Greg Constantine shares stories about Rohingya educational achievement in Myanmar, from the photo project Ek Khaale, which documents Rohingya belonging in Myanmar.

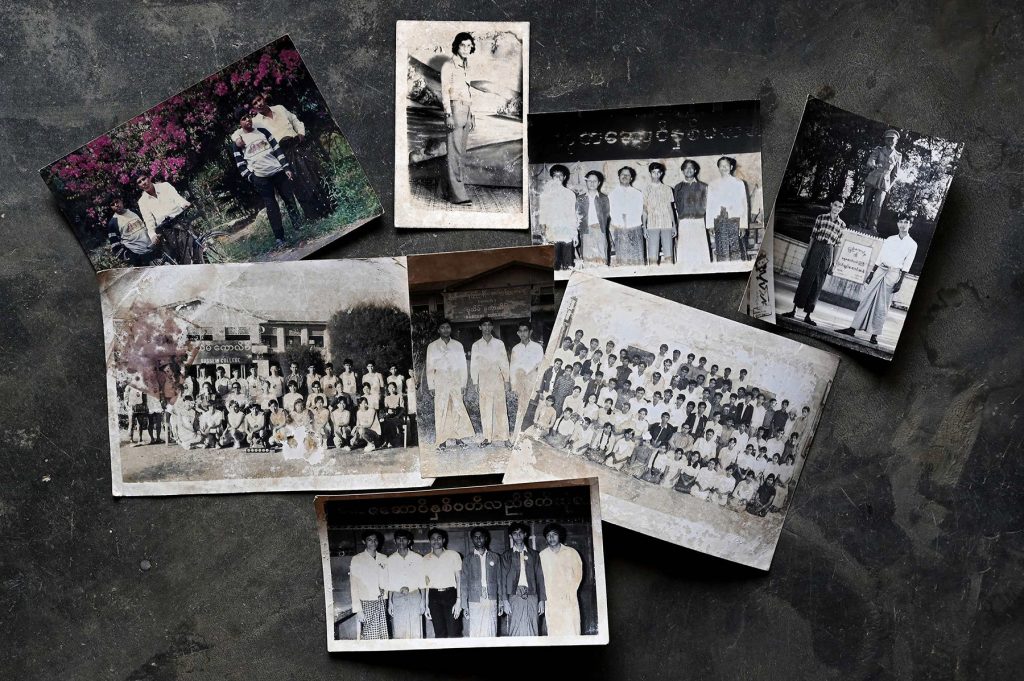

Mohammed places document after document down on a mat on the floor of his hut in the refugee camps in southern Bangladesh. Student ID cards. A graduation certificate. A graduation ceremony program. Color photographs of him in a black cap and graduation gown standing proudly with his peers. Young adults from the Shan, Kachin, Bamar, Chin, Mon, Rakhine and other ethnic communities throughout Myanmar have similar photographs. These documents attest to a historical moment experienced by young men and women everywhere. Mohammed was the first in his family to graduate from university. Mohammed was also the last in his family to graduate from university. He is Rohingya.

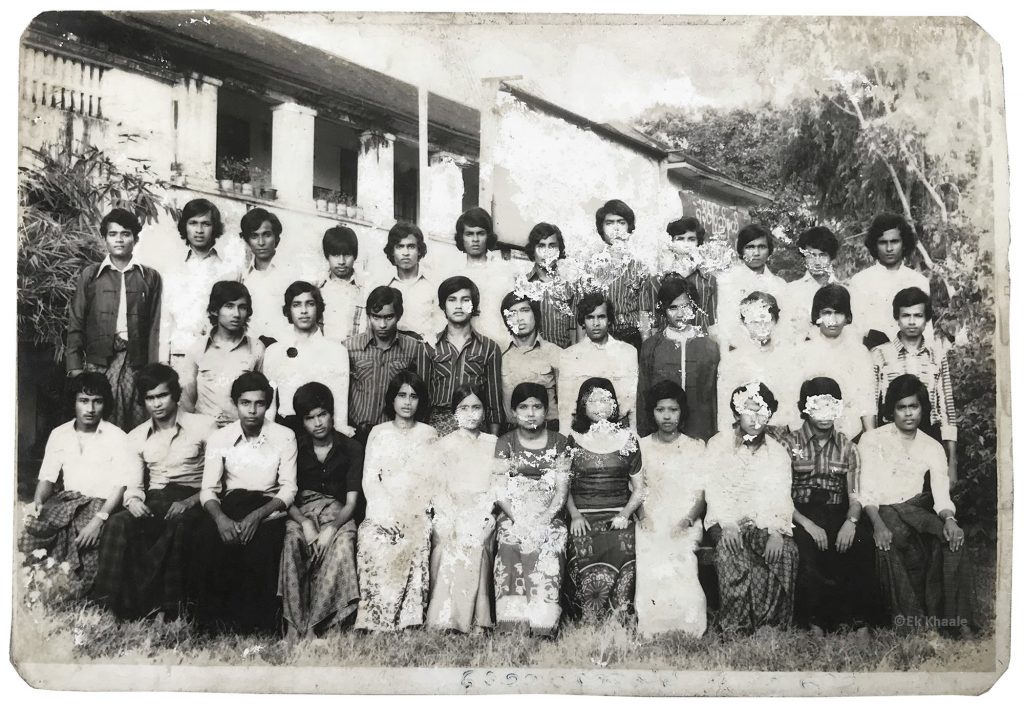

For many decades, Burma had one of the best education systems in Southeast Asia, including some of the most prestigious universities in the region. Rohingya contributed to the development of the national educational curriculum during the 1920s and helped develop some of the first private high schools in Rakhine State. They were influential and respected teachers, headmasters and administrators. As students, Rohingya attended Burma’s top universities and technical colleges with peers from other ethnic communities throughout the country, especially from the 1950s to the 1980s.

When government discrimination and restrictions on travel intensified toward the Rohingya, it became increasingly difficult for them to study in Yangon. Rohingya students continued to pursue degrees at Sittwe University in the provincial capitol of Rakhine State. Yet, after the violence in Rakhine State in 2012, the government banned Rohingya from access to higher education. For the next ten years, until May 2022, Rohingya youth were not permitted to attend Sittwe University. The academic futures for at least one Rohingya generation, and possibly more, evaporated.

Today, nearly all visual representations of the Rohingya portray a people defined by displacement, violence, otherness, persecution and victimhood. Successive regimes as well as prominent figures in Myanmar and others have rejected the Rohingya community as belonging to Myanmar. This narrative rejecting the belonging and recognition of the Rohingya has been widely accepted by the public in Myanmar.

Five decades of forced migration and displacement in addition to the physical destruction of documentary heritage has dismantled long-established ways in which the Rohingya preserve, share and endorse cultural memory and identity among themselves and with others. It has also limited their ability to confidently, collectively and effectively contest the claims of foreignness and visual representations that have been imposed upon them.

Ek Khaale is the expression “Once Upon A Time” in the Rohingya language. This is a collaborative, co-participatory project with Rohingya in several different countries, including: the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Ireland, Malaysia, Germany, Denmark and Australia, as well as Rohingya living in Bangladesh and Rohingya still living inside North Rakhine State. The project started in 2021 and over the past three years, Rohingya have contributed old family photographs, group photographs, ID cards, land documents, letters and other visual forms of documentary heritage to the project. Ek Khaale is divided into sequential and thematic chapters that deal with different periods and topics in Myanmar’s history, highlighting Rohingya’s place in that history. Chapter 8 focuses on education.

One of many gifts an archive provides is that it awakens the past and places it in the present. And in so many ways, what people see in an archive has the ability to re-establish a history that has been forgotten, or to correct and re-align a history that has been falsified and accepted by the majority as being true.

What Rohingya did in the 1950s, 60s, 70s or 80s might have been decades ago, but these visual moments have a place in a trajectory of a historical timeline that are linked together, build upon each other and when sewn together, they bring us to now. For people in Myanmar, a significant part of the Rohingya community’s historical timeline has been, for the most part, questioned, denied or just erased.

All of the materials in the project Ek Khaale synthesize together, collectively in a process that is a restoration, is a rewinding of the visual representation of the Rohingya most people have of this community, including those who live in Myanmar, people who live around the world and also people within the Rohingya community itself.

This chapter in the project Ek Khaale, awakens rare and never-before-seen photographs of graduation ceremonies, university clubs, student unions, teacher and student trainings, yearbooks as well as other documents, to show how Rohingya were deeply engaged alongside peers and colleagues from other communities in the academic life of Burma over the decades.

It shares a visual representation that many have never seen before: a representation of the Rohingya and their history that the Burmese authorities have done everything in their power to destroy and erase.

Greg Constantine is an independent documentary photojournalist, author and researcher. He has spent over 20 years working on long-term global projects that focus on human rights, inequality, discrimination, genocide and the power of the state, the projects Exiled To Nowhere: Burma’s Rohingya, and Burma’s Path to Genocide.