi-ethnic minority areas are faced with in accessing education in their mother tongue at basic education level and to promote MTBE at higher education level.

In doing so, a good example of practices that should continue post-election is the empowering of local governments with policy-making autonomy in the process of decentralisation. According to the 4Rs framework (Redistribution, Recognition, Representation and Reconciliation), proposed by the education scholar Mieke Cardozo, redistribution of power in order to complete education initiatives like the Local Curriculum is necessary for education to become inclusive of all socio-economic groups and therefore contribute to Myanmar’s peacebuilding process. Doing so acknowledges the linkages between education, inequality, injustice and conflict and enables Myanmar’s challenges to be confronted with a holistic lens.

Other trade-offs in terms of language-in-education policy have included efforts to translate Burmese language materials, although these have been perceived as limited in effectiveness from a pedagogical standpoint. Non-state education providers, such as the Mon National Education Committee (MNEC), the Karen Education Department (now KECD) and other ethnic education providers, instead advocate for more collaboration in terms of deployment of teachers, creation of learning resources and joint education management and administration. If the new administration were to follow these recommendations, this would address all components of the 4R framework and signal a greater inclination towards collective decision-making between education providers.

The social dividends from this approach on peacebuilding processes would be enormous since the joint skillsets of all these groups in the provision of quality education directly correlates with the transformation of Myanmar’s long-standing conflicts. In order to help young people understand the root causes of the conflicts they are inheriting, education requires an open and culture-oriented approach emphasizing human rights and social justice. This asserts that state educators should invite non-state educators into the conversation about how to best address the learning needs of students, as specific to each context around Myanmar. Education policy-making then would be the result of a partnership between all education providers with the best interests of the child at the center of all initiatives.

Putting the needs and rights of the youth at the center of education initiatives would also mean directly confronting the current, real-world challenges faced by young people, in both rural and urban environments and in each of their unique contexts around Myanmar. While criticism of sex education, for example, may have been politically motivated, other opposition parties to the NLD need to heed the facts before they jump into the fray. Studies show that the provision of sex education programs does not lead to earlier sexual activity or riskier sexual behavior but in fact, reduces it. Teenage pregnancies, sexual and reproductive health issues, gender-based violence and homophobic bullying are all barriers to achieving good health and well-being. As the UNFPA, and colleagues demonstrate, the dangers of not providing comprehensive sexuality education are well-documented.

If election hopefuls take these warnings on board, it is also important for them to be aware that there is a direct link between context and effectiveness of comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) programs. The content of CSE programs must be appropriate to each culture in Myanmar and present an understanding that each of these cultures might convey different messages (whether positive or negative) regarding gender, sex and sexuality. The aforementioned ethnic party mergers may present an opportunity for that diversity to be respected in the review of the curriculum, if a similar process to that involved in developing the local curriculum was followed. Diversity in education leadership can ensure that dialogue processes are delegated to state and regional level, followed by the setting up of a review committee to collect input from actors such as the LCC’s, teachers and development partners, in order to ensure cultural relevance and sensitivity of CSE programming. Not doing so may inflame tensions and have a negative impact on peacebuilding processes.

Likewise, attention needs to be given to the decentralization of decision-making on environmental education. This is integral to the building of trust and understanding between ethnic groups and the sustainability of this achieved peace. Poor governance of natural resources has been linked to armed conflict in ethnic areas, yet land matters are being ignored by all parties in the 2020 elections. The urgency of reform in these areas is even more pressing given the increasingly visible effects of climate change. Teacher educators and student teachers at Education Colleges are now learning how to teach environmental geography and climate change themes at basic education level, but it will take time for young people to feel the agency that is needed to address this critical issue. Climate resilience requires a rapid and context-sensitive approach. Local and regional decision-makers need to be aware of the direct risks to the areas they govern and utilize education as a tool for climate response. The responsibility of climate response should also be placed on those in possession of key land areas. Committees in each state and region should plan for awareness raising programs to include even the most remote communities. Topics should center around the need for environmental protection and how each community can harness their local ecosystems, for example by planting forests to ensure the supply of clean water and reduce flooding. In this way, the climate resilience of ethnic states and the country as a whole would be stronger, since ownership and accountability would be shared between community level actors and all levels of government.

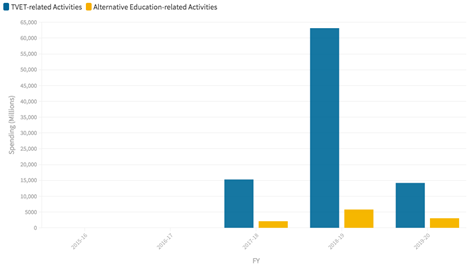

Of interest to the young candidates of the upcoming elections should be the amount invested so far on Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and Alternative Education. From 2017, spending on non-formal primary and middle education programs (alternative education) and vocational training infrastructure appears to be in line with what was promised by the NLD-led government in their 2015 election manifesto. According to the NESP, Phase 2 (2022–27) will aim to ‘successfully complete priority reforms’. The NLD’s 2020 Election Manifesto for the 3rd legislature indicates that this trajectory in spending on alternative and vocational training would continue under their leadership.

If the 2021-2026 legislature is really to make a difference in Myanmar’s transition, attention needs to be paid to this area in order to promote balanced and inclusive growth. According to the National Education Strategic Plan (NESP), an estimated 2.7 million learners (5-16 years) have either never enrolled in school or have dropped out of the formal education system. World Bank’s calculations are reflected in Myanmar’s OOSC data: for every 100 students entering primary education in low- and middle-income countries, just 35 complete upper secondary school. This leaves about a third of youth without the skills they need for further education or training, languishing in unstable, low-paid and low-productivity jobs that offer little career mobility or growth and further perpetuating the cycles of poverty and inequality.

Myanmar’s war-torn states demonstrate how conflict exacerbates this predicament. Low skills, few formal job opportunities and fear of recruitment by ethnic armed groups have been linked to an increase in the number of men—youth included—migrating from towns and villages to find work in remote, mountainous mining areas for example. Linkages have also been made between a lack of education and professional opportunities and an increase in crime. For example, motorbike theft in Mawlamyine and Ye has been on the rise as lack of jobs and under-education has driven gangs of youth to steal and sell bikes in order to subsidise their drug use. Interestingly, however, the election manifestos of the Tai-Leng Nationalities Development Party also known as the Shan-ni Nationalities Development Party (TNDP), and Karen National Party (KNP) do not mention a specific plan for education to address these issues. The Arakan National Party (ANP) vow to open more Education Colleges in Rakhine as well as provide postgraduate diploma courses at Sittwe University, as well as improved access to education in Rakhine State generally. Meanwhile, the SNLD pledge to develop vocational education and special policies for dealing with drugs and corruption through the medium of education, although it is unclear what these policies will be.

For election hopefuls planning on addressing education needs, the quality and relevance of TVET and alternative education programs to such contexts, as well as consideration of how to address low primary completion rates, are crucial for future policy-makers to successfully meet the needs of young people. TVET initiatives so far have been predominantly supply driven and lacking consultation with entrepreneurs, business associations and chambers of commerce. This has meant that training subjects have been defined with little or no consultation on the actual needs of the labour market.

Just as comprehensive sexuality education and environmental education should consider the diverse range of stakeholders on the ground, analyzing the feasibility and supply of possible TVET initiatives needs also to be a consultative process and coordinated at state and regional level. This would ensure a holistic approach to analysing the needs of a wide spectrum of young people, including those particularly marginalised because of their ethnicity, religion, socio-economic background etc., as demonstrated by one youth-led assessment in Rakhine state.

Lessons for ensuring quality and relevance of alternative education and TVET initiatives can be learnt from recent activities of UNICEF and UNODC. Their activities including social education campaigns were targeted in consultation with ethnic women and youth organisations. They also show that it is possible to replace criminal penalties with education and training for young drug addicts or those at risk, while at the same time stemming the production of opium in the northern states through alternative development.

Other lessons have been presented in the form of Youth Information Corners (YICs) in contribution towards the Ministry of Health and Sports “National Strategic Plan for Young People’s Health”. YICs have been identified as key to ensuring that the sexual and reproductive health of all young people are protected in times of disaster. Education policy-making therefore also needs to be gender-responsive. Education planning for women should consider the distances that confront women and girls and their security, as well as traditional gendered expectations for women in reference to their roles within the home. UNESCO recommends that curriculum reforms present an opportunity also to challenge gender norms since targeting all the youth defines the future health and resilience of their communities.

Caveats for future policy-makers in ensuring quality and relevance of education

There are incentives for more collaborative and consultative approaches by the 2021-2026 administration to providing out of school children with ‘second chance programs’ like alternative education and TVET. With each additional year of schooling and upskilling, an individual’s earnings is raised by 8–10 percent, especially for women. Increased employability is commensurate with increased economic investment and growth. However, evaluating the government’s performance only on monetary investments and student enrollment rates, would be a disservice to the young people education reforms are intended to benefit. We need to be aware that ability and talent is the result of additional investment in time and socio-cultural capital. Economists looking only at investment or overall profit fail to take into account the fact that how much a young person profits depends on whether they are able to thrive in society.

In other words, our education system needs to give young people the ability to make connections to other people and to establish a network of social connections, which they can leverage to secure material or symbolic profits in and out of the workplace. So far, the inclusion of “Life Skills” and “Morality and Civics” as subjects in the new Basic Education curriculum are important steps towards the accumulation of socio-cultural capital by students. These represent a focus on promoting sustainable development competencies and 21st century skills. Through these subjects, young people learn to co-exist peacefully and productively with others, and the skills for participating in an increasingly competitive and talented labour force.

Herein lies an additional caveat. Recent Basic Education reforms may be perceived as reaching the targets laid out by the NESP in increasing student and teacher numbers. However, the evaluation of education institutions needs to extend further than whether they adhere to MoE policies and regulations. They should also include teacher and school inspection systems in order to evaluate learning outcomes and teaching/administration quality. Time will be needed, of course, for quality assurance systems to become robust and reliable indicators for future strategy-making for the Basic Education system, let alone in the establishment of skills standards, certification development and monitoring and evaluation systems for TVET.

Finally, future leaders should pay attention to the challenges faced during recent collaborations with civil society. For example, the NLD-led government has made headway in collaboration with the National Youth Congress in developing a National Youth Policy for Myanmar. However, sustained partnerships between decision-makers and the youth have so far proven difficult as per reports by Search for Common Ground and Paungsie Facility. Such challenges can be translated into opportunities for future governments, for example by ensuring that there is enough funding and time set aside for meaningful and inclusive processes of dialogue.

Visions for the future

A growing expanse of literature, including policy papers, on the dividends of consultation with stakeholders in education reform is now available to the 3rd legislature of policy-makers. Both the NLD and the major ethnic parties can use this as an opportunity to instigate meaningful change in Myanmar and stamp out the prevailing ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality once and for all. But this is only if this call for dialogue and accountability is addressed. Committees need to be assembled in the education policy-making process, gathering diverse actors, which together form a credible body to assess the wide range of complex and contentious issues presented in this article. Successive governments need to pay attention to creating monitoring and evaluation systems that measure the performance of the education system both in terms of economic and equity outcomes. This would ensure that all young people growing up in today’s Myanmar, including those currently unreached, have a way to accumulate socio-cultural capital and assist the country in meeting all eight of the Millennium Development Goals.

Day Wi (Hnin Wutyi Aye) is a researcher working in education research with Yangon-based think-thank Urbanize: Policy Institute for Urban and Regional Planning. She completed her Bachelor’s degree in Education and Psychology at Asia-Pacific International University, Thailand.

Zoe Matthews is an independent education consultant based in Myanmar. Her research interests include learner social identity and the intersection between education and peacebuilding. She co-founded a not-for-profit organization in Myanmar called Mote Oo Education in 2013.

The authors wish to thank the Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS) for its support to this research project.

Like This Article