Alex Aung Khant on navigating the media.

Fake news.

Since Donald Trump’s rise to the presidency in the past year, this phrase has been associated with bigotry and complete denial of the reality of the situation, and the refusal of Mr. Trump’s administration to face facts, whether it be on issues of climate change, or on racial violence in America. This is not to say that fake news does not exist. We all know of viral hoaxes that circulate on our social media news feeds, everything from fake celebrity deaths to political atrocity propaganda that are calculated for maximum clickbait attention, all trying to tap into our most sensitive heartstrings to bring out what has been dubbed “keyboard activists.”

In a world of Instagram filters and snapchat stories, our attention to tread through the finer details of critical issues is arguably at an all-time low. News coverage of today’s events rarely makes it to tomorrow, let alone the week after. This shortened attention span also brings us to a common fallacy of forgetting our due diligence to examine the evidence put forward properly, before spreading what would otherwise be misinformation. And with the technology so readily available to alter images and distort reality, Photoshop is often unrecognisable from truth. This, of course, takes advantage of our natural reluctance to take the extra step in fact-checking what we see and hear.

Meanwhile, with the internet and social media platforms, our ability to shout out in protest is just a passive click away. To the publishers and content creators, any attention is good attention, because more site views means more advertisement money. This internet economy is significant enough that publishers and content creators are now more than ever fuelled by the need to be first, rather than the need to be true. Being the first to post, publish and ultimately sell hot topics, is the name of the game today, rather than detailed and nuanced analysis that is fundamental to good journalism. The reality of this scenario has already written the plot for films like Spotlight and Nightcrawler.

Even NGOs and personalities have now joined the fray for online attention, releasing official statements and tweets alike. With social media giving them a far wider reach than ever before, it is a slippery slope when their statements are not based upon their own proper research or experience but rather echoing what other media outlets have already released. It might even be the case that the original evidence was only put forward by one media source, and circulated over and over, without proper fact-checking. By resonating with other sources on a popular topic, not only does it make it easy for content creators to simply copy paste and rephrase the content, it also lessens the need for spending time, energy and money on actual investigation. The potential online revenue created by the media hype is also an incentive for content creators to get their share of the pie while the buzz lasts.

The latest media focus on Burma has been on the humanitarian crisis in Rakhine state. The majority of foreign media reports have stood in plain condemnation of the new government for its failures in Rakhine state, while the majority of local readers inside the country have criticised foreign media for one-sided stories and lack of nuance. In order to see the contrasting viewpoints on this issue, it is important to first unravel the background context of the Burmese audience to get a fuller picture.

Coming out from years of closed military oppression and isolation from the world, much of Burma’s population is actually more familiar with passing along news via word-of-mouth, than reading the news themselves. Part of this habit is because the few local news agencies that operated inside the country were completely controlled by the regime, and what was allowed to be printed was heavily censored and altered in their favour. I myself have experienced this firsthand during my days as a young trainee at The Myanmar Times.

The only source of reliable news back then was thus foreign news. Under the military regime, it was extremely difficult for local news from inside the country to be sent abroad, yet foreign news broadcasts were easily accessible through various radio broadcast channels. Foreign countries thus had far less knowledge of the troubles brewing inside Burma, yet we in Burma knew most of what was going on in the rest of the world.

Satellite TV news, often pirated from China and Thailand via the giant satellite dishes that litter the rooftops of major cities, would also provide a glimpse of the outside world. It is even proposed in some circles, that the video clips of American fighter jets taking off from aircraft carriers, and the aerial bombardment during the Iraq War, was what influenced the Burmese generals to move the capital further inland to Naypyidaw.

Burma had long been a country hungry for news, and this national appetite has now moved to online platforms. This stands in stark contrast to what was the status quo ten years ago, when internet connection inside the country was pitifully slow, and the only SIM cards that were sold by the regime-backed MPT provider cost US$1500. (Yes, that number is correct, and you had to sign up on a waiting list before receiving one). Now, fiber optic connections and 4G connectivity is increasingly available especially in Yangon, and a SIM card can be bought at any corner store for less than US$1.50. In 2014, it was reported that only 7% (about 4 million) of the country had phones. In just three years that number has exploded exponentially. June of this year, The Myanmar Computer Federation reported about 90% of the country had access to a smartphone with internet service.

The move for mobile-centered engagement is most visible in the way government authorities now communicate with the public. High-level public offices now all have dedicated official social media channels for communicating news to the public, and private companies have also followed suit to gather a following. Even regional parliamentary meetings are posted online.

Burma has essentially made a digital leap forward in telecommunications, but the consequences remain yet to be examined. This is especially problematic for a country where the digital literacy and online-awareness has lagged behind substantially. These shortcomings have big impacts on the people’s interaction with online media. For people finding themselves suddenly with a smartphone in hand, it can become a black-and-white decision to either believe completely in whatever they may see online, or conversely to completely reject it all together. This can divide the population on any given issue into believers and nonbelievers, with little nuance in-between as there are still very few with the capacity to tread carefully through the overwhelming, often one-sided news sources. Given Burma’s context of a troubled path since independence, uniqueness as a previously isolated dictatorship finding its own way towards a peaceful democracy, as well as the complex ethno-religious ties, amongst various other elements, giving a justifiable, nuanced news report on Burma is not an easy task.

There are also other, more pragmatic shortcomings that exist in less-obvious forms. For example, telecom providers in the country have set up “Free mode” incentives for Facebook – a boiled-down, mobile-version with only the bare-bone features, that does not consume any data. Basic headlines and comments are included, but users have to pay data charges to see pictures and to follow the full details of articles. It is a great incentive by all means, but it is often forgotten in the larger political context that users end up only interacting with the hard-hitting headlines and strong-worded opinions in the comments. When complex issues are reduced to just blurbs, the nuance and details are out the window. Issues like this may be a small road-bump, but a bump nonetheless in a country with very little internet literacy.

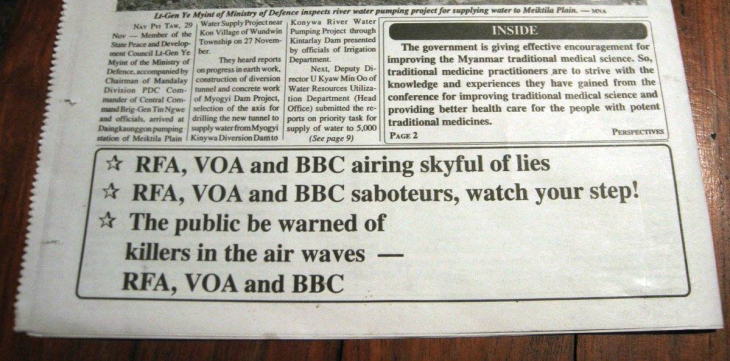

All these factors combined have contributed to the recent turn of public opinion against many foreign news outlets and reporters. Only a decade ago, the military regime’s propaganda machine printed out daily newspapers with slogans that painted foreign media as “airing skyful of lies – saboteurs, watch your step!”. Today, these words now resonate with people inside the country in criticism of foreign media. Ten years ago, the entire country relied upon feeble radio broadcasts from RFA, VOA, DVB and BBC for reliable information, and now these same sources are seen in the opposite light. (It is also worth mentioning here that the same news clips of the Iraq war, that once made the generals fear a US attack and influenced their move to Naypyidaw, may have coagulated over the years and are perhaps one of the pivotal reasons why the local population have a poor image of the Islamic world. These clips may have played a pivotal role in changing local views by associating Islam with stereotypes of radical violence, stereotypes that are now present in many other parts of the world).

The focal point of this local disdain for foreign news, comes mainly from the criticism coming from foreign media, and secondly from the lack of nuance of the ongoing Rakhine crisis in the border region with Bangladesh. Like most of the border conflicts in Burma, the Rakhine conflict dates back to pre-colonial times, and the beginnings of today’s flames can easily be traced back to the colonial method of drawing maps and the divide and rule of fluid communities through states and citizenship.

The simpler way to say this is that it is immensely complex. The Rakhine problem goes back through our murky history and involves multiple layers of depth, with several different actors and stakeholders involved. It is also centred around an understudied region that is home to two large communities. Small mishaps like incorrect translations further add to the problem. These reasons and as well as the aforementioned context of Burma, are just some of the nuances that could add much further depth and understanding of the crisis, but have yet to be addressed at length by foreign press and media.

Readers inside the country are fully aware of the country’s precarious political balance, and do not feel that the media does justice by singling out the affected Muslims, and conveniently leaving out the other affected communities. Even if the sheer numbers may not be comparable, it is nonetheless an important element to add the multiple angles of any story, unless it is either professionally incomplete, or intentionally scrubbed off. These uncertainties only add to the local disapproval.

There is no doubt that the current crisis is a grave humanitarian issue, and those responsible should be held accountable. But for any complex crisis to be boiled down into incomplete and one-sided news blurbs without consequences is of course unthinkable, yet this is what has gone on in much of the global media lately.

In the same way that pockets of radical terrorism have been used by the media to tarnish all of Islam, one individual extremist monk has also been singled out by the media to tarnish all of Burmese Buddhism. If the Rakhine crisis is to be continuously pitted solely as one particular issue of either ethnicity and identity, or religion, or the failures of the current government, it would amount to cherry-picking and could potentially undo the efforts of Burma’s democratic struggle. Instead of just cherry-picking facts and pointing the blame, the media could potentially unlock the reasons why this conflict ever even started in the first place, why it remains unsolved and what it will take for all parties to reach a fruitful resolution.

Journalists have a professional duty to show the truth, but they also have a corporate duty to sell that truth. Sometimes, bad news is indeed good news, for without conflict there would be little to write about. Truly good news rarely makes headlines, and for there to be wider national reconciliation and peace in Burma, the best news would then be to have no news.

Harold Lasswell, renowned political scientist, wrote that “every war must appear to be a war of defense against a menacing, murderous aggressor.” In the name of defending state security, peace, religion, or even human rights, spreading fake news and propaganda plays on our human nature of judgement and abidance to ethics by claiming to be noble defenders of these concepts, while painting the other as the aggressive wrongdoer. It is the base of political propaganda that allows those in power to make decisions at the expensive of other lives.

We as global citizens should remind ourselves to tread carefully before taking up sides, and to be careful not to fall to whichever side the media, and second-hand perspectives often lead us to. As the saying goes “if you don’t read the news, you are uninformed. If you do read the news, you are probably misinformed.”

Alex Aung Khant is Executive Director at Urbanize, a local policy institute for urban and regional planning. Alex is from Yangon, Myanmar, and holds a Masters degree in Urban Studies and Public Policy from Sciences Po in Paris, France. He obtained his B.A. in Political Science and Asian Studies, also from Sciences Po Paris.

Like This Article

April 09, 2024

February 23, 2024

December 02, 2021