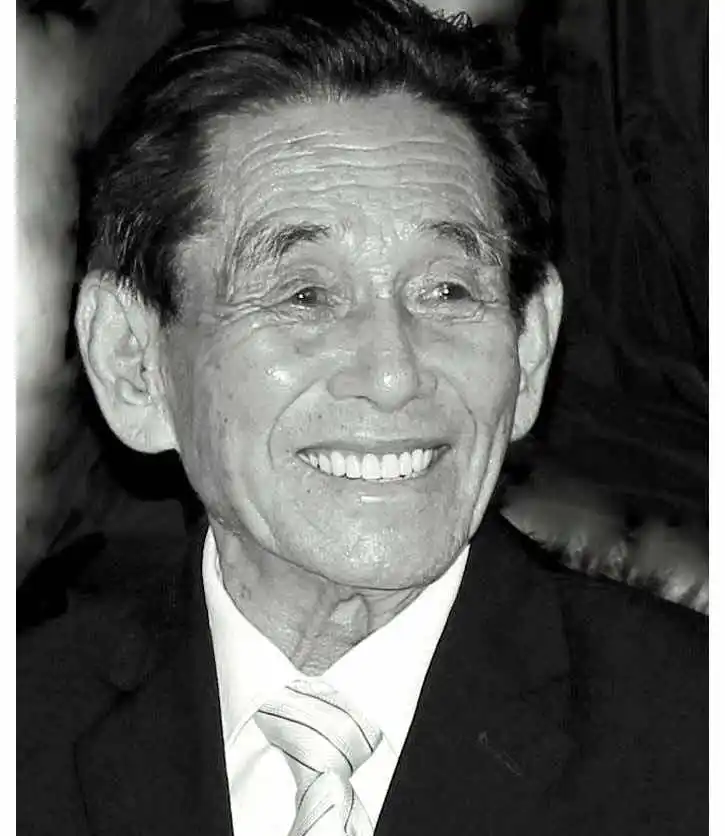

Liu Yun looks at an influential figure in the peace process.

He may be an octogenarian, but Peng Jiasheng (born on 26th January, 1932) is still active and playing a critical role in Myanmar’s Peace Process, to which State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi has attached the highest priority. Under his leadership, either directly or indirectly, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) has become the bitterest enemy of the Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces), whose Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing rose to prominence in 2009 for leading a successful offensive against Peng Jiasheng in the Kokang region of Northern Shan State.

Before that offensive of the so-called “88 incident” resulting in his “fall from grace”, Peng himself summed up his legendary life experience in a March 2009 document entitled “Self-narration by Peng Jiasheng” as consisting of “eight rises and seven falls”. Recently he said in a relaxed tone in an interview, “for the time being I am in the midst of the eighth fall”. Peng Jiasheng holds the view that the “88 incident” was not just his personal failure, but more miserably, an ethnic disaster for the minority Kokang people (Mandarin-speaking Han Chinese living in Kokang) who since then have totally lost the rights of ethnic autonomy in Myanmar.

According to my count, five of Peng’s “eight falls” were linked with the Myanmar central government’s efforts to “pacify Kokang”, while four of his “eight rises” were related to Kokangese armed rebellions against the Tatmadaw. With a lifetime effort, Peng Jiasheng devoted himself to the regional ethnic affairs of the Kokang. In 1989, he became the first communist-turned-ethnic leader to come to a ceasefire deal with the government troops, thus designating Kokang as “Shan State Special Region 1”. It is noteworthy that Peng did not include this dramatic change, by which he led a mutiny within the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) and became a darling of the then-military government, in the list of his major “eight rises”. Neither did the MNDAA’s 2015 offensive into Kokang enable Peng Jiasheng to rise again in his home territory.

Currently, the MNDAA is one of the 7 founding members of a newly formed ethnic political alliance, the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC). This group is led by the 30,000-strong United Wa State Army (UWSA) and has the self-described aim of “discussing with the government of Union of Myanmar regarding the issues of peace-building in Myanmar”. Peng Jiasheng is probably the most enthusiastic advocate of uniting all Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs). From his point of view, the lack of genuine unity is the primary problem for EAOs in building long-term peace with the central government. Within the FPNCC, there is a more closely tied, hard line group, self branded as the “Northern Alliance” (NA) comprising the MNDAA, the Arakan Army (AA), the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA). I discussed the offensive tactics of the NA in an earlier piece on Tea Circle. As a matter of fact, the senior KIO official Sumlut Gun Maw pointed out that only two KIA brigades had participated as members of the NA. Consequently, it is believed that the MNDAA’s increasingly critical, if not dominant, influence in the NA has been reshaping the landscape of security and ethnic politics in the borderland.

A lot of times, ethnic issues in the borderlands are interpreted through either grand narratives of the modern China-Myanmar relationship (mostly about China’s leverage over Myanmar) or power struggles among “warlords” and big families. There is actually a strikingly long history of co-ethnic groups residing on both sides of the China-Myanmar border. Those groups, from ancient times to the present, must have had a hand in the contemporary politics of both countries for their own sake. I will elaborate thoroughly in a future article that the borderland ethnic politics could be dated back to as early as the 13th century when Kublai Khan launched a campaign (from 1277-1287) against the then-Pagan kingdom. This occurred after Yunnan submitted to the jurisdiction of Beijing, which coincidentally has become the capital of consecutive centralized empires and republic.

Now in Myanmar, as argued by Thant Myint-U, “a resurgent nationalism is taking shape but remains inchoate, uncertain of its attitudes toward the country’s many and varied minorities, relations with the West and China, as well as the very idea of Myanmar democracy”. As a possible response to this new dynamics of nationalism, one scenario could be that Peng Jiasheng’s philosophy of struggle against “Burmese chauvinism” is going to win more popularity across the border, with he himself becoming an ethnic icon of struggle and survival.

Liu Yun is an independent analyst based in China. He writes on Myanmar regularly. He can be reached at: liuyun5398@hotmail.com

Like This Article

September 26, 2024

September 11, 2024